TRANSCRIPT

[gentle music] - [Narrator] Antarctica.

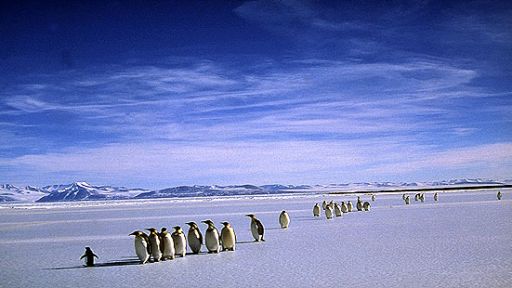

A familiar world of ice and penguins.

But travel a little farther, and the familiar falls away.

Beneath the shield of ice are new worlds to explore.

Underwater photographer Norbert Wu and his team Dale Stokes and Christian McDonald have traveled to the ice to get under it.

To discover the mystery and the beauty of life under Antarctic ice.

[gentle music] [adventurous music] [animals roaring] [man vocalizing] - [Announcer] This program was made possible by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

[wind whistling] - Welcome to Christchurch.

Welcome to the CDC.

Welcome to a new, exciting, new season, hopefully.

Okay, the first thing, of course, to remember is the clothing we've packed in your orange bags for you today is based on where you're working in Antarctica and what particular job you're doing.

And of course, what we're going to do this afternoon is to get you to try your ACW gear on before we send you south tomorrow.

Okay.

- [Narrator] They call it going to the ice.

It's a simple thing to say, but the journey is profound.

Tonight they'll get warm clothes in this United States National Science Foundation warehouse in New Zealand.

Tomorrow, they'll leave for Antarctica, 2400 miles to the south.

- [Norbert] My name is Norbert Wu.

I'm an underwater photographer.

I've been going to the ice since 1997.

Most people call me Norb.

- [indistinct] too tight.

Turn them back in, just getting the paints.

- Okay.

- Just the books.

- Yeah.

- Well known for Antarctic photography, Norb Wu and his team have been invited by the NSF's Antarctic Program to take high definition video cameras into some of the least accessible waters in the world.

- Norb apparently got a phone call this morning.

My name is Christian McDonald.

I've been to the ice six times.

I'll be diving and helping Norb with logistics.

How much weight, what are our allocations?

- Weight, actually.

- Okay.

- And at this stage it's 280 pound, unfortunately, which means that we can only take so much of your gear.

- Okay.

- But it'll follow.

- [Christian] It'll follow the next flight.

- [Woman] As soon as possible here.

- What's going on and all?

- Well, we gotta repack everything.

So this stuff is gonna join us on the next flight, which could be anywhere from just two days to two weeks.

Never know.

- Check in time tomorrow morning will be five a.m., okay?

So that's basically all there is to it.

- At first, it's like getting up early to go on an airline or to anywhere.

Same standing around, same security hassles.

Feels like going to Chicago.

[woman talking indistinctly] Hey Dale, can you do me a favor and hand me my parka?

It's right over there.

- [Dale] This is the second year I've gone to the ice with Norb.

I'm Dale Stokes, I'm an oceanographer.

- [Narrator] This is no airliner.

This is not a trip to Chicago.

It's so no noisy in here, you can't talk.

You can barely move.

It will be an extremely uncomfortable five hour journey.

About all anyone can do is think about the ice.

[gentle music] Antarctica is dominated by ice.

Over much of the continent, the ice is more than one and a half miles thick.

This fortress of cold holds captive 70% of all the fresh water on the planet.

If the ice melted, the oceans would flood over half the world's population.

The ice controls the Earth's climate.

It reflects heat from the sun back into space.

The sea water it chills affects currents and temperatures everywhere.

But there is more to Antarctica than just ice.

On the surface, Antarctica seems bleak, with its endless cold and its flightless, awkward birds.

But that's only on the surface.

Norb, Christian, and Dale are going to the ice to get under it.

[mysterious music] Norb's team is flying as far south as you can go and still find ocean.

This is less than 900 miles from the South Pole.

It's even too far south for most penguins.

Out of 17 penguin species, only two live this close to the pole.

The big ones are Emperors.

The small one is an Adelie.

The penguins only look awkward on the surface.

They are completely at home.

Five hours after takeoff, the plane lands on the frozen sea near McMurdo Station, a United States research base.

For the passengers, those five hours have transformed their world.

