>> San Francisco?

>> Yes.

>> Oh, man, I'm gonna tell you

about San Francisco.

San Francisco ain't for me.

I mean, ever since I got out of

high school, I had a couple of

jobs.

I worked at a couple of past

companies and, uh, warehouses.

I mean, after a while, they say,

"Well, I guess we gonna lay you

off for a couple of weeks,"

you know.

They talk about the South.

The South is not half as bad

as San Francisco.

You want to tell me about

San Francisco?

I'll tell you about

San Francisco.

The white man, he's not --

He's not takin' advantage of you

out in public like they doin'

down in Birmingham.

But he's killin' you with that

pencil and paper, brother.

When you go to look for a job,

can you get a job?

Can you get a job, Winkle?

>> This is the San Francisco

Americans pretend does not

exist.

They think I'm making it up.

>> National Educational

Television presents...

"Take This Hammer."

>> ♪ Take this hammer ♪

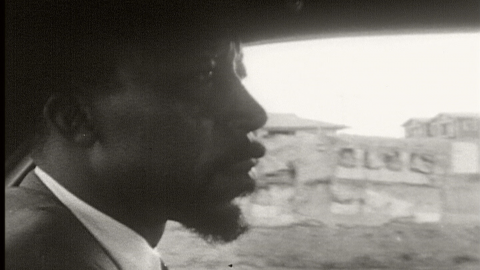

>> This is a film report on a

visit to the city of

San Francisco by the novelist,

essayist, and playwright

James Baldwin.

Mr. Baldwin's guide on this tour

of the city is the

executive director

of Youth For Service,

Orville Luster.

>> ♪ Take this hammer ♪

♪ And carry it to the captain ♪

♪ You tell him I'm gone ♪

♪ You tell him I'm gone ♪

>> The drive from the airport

into any American city looks

pretty much the same.

You could be anywhere.

But for James Baldwin,

this similarity goes deeper.

On the drive into San Francisco,

Baldwin began talking about

the increasing bitterness,

demoralization, and despair of

Negro youths in northern cities.

And it was decided that we would

explore the existence of such

attitudes and conditions in the

city of San Francisco, with its

widely advertised liberal

and cosmopolitan traditions.

Baldwin also talked about his

concept of dues paying,

or living up to one's

responsibility, and commented

that many northerners seem to

feel that because they do not

live in Mississippi, they are

somehow paying their dues.

>> I think the truth is that

everyone, on the one hand, is

fundamentally capable of paying

his dues, but no one pays his

dues willingly.

You know?

And the white man, like the

black man, like any other man on

Earth, can pay his dues if he

realizes that that's what he's

got to do.

As long as you think there's

some way to get through life

without paying your dues,

you're gonna be bankrupt.

The bill has come in.

It's not coming in. It is in.

And the very question now

is precisely what we've got

in the bank.

This will cost us everything

we think we have.

Everything.

And Birmingham is an incident,

you know, which may become a

shrine.

What is really crucial is

whether or not the country,

the people in the country, the

citizenry, are able to recognize

that there is no moral distance,

no moral distance,

which is to say no distance

between the facts of life

in San Francisco and the facts

of life in Birmingham.

We've got to call, you know,

we've got to tell it like it is.

And that's where it's at.

>> ♪ Oh, I said I wasn't gonna

tell nobody ♪

♪ But I ♪

>> ♪ Couldn't keep it to

myself ♪

>> ♪ Oh, I ♪

>> ♪ Couldn't keep it to

myself ♪

>> ♪ Oh, I ♪

>> ♪ Couldn't keep it to

myself ♪

>> ♪ Said I wasn't gonna tell

nobody ♪

♪ But I ♪

>> ♪ Couldn't keep it to

myself ♪

>> ♪ Oh, I ♪

>> ♪ What the lord has done for

me ♪

>> ♪ Oh, I said I wasn't gonna

tell nobody ♪

♪ But I ♪

>> ♪ Couldn't keep it to

myself ♪

>> ♪ Oh, I ♪

>> ♪ Couldn't keep it to

myself ♪

>> ♪ Oh, I ♪

>> ♪ Couldn't keep it to

myself ♪

>> ♪ I said I wasn't gonna tell

nobody ♪

♪ But I ♪

>> I imagine it'd be easy for

any white person walking through

San Francisco to imagine that

everything was at peace because

it certainly looks it that way,

you know, on the surface.

