The man behind the incredible images in NATURE’s Under Antarctic Ice is Norbert Wu, an independent photographer and filmmaker who has photographed in nearly every conceivable locale, ranging from the freezing waters of the Arctic and Antarctic to the coral reefs and jungles of the tropics. Wu’s work has appeared in thousands of books and films, and been shown in museums. He holds electrical and mechanical engineering degrees from Stanford University, and did doctoral work at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

In 1997, 1999, and 2000, the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) awarded Wu Artists and Writers grants to document wildlife and research in Antarctica — journeys that ultimately resulted in “Under Antarctic Ice.” In 2000, he was awarded the U.S. Antarctica Service Medal “for his contributions to exploration and science.”

NATURE recently touched based with Wu at his studio near Monterey, CA.

You’ve photographed and filmed all over the world — what made you pursue such an ambitious project in Antarctica?

The man behind the incredible images in NATURE’s “Under Antarctic Ice” is Norbert Wu, an independent photographer and filmmaker who has photographed in nearly every conceivable locale, ranging from the freezing waters of the Arctic and Antarctic to the coral reefs and jungles of the tropics. Wu’s work has appeared in thousands of books and films, and been shown in museums. He holds electrical and mechanical engineering degrees from Stanford University, and did doctoral work at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

In 1997, 1999, and 2000, the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) awarded Wu Artists and Writers grants to document wildlife and research in Antarctica — journeys that ultimately resulted in “Under Antarctic Ice.” In 2000, he was awarded the U.S. Antarctica Service Medal “for his contributions to exploration and science.”

NATURE recently touched based with Wu at his studio near Monterey, CA.

You’ve photographed and filmed all over the world — what made you pursue such an ambitious project in Antarctica?

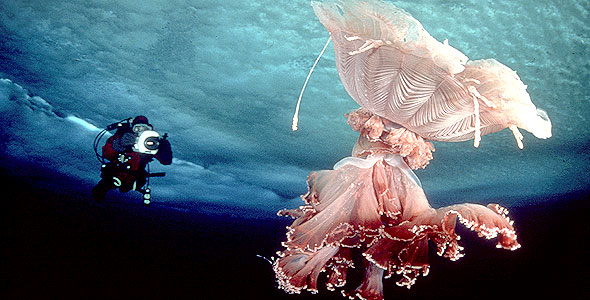

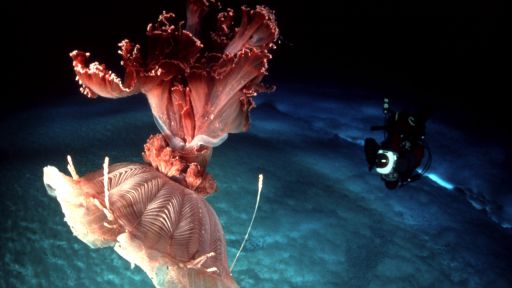

In 1997, I first went down to McMurdo Station in the Ross Sea, the southernmost marine environment in the world, to shoot still photographs. Scientists had thought that Antarctica’s water, like the Arctic’s, supported little diversity of life. But the southern seas are proving to be full of surprises. While the topside life is minimal, the marine life is dynamic, colorful, and extensive. I shot 500 rolls of film, and those photos proved to be tremendously popular. My experience led me to propose a documentary on Antarctica’s marine world to Nature. Fred Kaufman, NATURE’s executive producer, asked me to shoot the documentary in high definition (HD) video, so viewers could “truly experience the otherworldliness of Antarctica.” So I returned to McMurdo in 1999 and 2000 with a film team.

Isn’t Antarctic diving dangerous?

Diving in freezing water — water temperatures were 28.8 degrees Fahrenheit — can be tricky. But its not as harsh on the gear as you might think. There were days where we had topside conditions of negative 40 degrees Fahrenheit and the saliva in my mask immediately turned to ice (you spit in the mask before diving to prevent fogging during the dive). My drysuit froze up so I could barely move. But since water can only get so cold before it freezes, the underwater environment is relatively warm and at least predictable.

As a teammate, Dr. Dale Stokes, once put it: “There’s this large, active, colorful community under the ice, and then you come up through a hole into a raging blizzard.” We did have a few problems with the gear, but none of them substantial. Also, diving from sea ice was heaven for me, since I detest boats. Sometimes doing a dive was as simple as loading one of our tracked vehicles, driving to a heated hut over a hole in the ice, and jumping in the water.

Was Antarctica the toughest place you’ve ever worked?

I wouldn’t say the toughest. Typically, when people hear we are diving in ice, they can’t believe it. But in Antarctica you have a base and lots of support. The dive huts protect you from the cold, and at the end of the day, you usually have a warm bed and a meal. Tropical locations often present more problems. You’ve got humidity and insects. Every environment has its own set of obstacles.

It took you two years to shoot the film. Why?

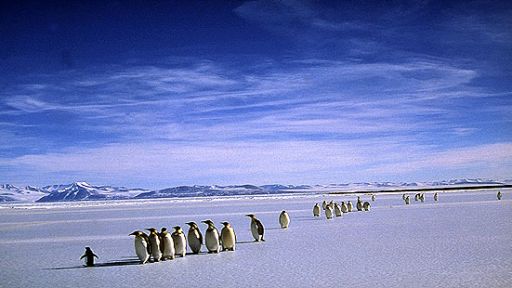

If I had done this film in only one season, we might not have seen certain things. There are some sights that don’t change much from year to year, but some do. You might not be able to get out to the ice edge to see orcas, for instance, or find a grounded iceberg. If we’d had only one year, we wouldn’t have gotten any penguin diving sequences. Also, because of limitations down there you can only spend 45 minutes under water before you get out. So you can’t spend hours in the water to film animal behavior. Then, there’s the weather. You have to be prepared to change your plans at a moment’s notice. So you need time and a backup plan.

What made you choose the HDTV format?

Natural history filmmakers like myself are excited about HDTV technology because it has a lot of advantages over film. My biggest problem as an underwater filmmaker has always been the size of the film loads. A typical film load generally lasts for only 12 minutes, which means that I often have to cut short my dives to reload film. But I’m able to shoot 40 minutes per dive with HD cameras. There are other advantages, too. I was able to use zoom lenses, despite the low light levels under the ice. The HD cameras pick up this very dark environment well. “Under Antarctic Ice” represents, to my knowledge, the first time that HDTV technology has been used underwater in Antarctica.

Does the technology have any downsides?

Well, one problem with HD is that your equipment has to be super clean. Any speck of dust or snow has a major effect on the image. We had penguins jumping up in front of us splashing water on the lens, and even the tiniest particles would appear in the picture. With film, particles on the lenses are far less of a problem.

Are you ready to return to Antarctica?

It’s an amazing place, and there are always new places to see. It really is the world’s last wilderness. Everyone who has been down there never forgets the experience. But it’s always nice to leave too.