- [Man] Thanks for flying with us.

- [Christian] It's like getting out on another planet.

I'm always impressed with the purity and the vastness of the ice.

The sea we want to explore is beneath our feet, locked away under six feet of ice.

But first we have to learn to deal with the ice.

- This is Snow Craft One.

This is the basic snow survival course that all field parties have to attend in order to get permitted to head out into the field.

In the height of the winter, the sea ice is growing, the continent roughly doubles in size.

So in a normal year, you'll pretty much see a lot of little cracks and the sea ice out here.

What we're gonna do here is we're just gonna break out our drills and just find out how thick the ice is here.

Whenever you're gonna drill, and drilling, is considering the potential hazards out here, that's the way to find out whether the ice you're on is safe or not.

It's known as Snow Craft One, also collectively known as Happy Camper School and sometimes known as Survival School.

I guess a lot that depends on the weather and the disposition of the folks involved.

But today, it is definitely Happy Camper School.

- Well, this is a couch.

See?

This is the party couch.

And I think I'll turn this into like a little drink rest or coffee table.

- Okay, high winds coming in from the South.

[man imitating wind blowing] You're gonna have to hold onto everything you've got.

You can't just take the contents of your tents and dump it onto the ground, because otherwise it's just gonna blow away.

And for God's sakes, you don't take the thing and try and blow into it.

You're gonna wind up in medical.

[man murmuring] - This is a classic Antarctic day out here, it's virtually dead calm, lots of sunshine, but the potential for it to change in the next two hours or less is pretty dramatic and pretty amazing.

Intimidating, I think is the probably the best word for it.

The weather is just plain intimidating.

The way it can humiliate you and make you feel small.

[wind howling] - [Narrator] It's mid-October, springtime at McMurdo Station.

- If you have any trouble at all, you just call Mac Ops and tell 'em you have a dive accident.

They'll page everyone.

- [Narrator] Hundreds of scientists and technicians are here, but most of them, like Norb's team, are inside getting ready for the season's work.

- Transportation options will be best.

If you're diving locally here, the best transportation is going to be your Spryte.

- [Narrator] Rob Robbins is McMurdo's diving coordinator.

He'll often dive with the team.

- They have a helicopter launch from here, go up there and pick you up, so... - [Narrator] People call this place MacTown.

It's a frontier outpost, a modern version of an old mining town.

When the weather breaks, everyone scrambles to get out in the field.

They're all chasing the most elusive kind of gold: knowledge.

This year, the National Science Foundation will support 127 major research projects.

The projects cover everything from microscopic worms in the ground, to the movement of ice sheets, to the hole in the ozone, to the crystals made in the big volcano called Erebus, the dominant landmark here.

- [Man On Radio] 3500 back in to MacTown.

- [Narrator] For Norb, Christian, and Dale, gathering equipment and scheduling trips into the field seems to occupy all the daylight hours, and it's daylight all the time.

- So what we may wanna do is fly up here, see if you like anything, we can land anywhere around there, down there, take the door off, and do it again.

And just pull it off.

We'll put a rock on the door and leave it.

- [Narrator] All this work is dwarfed by Antarctica.

It's the only place on Earth that still has huge areas which have never seen the track of a human being.

- [Christian] I'm so ready to dive, I'll dig with a toothpick if I have to.

But we still have to plan things out with Rob.

- There's a lot of accessible dive sites around here.

There's a lot of good diving.

At Cape Armitage, it's fairly shallow.

There's a shoal there, there's a lot of anchor ice, it's really pretty spectacular.

Little Razorback, which is maybe an hour away or so, a lot of big pressure ridges there, so that's a good spot.

- Are we gonna be able to cross them?

You think the travel's gonna be bad?

- The travel I think is gonna be pretty good.

There are some cracks.

You're gonna wanna be careful, but it's fairly safe out there.

- I'd really like to film an iceberg underwater.

I mean, that's kind of this thing, you know.

- There's an iceberg grounded up at Cape Barne which could be spectacular, but it looks like it's quite a ways offshore.

Have to see what it pans out to be.

- [Christian] This ice is six feet thick.

It's like cutting a porthole in a concrete wall.

But we can't just go jump in the hole.

- Come back in and blade it, and we'll bring the hut in and place the hut and we'll put snow around it.

[people chattering] [seals chattering] - [Narrator] Weddell seals are at home on the ice.