San Francisco's much prettier

than New York.

And it's easier to hide in

San Francisco than it is in

New York because you've got the

view, you've got the hills.

You've got the San Francisco

legend, too, which is that

it's cosmopolitan and

forward-looking.

But it's just another American

city.

And if you're a black man, that

means that's a very bitter thing

to say.

Children are dying here as they

are in New York for the very

same reason.

But, see, it's a somewhat better

place to lie about it.

That's really all it comes to.

Nobody wants to destroy the

image of San Francisco.

>> Old city.

>> Oh, yes. Yes.

>> I'd like to acquaint you

with, uh, San Francisco

as a whole, Mr. Baldwin.

And I think, mostly, that what's

being watched here today is

somethin' black, and the young

people go to school together,

they graduate off the same

stage, and then when it comes to

jobs, the black face is not

qualified, but they graduate.

Then my daughter has to go clean

up the same girl's house that

she graduates off the stage.

As I said, the most that's

being watched is the black face.

>> What we were talking about

last night, coming in from the

airport, was the real situation

of Negroes in this city...

>> Yes.

>> ...as opposed to the image...

>> That's right.

>> ...San Francisco would like

to present.

>> Yes.

>> Well, why don't you tell me

a little bit about it?

I know a lot about New York,

but I'm a stranger here.

Let's say I'm sure the --

I'm sure the, um, principle

holds, but I'm curious about the

details.

>> Well, one thing about it

in this particular area,

about 80% of the people in this

area are Negro.

This is a real large housing

project.

There's -- As far as delinquency

is concerned, we rank about

fourth.

The job situation is bad.

This is a real black belt

of San Francisco.

I think that, uh,

the lady over to your left,

Mrs. Nichols, is a good

representative of one of the

indigenous leaders in this area.

>> Tell me something.

It may sound like a stupid

question, but it's a question I

have to ask myself all the time.

What, precisely, do you say

to a Negro kid, um...

to, um...invest him with...

a morale which the country

is determined he shan't have?

Or to spell that out much more

specifically, when dealing with

a Negro kid and trying to insist

that he know that he can do

anything he wants to do,

how do you make him believe it?

>> That's a difficult question.

I think that, uh,

that one of the main things

that we have to make and

believe...

You know,

they say everybody can be the

President of the United States.

>> That's true.

>> And then, uh...this boy,

uh, grows up and he comes up.

But by the time he gets 14 or

15 years old, he begins to find

out that, uh, that, uh, this --

this is not true and to make

him, uh, face --

be able to face what's coming to

him in the future.

>> ....be a Negro president

in this country.

>> There'll never be a Negro

president in this country?

Why do you say that?

>> We can't get jobs.

How we gonna be a president?

>> Exactly.

But I want you to think about

this.

There will be a Negro president

of this country, but it will not

be the country that we are

sitting in now.

What if you say to yourself,

"There never will be a Negro

president of this country?"

And what you're doing

is agreeing with white people

who say you are inferior.

It's not important, really, you

know, whether or not there's a

Negro president, I mean, in that

way.

What's important is that you

should realize that you can

become -- you can become the

President.

There's nothing anybody --

anybody can do that you can't

do.

>> Well, the truth is if you get

them, if you get --

I don't -- I don't think this is

an exaggeration.

I think the truth still is that

even when you get to the most

meager opportunity, you've got

to be at least five times as

good as anybody else around,

five times as good not only at

the job, but...

This is what is so dangerous,

I think.

You have to have a certain...

The boys that I grew up with,

I grew up in the streets

in Harlem.

And of the survivors,

what marks all the survivors

is a certain ruthlessness

which was absolutely

indispensable when -- when we're

going to survive.

>> I can do it.

I can do it. I can do it.

I don't have to work --

I don't have to work for nobody

and I can make it.

I don't have to work --

>> But how do you make it?

>> What you mean, how I make it?

This is something -- I'm not

gonna tell you how I make it.

Lookit, I'm indicting myself,

brother, talking to you.

You go back and tell the police

what I did.

[ Laughter ]

>> I didn't say you were doin'

nothin'.

>> No, you're doing that for --

What if I tell you that I robbed

a bank in Los Angeles?

You believe that?

>> Well, no, if you --

if you don't say you did.

>> I ain't gonna say I did,

neither.

>> The things you'll be talking

about now, their real problem

is that they cannot find,

in the country, any -- any

reason to accept anything the

country says.

And they're very young, so they

can't find anything else,

either.

And this is how they end up,

for example, on the needle.

It's a crime committed by

one section of the population,

of the populace,

against another section

of the populace.

And it's a crime which really

could destroy this country.

>> What do you think about the

police?

>> I think they have a purpose.

But, then again, the way some of

these people do you sometimes

when they pick you up and stop

you...

Or, like, a couple of times

we'd be downtown just walkin'

around, they'd look at you.

If you look suspicious,

they would just stop you.

Like, I was goin' to a show

one night, me and my wife.

And we just happened to go

around Market Street, and we

seen this police car go by.

All right, we can turn the

corner then make the corner.

They meet us. And they stop us.

Our show starts at 7:45.

We were out there till 9:00.

But then they didn't have no

excuse to stop us.

But they stopped us, searched

the car, call in, and this and

that.

And what was the purpose of

that?

We weren't doing anything wrong.

Nobody was mad.

Let me ask you one thing.

What do police do when they get

mad?

>> What do the police do when

they get mad?

>> I mean, we ordinary citizens.

When we get mad, we can do

things to hurt people and rob

and steal.

What -- what do they do when

they get mad?

Who do they take their steam off

on?

>> I think you know the answer

to that question.

>> Well, I couldn't answer that

because the police has never

bothered me in that way.

But I read newspapers, and I've

been livin' around here all my

life and I see things goin' on.

>> Mm-hmm.

Well, when a policeman gets mad,

he's got a gun.

And he's got a club.

Yeah.

>> It's one thing

that's different in, uh,

San Francisco and Birmingham,

it is that San Francisco is

whitewash.

>> Yeah. Precisely.

>> Yeah.

>> In San Francisco, it's under

the rug.

>> Yeah.

>> You know, it hasn't hit the

headlines yet, and everyone --

everyone in San Francisco,

every white person in

San Francisco pretend they

haven't got a Negro problem.

Everywhere I have been in this

country, if you talk to a white

person, he says race relations

are excellent, and I've yet to

find a single Negro in this

country who agrees with that.

>> And then if you ask that the

Negro have a better opportunity,

ask that Negro be hired in a

large firm, they only reach out

and hire one just to shut your

mouth.

>> And put him in the window.

>> Well, Mr. Baldwin, I'd like

to also say that Hunters Point

seems to me, in my opinion,

the way you're lookin' at it,

Hunters Point is just like

being in Alabama right now.

>> Mm-hmm.

>> And I feel that we don't --

some of the ones that can't go

down, we can -- we can march on

San Francisco for the black man,

to help the black woman.

We can do that here because it

has been stated that until we

work on this, San Francisco

and other areas --New York and

all Chicago and all around --

that we can get something done.

We can help our brothers

in the South.

>> In the South, yes.

>> Those -- The black people

in Alabama are my people.

>> Yes, yeah.

>> Primarily, I'm from Texas.