They live far from open water and use cracks and holes to get in and out of the water and to breathe.

In October and November, the seals haul themselves out on the ice to give birth and raise pups.

- [Norb] After 10 days of preparation, we're ready.

I admit it.

I'm a wimpy diver.

I hate boats, I get seasick.

This is great.

No waves.

You just drive out on a frozen ocean in this big red thing, which is called a Spryte.

[engine rumbling] - [Christian] A Spryte is fun for about the first five minutes.

It's like driving a tank.

But a tank's fast.

This thing maxes out at about 10 miles an hour.

After five minutes, it's sheer unadulterated hell.

- [Narrator] After a rough hour's ride over the frozen ocean, the team arrives at the dive hut that they place next to a rock called Little Razorback Island.

[adventurous music] Dale will be first into the water.

- [Dale] Three layers of underwear and a dry suit.

It still doesn't really keep you warm, but for me, it's worth it.

There's no diving like this anywhere else in the world.

The only thing exposed to the water is your lips.

At first they burn, but then they get completely numb and it's okay.

[water splashing] - [Narrator] The water temperature here is 28 degrees, so cold it can freeze blood.

If something goes wrong, there are only two places to get out, this hole and a nearby safety hole.

But diving is what they came all this way to do.

[mysterious music] - [Dale] The crystals on the bottom are called anchor ice.

In shallow places like this, ice forms on almost anything the water touches, so it grows in kind of an ice garden.

Sometimes it picks up stones or even living creatures like this sea urchin and then carries them up to the ceiling.

[seals squeaking and chirping] - [Christian] To me, these noises sound like alien radio signals in science fiction movies.

They're actually the calls of Wheddell seals.

The seals will go anywhere they can find a hole for air.

[mysterious music] - [Norb] I've died in a lot of places that are famous for clear water.

The Great Barrier Reef, the Bahamas, Tahiti, Hawaii.

This is far clearer.

At this time of year, you can see almost a quarter of a mile.

- [Dale] These strange things are called brine channels.

Up on the surface, salt is concentrated in the frozen sea ice and makes brine, which is so salty that it stays liquid even when the surface ice cools it to extremely low temperatures.

When this cold brine flows downward, it freezes the less salty sea water around it, making these tubes.

We're diving in shallow water because most of the action is on the ocean floor.

These sea stars have just finished off an urchin and are attacking each other.

Some of these animals are far bigger than similar species elsewhere.

This sea spider is a giant compared to its cousins that live in warmer water.

Isolation helps these animals evolve differently, and their slow metabolism in the cold lets them grow older and bigger.

- [Norb] Clear water is great for us, but hard on the life here.

There's been no sunlight for four months, so nothing has been growing in the water.

Everything is hungry.

[ominous music] This anemone may look pretty, but it's a ravenous predator.

The current has carried this jelly too close to the bottom.

The anemone snagged it.

Sometimes they can eat an entire jelly.

- [Dale] After about 40 minutes you start to really get cold.

It's time to get back to that warm hut.

Under the ice, you have no clue what the weather's been doing.

But this is Antarctica.

It's sure to be different.

When you come out, you get oriented by looking for Mount Erebus.

There it is, smoking away in the distance.

- [Narrator] Underwater, the body fights off cold by burning calories like a furnace.

Everyone is physically exhausted.

- [Man] Very, very cool.

- [Dale] But the whole blue room sensation of dropping down out of the second tunnel and then looking up [gasps] into the blue room, that's pretty, that's a sensation.

Right there.

- [Narrator] But other than being tired, they're exhilarated.

- I think it must be because you're coming out of that dark part, right?

- Exactly.

- Because otherwise, you're just... - Kinda spooky.

- Scary.

- It's kinda fun.

- [Narrator] The next day, they're right back out on the ice.

The team comes upon a hump in the snow that could be a lot more dangerous than it looks.

This is exactly what Norb and Dale were warned about in survival school.

- So what's the rule thumb?

It has to be... We need 30 inches ice, but could be a crack.

- It's gotta be less than a third sort of the track width.

So, I think if we just get a shovel here and we can clear some of this away and see how wide it is.

- [Narrator] This snow drift marks a crack in the ice.

You can't tell from the surface if the crack is too wide for the Spryte to cross.

- [Dale] It's always weird to think that right underneath this solid looking surface, there's ocean a thousand feet deep.