>> Mm-hmm.

>> But anywhere in the South,

anywhere a Negro is -- a black

man is involved, I'm there.

>> Mm-hmm.

>> I'm the mother of five kids,

the mother of a 9-week-old baby.

But if the time comes where

I can't march here in

San Francisco, I certainly will

beg, borrow a ticket to go to

Alabama.

>> Mm-hmm.

>> And I am ready.

>> ♪ You are the reason ♪

>> ♪ You're the reason ♪

>> ♪ That saved my soul ♪

>> ♪ Saved my soul ♪

>> ♪ That Sunday morning ♪

>> ♪ Sunday morning ♪

>> ♪ I put my ♪

>> ♪ Knees on the ground ♪

>> ♪ Oh ♪

>> I suppose that no one in

San Francisco has any sense of

what a dangerous area this is.

And I think this is one of the

real troubles that the Negro has

in San Francisco --

He doesn't really know his place

because it hasn't been really

spelled out.

>> Yeah.

>> And he's trying to find his

place, and it's so...

This is one of the problems,

you know what I mean?

What place is there for me?

You know, he came out to escape.

And then you keep trying...

>> And this is another prison.

>> That's right. You know?

And you find yourself facin' the

Pacific Ocean, you know?

>> Yeah.

>> There's no place else to go.

>> Yes. Yeah.

>> You know?

Now, you can see this is...

>> Yeah.

>> More residences and even

apartments and so forth.

Coming down, we will soon be

to Market Street.

>> The great problem is how in

the world one is going to

invest these children with a new

morale, a sense of their own

worth because the country isn't

gonna do it.

The country won't do it.

I suppose one can say as long as

the country can't do it, then

he'll be able to choose his own

worth.

>> We have no race here.

We have no race at all.

>> We have no flags.

>> No.

>> No cut.

>> Think they're better.

>> No.

>> The white man? Oh!

>> Tell me what you mean.

>> You know what I mean?

>> Take what you want.

>> Huh? Tell me what you mean.

>> What I mean?

>> Yeah.

>> I mean, I'm tryin'...

>> No, we gonna tell it, man.

We gonna tell it.

>> I don't have nothin' over

here.

>> No, no.

>> Nothing over here?

>> Nothing.

I don't have anything.

>> Where the man at?

>> How long you felt that way?

>> How long I felt that way?

Since 1956.

>> Since 1956?

>> Yeah.

>> Why did you feel that way?

>> Huh?

>> Why did you feel that way?

>> Because I realized what a dog

the white man was.

>> How did you come to realize

it?

>> When he got to start jumpin'

on me and puttin' me in jail and

everything, you know.

>> Where did that happen?

>> Where?

Right here in San Francisco...

>> Right here in San Francisco?

>> California. Wasn't nothin'.

>> Tell me how it started.

>> How it started?

What you mean, how it started?

>> Tell me about the first time

you were arrested.

>> First time I was arrested?

>> Yeah.

>> Well, that was...

>> That was in 1948.

>> That was in 1948?

>> Yeah.

>> What for?

>> Well, I don't know what they

call it, but I got caught in a

bedroom with a little white

girl, said she was a juvenile.

>> [ Laughs ] Where was that?

>> Right here in San Francisco.

>> In San Francisco?

>> Yeah.

>> How old were you in 1948?

>> 8.

>> What?

>> 8.

>> Never let the white man catch

you on your knees, brother.

>> You were 8 years old in 19...

>> Yeah.

>> You were 8 years old in 1948?

>> Yeah.

>> And you were caught in bed

with a little white girl?

>> Yeah.

>> And you went to jail?

>> Yeah.

>> When you were 8?

>> Yeah.

>> In San Francisco?

>> Yeah.

>> And, lookit, you learn from

the world you live in, brother.

This white man ain't teach you

nothin' in his book but what you

ought to know, and you ain't

gonna know nothin' about it...

>> He's not even teachin' me

about the future of my people.

>> What you goin' to school

for then, dummy?

>> We don't even have a country.

>> I know that.

>> Do we have a country?

>> He's sayin' you ought to

think this is your country,

which is not your country.

What flag is a black man's flag?

We have no flag, brother.

No flag at all.

>> People, people,

we not gonna get nothin',

not by sittin' around here

doin' this sit-in demonstrations

or nothin'.

People not gonna do anything for

us.

>> Well, how are we gonna do it?

>> Huh? By violence. Violence.

>> And when you say...

>> By uprisin', having a

revolution.

>> But there are 20 million of

us.

>> 20 million? That's enough.

>> Not these days and not in

those terms.

>> Oh, it's enough.

>> They're scattered. 48 states.

>> 48 states? Get 'em together.

>> How?

>> How? Through Islam.

>> What?

>> The true religion, you know.

Get all the people together, get

'em all believin' one thing, and

then they can't help but stick

together.

I mean, we can't stick together

now, half of us Christians,

the other half Baptists, you

know, some Jews and all that.

And what good is that gonna do

us?

>> Catholics. Mm-hmm.

>> So you think the only thing

we can do...

>> Is get together.

>> ...is have an armed uprising?

>> Really.

Just with blood, you know?

Let everybody bleed a little

bit.

That's the only way we're gonna

get anything.

What happened to the people in

Birmingham?

>> Well, Birmingham isn't over

yet.

>> Oh, it's over.

Oh, yeah. It's over.

>> It's over.

>> It's over.

>> They done sent in the state

troopers, the federal.

It's all over now.

People, they had a little old,

you know, little old show

Sunday night and all.

That was the only thing they

did.

When they was marchin' around

in them thousands and thousands,

wasn't nothin' happenin'.

They got mad Sunday.

Jumped on a few of 'em, sent a

few of 'em to the hospital.

And then what happens?

They say, "We gonna give you

what you want," huh?

Yeah. That ain't nothin'.

Ain't gonna get nothin'.

>> Now, the Negro teenager...

He doesn't have any possibility

as we sit here now -- I mean, as

of this moment, this is not

historical -- does not have any

possibility of accepting

American history, which is to

say, he has no way of learning

it because it has not been

and it is not being taught.

Yet, there is no possibility

for him to begin to act on what

we always like to think of as

the American assumptions, you

know, a man's a man for all that

and all that jazz.

It isn't that he wouldn't.

It's because there's no

possibility of his doing so

because the country intends to

keep him in his place and still

does because the only way a

Negro teenager can make it is to

step outside that system, you

know, to become an effective

criminal on whatever level, you

know, to become an operator, you

know, like they need to make it,

or to turn to Malcolm X.

>> They tryin' to tear down our

homes, brother, and when the

white man try to tear down your

home, then it's time for you to

do somethin'.

But what can we do?

We don't know anything about

what's goin' on.

I mean, we try to go to the

meeting and things like that.

We watch the television.

We watch all this

about Birmingham down there.

Just like Malcolm X said

yesterday on television,

he said, "The white man, he talk

about truth."

And, uh, this man, Mr. King,

he down there talkin' about,

"Yeah, can we get some kinda --

Can we get some kinda

cooperation?

Can we get some kinda truth

down there?"

Oh, what are they doin'

down there?

They not doin' anything.

See, I'm callin' him a chump,

just like Malcolm X call it.

He's a chump, and I think a

black Muslim is right in some of

his doings.

And I think that a truce down

there is impossible.

It's utterly impossible.

It's fantastic and it's

unbelievable.

[ Applause ]

Wait, wait, wait, wait, wait.

Wait, wait, let me tell you.

Now, they talkin' about better

jobs -- jobs right here.

You want me to tell you what

kind of job they gonna give us?

They gonna let us tear down our

own homes out here on

Hunters Point.

That's the job we gettin'.