I love diving, but I sure don't want to fall in.

- [Narrator] The penguins know how to get around better than the team.

In fact, research has shown that their funny waddle is actually very efficient.

There are all sorts of mysteries under the ice.

One of them is how the Wooddell seals live.

In this field camp near McMurdo, biologists are studying the seals.

They have drilled a hole in the ice so far from the other holes that a seal released here has to come back.

It's held captive by its need to breathe.

under a special research permit, this male was captured and he'll work with the scientists for a couple of weeks, then be returned to the place he was caught.

They have glued instruments on his back and a camera on his head to explore a world of life and hunting under the ice that would otherwise be hidden forever.

An observation chamber has been built under the ice near the hole.

One of the science team is there to watch the seal's behavior.

This seal, and others that have worn the equipment, have led to breakthroughs in the study of Weddells.

The video the seal takes is a first.

Here, with the camera pointed forward, is something divers and scientists had never seen before.

The seal blows bubbles at the sea ice ceiling and flushes out its prey.

The ice is too thin for vehicles near Turtle Rock, which is the best place to see seals underwater.

The team must hike with tanks, cameras, weight belts, and all.

Underwater, a male seal hears them approach.

He checks them out.

But he has other things on his mind.

There is a female in the neighborhood.

There's no warm dive hut here, but that's all right.

It's a balmy day.

About 15 degrees.

Since the big drill can't get here, the team has to dive through a seal hole.

The water's constantly refreezing, but keeping the hole open is one thing the divers can do more easily than the seals.

Seals have to use their teeth.

- Do you hear it going or not?

- [Man] What?

- Do you hear it going when I press it?

- Not making a lot of noise, though.

- [indistinct] anyway.

The details get you every time.

I've had trouble with this hose before, so I want to be real sure it's working.

[metal clanking] - There we go.

- Yep.

You can throw on that one.

- It's frozen.

- All right.

- [Narrator] As Norb and Christian get in the water, a mother seal is teaching her baby to swim.

But she has other concerns, too.

Females, once they've given birth, are often ready to breed, and this female knows that the male is around.

[seal chirping] - [Christian] Seals can dive as deep as 2000 feet.

They have been known to stany underwater for over an hour.

But they don't get decompression sickness, the bends, which is a major hazard for divers.

To prevent the bends, divers must be careful when ascending, so nitrogen doesn't fizz out of their blood, like bubbles in a soft drink.

[seal chirping] - [Norb] As we watch, a male shows up to chase the female.

[seal chirping] But she's not interested.

The males sometimes fight each other at breathing holes, so we try to use holes that aren't occupied.

As Christian heads for the hole to get out, something unexpected happens.

- Got it.

- Oh.

- Oh my god.

- Please don't bite me, please don't bite me.

Please don't bite me.

- Oh my.

- Oh, you're gonna get bit.

- [Norb] He thinks it's a huge male about to take a chunk out of a part of him that Christian doesn't want to lose.

- [Christian] Like, whoa, somebody's goosing me!

[people laughing] - Saw that baby seal go... [man laughing] - Like, don't bite me, don't bite me!

- That mom didn't care at all, man.

- Was that the baby that came up, then?

- Yeah.

- I was like, holy...

I saw a big, big dude over here scraping out a hole.

- [Narrator] This big one is a leopard seal.

He's near the top of the food chain.

A wolf of the Antarctic.

A penguin eater.

But out on the surface, he's about as agile as a slug, so the penguin is safe, for now.

Couloir Cliffs, the next dive site, is too far away from McMurdo Station for the team to use a drilling rig.

But Christian, Rob, and Dale use just about every portable tool known to man... [tools buzzing] To get through the ice.

- Sorry.

- We have hole.

[eerie music] - [Norb] This is a type of sea star that I have never seen before, using its long arms to pick plankton out of the water as the current moves past.

This crinoid, our relative of sea stars, is sort of fly casting for plankton.

- [Narrator] On the surface, Rob keeps the hole clear, and has no idea that beneath him, Dale is having one of the most memorable dives of his life.

He is witnessing the effects created when snow from these cliffs melts and sinks beneath the cracks in the rocks.

- [Dale] Under the surface, the fresh water seeping back out from the rocks is frozen by the colder sea water.

It looks like a frozen waterfall.

The sunshine has been feeding energy to algae, which is turning green and golden.

Soon the algae will bloom in the water and end our season by ruining the visibility.

But for now, it's just plain beautiful.

- [Narrator] On a slope below Mount Erebus, a glacier flows to the sea from the thick ice in the interior.

In some ages of the Earth's history, Antarctica's ice has flowed completely away.

Today scientists are studying this ice, trying to learn whether it is growing or shrinking, and why.

This simple and precarious balance between what is frozen and what is not affects everyone on Earth.

[helicopter whirring] Norb's team has put a hut right where the glacier meets both rock and the sea.

The glacier face goes hundreds of feet down into the water.

Norb and Christian will dive right next to it.

[mysterious music] - [Christian] This is a spooky place.

When you swim close to this, you can't really tell where the water ends and the ice begins.

It gives you kind of a ominous feeling.

You see all this big ice, but fish live right next to it, no problem.

They make their own antifreeze in their pale blood.

The ice isn't ominous to them, it's home.

- [Narrator] Every year, Antarctica sheds thousands of icebergs like flakes of its skin.

Everyone knows that icebergs hide most of their mass underwater, which is why the team wants to shoot near one.

But that, like everything else here, is going to be harder than they thought.

Christian and Rob have been out for two days looking for bergs to explore.

Their report is not good.

- Dave.

- Hey.

- How'd it go at Cape Roberts?

- Well, Cape Roberts is pretty nice, but we weren't able to find any diveable icebergs.

- Oh, you're kidding.

- No, actually, we tried quite a bit.

We spent a couple days chainsawing holes and trying things out, but doesn't look too good.

- Oh, really?

So you're saying out of all those bergs over there, you don't think any one of em's diveable?

- I don't think any of 'em are diveable without drilling or blasting a hole.

Most of the icebergs are packed tight by the sea ice.

No cracks, no openings, no nothing, and a lot of snow drifted up around each of 'em.

We did find one berg that had kind of calved off and collapsed, and as it collapsed, it broke the surrounding sea ice around it, which looked really good.

It looked like there was some thin spots we can get in and there was a seal or two around.

We spent like five hours chainsawing this thing open enough so that we could get in.

Turns out, not only was it really dark and murky and kinda freaky, but...

It looked as if when the iceberg calved and it broke all the sea ice around it, it pushed all that broken sea ice underneath the surrounding sea ice.

So as soon as you open up a hole, it could be plugged up by this broken piece of ice that's underneath the... - No, it's dangerous.

- So I kind of jumped in and went down about eight or 10 feet, and all the ice started kind of shifting around me, and so I came back up.

Didn't like it.

- [Narrator] But the team is determined to dive an iceberg, and find this berg frozen in the sea ice.

The berg appears to be in very deep water.

Not the most interesting diving.

But at least there's a seal hole to dive through, and what they discover is a complete surprise.

[mysterious music] - [Christian] This is very cool.

There's rock right under the berg.

It's not in deep water after all.

There's an underwater pinnacle here, and the berg crashed into it like a ship hitting a reef.

But a ship would be here for centuries.

It's hard to imagine, but soon this huge structure will just disappear.

- [Dale] Bergs play a huge role in the Antarctic ecosystem.

They crash into the bottom often, clearing big swaths on the sea floor for new life to colonize.

Some scientists think this constant churning of the bottom is one of the reasons that life down here is so diverse.

I've seen these dimples on most bergs.

They may be caused by the way the ice is eroded by currents swirling against it.

Young fish take refuge in the dimples.

I guess when this berg melts, they'll just go find another one.

It's not as if there's a shortage.

This is a Desmodina, the same kind of jelly that was nailed by the anemone.

It's riding higher in the current, though, fishing with 40-foot long tentacles.

- [Narrator] It has been another great dive, but this dive costs the team, big time.

- I'm calling from McMurdo Station in Antarctica.

I'm a physician, I'm a diver, and I have somebody here who's a professional diver who truly seems like he has decompression sickness.

Diving down here- - [Narrator] Dale is in trouble.

He may have the bends.

- [Doctor] Diving heavily for a week.

- [Dale] It's a sharp pain in my back and I don't want to mess with it.

If there's a bubble in there, you never know.

You can be paralyzed for the rest of your life.

- He awoke.

- [Dale] Sometimes you just don't recover, and you can't dive ever again.

- Kind of a tough one.

Now, we do have a chamber here, and the chamber is standing by.