And you know what they gonna pay

us?

Let me tell you what they gonna

pay us.

They gonna pay you $2 an hour.

They gonna holler some kind of

apprenticeship deal or somethin'

like that.

Now, I mean, what else is that

gainin' you?

It's not gainin' you a thing.

You won't get anything.

They'll help you take...

You'll tear down your own homes.

It's a job, temporarily.

And then what you gonna do?

Where you gonna live?

You're not gonna live anywhere.

They not even in the process

of tryin' to tell you where you

gonna live.

All they talkin' about is

tearin' down Hunters Point.

>> How long you been in

San Francisco?

>> Oh, I've been in

San Francisco about 18 years,

ever since I was about

a year or 2 old.

>> And you live around here,

too.

>> Yeah.

>> In temporary housing or...

>> No, I stay in the projects.

It ain't no temporary housin' no

more -- they tearin' them down.

>> There used to be temporary

housing.

>> Mm-hmm.

>> Now it's permanent housing.

>> Ain't no more.

There ain't gonna be no place

when they get through.

>> Ain't that right?

>> We gonna be livin' out on the

streets.

>> Does it make you feel bad

because you...

>> Yeah, it make you feel bad.

Won't be no place to go.

We'd be livin' out here on the

streets in tents.

>> Where would you like to go,

if you could go?

What part of San Francisco

would you like to go?

>> I'd stay up here on top of

the hill.

>> You would?

>> Uh-huh.

>> Now, how long you been

livin' on top of the hill?

>> Ever since I been born.

>> And then this is part of

a redevelopment, also.

>> What do you mean, re...

You say "redevelopment,"

meaning...

>> Removal of Negroes.

>> Uh-huh. Yes. That's --

That's what I thought you meant.

>> In other words, a lot of the

Negroes who came because the

Japanese were pushed out now are

being pushed out, so...

>> Now being pushed out

themselves.

>> That's right.

>> And they think San Francisco

is reclaiming this...

>> That's right.

>> ...this property...

>> That's right.

>> ...to build it up,

which means Negroes have to go.

>> That's right.

>> Mm-hmm.

>> And in the...

>> Where are they going to go?

>> Well, they're going out

to Hunters Point and to the

Haight-Ashbury area and also

into Ocean View -- wherever they

can find the reasonable rents.

>> Yeah. Yeah.

>> South of Market

and all these other places,

wherever they can find cheap

rent, in other words...

>> Oh.

>> Going from one ghetto

to the other.

>> Yes. Yes.

This the Negro housing project,

in effect?

>> Yeah, as well as a few

Caucasians staying here,

you know.

>> Uh-huh.

Um, I know a lot about housing

projects in New York, but I'm

sure this doesn't differ at all.

>> No, houses there,

some of the same problems,

although, the building, the

exterior looks...

>> Well, the exterior looks

marvelous -- that's the whole

point, you know.

>> Yes.

>> But I know what goes on

inside.

Correct me if I'm wrong.

I'm sure that in the housing

projects...

I know the housing projects in

New York.

The kids despise 'em, you know.

Better housing in the ghetto

is simply not possible.

You can create, you can build a

few better plans, but you cannot

do anything about the moral and

psychological effects of being

in a ghetto.

>> This is it.

>> This -- this is the point.

Everybody living in those

housing projects is just as in

danger as ever before by all the

things a ghetto means.

By raising the kids in one of

those housing projects, I would

still have, at the front door,

or probably right next door,

in the housing projects, all the

things I was trying to escape.

That means such things as...

I mean, even from such things

as -- as dealing with insurance

companies if I want fire

insurance, you know, to the fact

that, um, in the playground,

my boy and my girl will be

exposed to the man who sells

narcotics, for example,

to a million forces where

are inevitably set in motion

when a people are despised.

And you can't pretend that

you're not despised if you are.

You were saying yesterday that

children can't be fooled.

I can be fooled, you know, and

be glad about, you know, having

a three-room, whatever it is,

some mashed potatoes, a terrace

overlooking a garage.

But my kid won't be because

my kids are being destroyed

by these fantastic apartments.

>> Now, this is the ILW housing

project, which will be

interracial.

The people who are renting it

now, 70 percent are Caucasian,

30 percent are Negro.

>> Mm-hmm.

>> Then above that would be

the Eichler homes and so forth.

Eichlers always let Negros buy,

if they had the money.

Although, their apartments,

I mean, their houses cost,

say, from $22,000 up to $32,000.

>> Yeah.

>> So, naturally, this

automatically...

>> Eliminates, yeah, Negroes.

>> ...eliminates a lot of

people.

>> I conclude that all this

has something to do with money.

The land has been reclaimed for

money, and that the people who

are putting up their houses

expect to make a profit, but it

seems to me that I'm attacking

what's called a profit motive.

There are some things more

important than profits.

I live in New York City, and

it's been turned into a desert,

really, for the same reason.

What is happening in

San Francisco now is that the

society made the assumption and

certainly acts on the assumption

that to make money is more

important than to have citizens.

You're paying too high a price

for this.

And it isn't only what it's

doing to Negro children,

which is, God knows, bad enough.

It's what it does to white

children, who grow up believing

that it is more important to

make a profit than it is to be a

man.

And that's the way the society

really operates.

I don't care what society says.

This is the way it operates.

And these are the goals it sets.

And these goals aren't worthy of

a man.

And adolescents know it.

>> Oh, you workin' out here?

>> No. I'm not.

>> Well, what has been some of

the -- what has been some of

your problems that you face

as a Negro in San Francisco?

>> Well, my main problem is, uh,

findin' a job.

Yesterday I talked to a guy

my wife knows that worked at a

fill-up station.

He been out of service 2 months

and he got two jobs.

>> Mm-hmm.

>> I been here 8 years, and I

worked about three steady jobs.

>> You ain't got no job now.

>> And, uh, I look every day,

just like he say he started out.

He looked maybe once or twice a

day, and he work at the fill-up

station and work longshoreman

work.

And he told me, from his own

mouth, who was on top.

He didn't come out and say

it just like I'm gonna say it.

But he come out and told me

that, uh, you got to know

somebody in San Francisco to get

somewhere.

And by knowin' somebody,

it's got to be somebody

with authority.

And nobody in San Francisco,

no colored man got no authority.

>> And I mean, no --

There are no Negro leaders in

San Francisco that you feel...

>> Well, there are a few.

There are a few.

>> Do you know any?

>> No, I don't know any, but the

ones that get up there...

The ones that get up there,

they don't want to help nobody.

>> No one has --

No one has ever helped you?

>> No, nobody with authority,

except my parole officer.

>> Well, even the least damaged

of those kids would have to...

...to put as mildly as can be

put at the moment, would have to

be a little sardonic about the

things he sees in television,

what the President says and, um,

all those movies about bein' a

good American and all that jazz.

And you look at this,

look over there, look up here.

And he would despise the people,

you know, who are able to have

such a tremendous gap between

their performance and their

profession.

But the more-damaged kids would

simply feel like blowing it up.

Simply feel like blowing it up.

In speaking only for myself,

you know, that I feel --

I feel a little sardonic.

I'm civilized, I think.

But there was a time in my life

when I would have felt just like

blowing it up.

What's more crucial,

what's more terrible is how

since one's mainly left alone

in terms of any help you can get

from the country, in this

effort, how do you get through

to these damaged kids?

And I don't know what I could

say which would make any sense

to them because, in fact,

this does not make any sense.

Now, with all of these beautiful

buildings, now, they're going to

be ringed in by hostile people.

>> That's right.

>> Just like they have in

New York.

>> Hostile and frightened

people, because they don't...

They walk down the street and

wonder why the first Negro boy

they see looks as them as though

he wants to kill them and,

if he gets the chance, tries.