- All right, get in.

- Here we go.

- See ya.

- Bye.

- [Dale] Imagine being told that you can no longer do something that has been a large part of your life since you were a child.

- [Woman] 30 seconds for descent to 30 feet.

- [Narrator] Dale has been placed in a hyperbaric chamber, an enclosure in which air pressure is first gradually increased and then gradually decreased.

This shrinks the nitrogen bubbles in Dale's tissues and allows the extra nitrogen gas to safely diffuse out of his body.

- [Dale] I feel selfish for being depressed about losing what some may consider to be a hazardous job.

Most of all, I'll miss being underwater, under the ice.

- [Narrator] Dale will help out on the surface as the team continues diving and filming.

They fly to the strangest dive site on the schedule.

It's near a region called the Dry Valleys, where wind keeps the rock scoured clear of ice.

At the foot of these valleys is sea ice that is unusually thick and stable.

Near the ice, the National Science Foundation has built a well-equipped field camp.

Here, oceanographers are studying life that is remarkably similar to what lives thousands of feet down on the ocean floor, the largest and least-known ecosystem on Earth.

But the depth here is only 90 feet.

It's the ice, so thick it never breaks up, that makes this shallow world as dark and cold as the bed of the deep sea.

- [Norb] These unusual soft corals have evolved to sweep the sand for food, a behavior that has never been seen anywhere else.

[tense music] Among scallops, these brutal stars fight each other like stick warriors.

The red ones eat the white ones, if they can catch them.

- [Narrator] It's January.

On the shore, water is cut loose by temperatures that flirt with a thaw.

But summer ages quickly.

The midnight sun sinks toward the first sunset of autumn, and there are new visitors to McMurdo Sound.

[ice rumbling] The US Coast Guard icebreaker Polar Star arrives to cut a passage for a freighter to bring in supplies to MacTown.

In the strips of open water behind the icebreaker, minke whales appear.

They're feeding on plankton that has bloomed in the water under the ice in the constant daylight.

Minkes, among the most common whales in the world, are still hunted in Antarctic waters.

The sudden appearance of abundant food is good for them, but bad for diving.

The great visibility is gone, so Norb's time here is almost over.

All around the coast of Antarctica, ice cracks and disintegrates.

The expanse of sea ice has shrunk from its maximum of seven million square miles to its minimum of only about one million.

There are other visitors out there, but they're more elusive.

For days, the team searches outside McMurdo, looking for the orcas that often haunt the ice edge.

But day after day, the patches of water are empty.

Then in one breath everything changes.

- [Norb] The ice of the whole bay seems to be breaking up in front of our eyes, opening into long strips of water that are called leads.

The orcas take advantage of these leads as soon as they open to get as far into the ice as they can.

They are hunting the giant Antarctic cod, a fish that can reach over 100 pounds and uses the ice edge as shelter.

- [Narrator] Everyone thinks that orcas eat penguins.

These Adelie penguins seem to think so too.

But scientists haven't actually seen a penguin eaten here, so they don't know for sure that it happens.

Still, when whales are around, penguins play it safe.

- Woohoo!

- Yeah!

[people shouting indistinctly] - [Man] Dude, this is ridiculous.

[laughing] - [Man] There's like three whales right there.

- [Norb] Orcas seem to watch us by doing what we call spy hopping, checking out the surface.

They may also spy hop to look for new leads or to navigate back to open water.

- [Narrator] The orcas seem to be at the heart of the huge ebb and flow of energy in the Antarctic sea, where the sun burns away the ice each year and the long night builds it back.

- [Norb] On our last day, Rob is filming me with his digital camera, and suddenly something happens that reminds me that for all our study, we still know very little about life under the ice.

The whale checks me out, then sends some kind of message, but I have no idea what it means.

[mysterious music] - [Narrator] Months ago, Norb, Christian, and Dale said they were "going to the ice."

There is no casual term for leaving it.

[helicopter whirring] They have looked in the face of glaciers and at the roots of icebergs.

They have glimpsed the life that has turned this hostile place into a home.

But it's tough being on the ice, and at the end of all this work and cold, the team is happy to be heading home.

Antarctica is the one continent where humans may forever be strangers.

But we have looked past the big white shield and have seen the beauty and mystery that the ice tries to hide.

- [Announcer] This program was made possible by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

[adventurous music] [gentle music]