And it's because he can't go to

Asia, you know, he can't...

It's because he can't --

He hasn't -- He has no --

He has no ground to stand here.

The cat said yesterday,

"I got no country.

I got no flag."

And it isn't because he's a born

paranoiac that he said that.

It's because of the performance

of the country for his 18 years

on Earth has proven that to him.

Now, how one manages to make

these people, these blind

people, begin to see...

Basically, that building...

It has absolutely no foundation.

And it really does not have

any foundation.

It's going to come down,

one way or another.

Either we will correct what's

wrong.

Or it'll be corrected for us.

>> And this is the...

>> What was that?

>> The Saint Mary's Cathedral.

This bombed building here?

>> Yeah.

>> I mean, not bombed, but, I

mean...fired.

>> Well, it looks bombed.

>> There was a fire.

But this is gonna be torn down.

But this will not be

the site of the cathedral.

They're going to change it.

>> Really is horrible to look

at.

>> Oh, yeah.

This was started one night.

They had --

Some of the kids were having a

dance in the downstairs.

Didn't take it very long.

It just gutted the whole thing.

But as a result, the

Catholic Church was able to

raise $15 million to build

another cathedral.

>> Some people know how to make

it.

I was raised a Christian,

you know.

My daddy and my mama were very

religious.

They knew that white Christians

were not Christians because of

the way they treated black

people.

And the Christian Church in this

country has never, in my

experience, never, as far as I

know, been Christian.

The record is much more than --

is much more than shameful.

The record in -- The record

proves that as we stand here

as of this moment, the

Christian Church is bankrupt.

There's not a single person I

could turn to, if I were tryin'

to deal with one of those boys

we were talkin' to yesterday.

If I tried to tell them to go to

church or even suggested the

name of Jesus Christ, he'd spit

in my face.

And it's not because he doesn't

like my face.

It's because of what white

Christians have done and do and

now deny.

All these churches are

absolutely meaningless.

They're almost blasphemous.

If they don't mean it, they

should -- you know, they should,

um, say so.

Christianity has become a kind

of social club.

You have to have a membership

card to get in, and black people

can't have a membership card.

Actually, Christianity, at the

moment, looks rather like that

church, that shell.

>> It's a God shop.

I mean, what...

>> Oh, the God shops.

I think the God shops --

I know the God shops are there

to console a whole lot of

desperate people, what we can

here call the failure of

Christianity, really, you know.

The people in the God shops

today, it gives them the only...

It's only one of the few places

they can go to find any way of

getting through their day, of

dealing with the landlord and,

um, pawnbroker and the children

and the whole powerful complex

of forces which bear you down

every day, when you no longer

accept this whole notion of

heaven later, you know,

concentration camp here.

Next to the Morning Star

Missionary Baptist Church.

>> Yes.

This is one of the real

little God shops.

>> Well, see, I've always

thought that Negro church is

singing and dancing and praying.

Maybe they were really quite

simple-minded and happier,

you know, than white people.

What goes on in those God shops,

you know, is exactly the thing

that's going on down in the

Muslim temples, but no one has

ever made that connection.

>> Off to our left here

is one Negro hotel, that's all.

>> The only Negro hotel here?

>> Yes.

>> It's called the

Booker T. Washington?

>> Yes.

>> Naturally.

This is a street that all

Negroes are born on, you know,

the street all Negroes have to

survive --

the Booker T. Washington, the

Baptist Church, and the mosque.

Mm-hmm.

There's really a great history,

you know, a great thing to be

summed up in that, if one could.

>> Looking at this street now,

the Booker T. Washington Hotel,

I mean, what comes to your mind

about, uh, some type of music

or some passage from the bible

that describes this?

>> Sing the Lord's song

in a strange land?

I don't know. I don't know.

I'm sure those guys across

the street can dance like, you

know, their white counterparts

can, and the reason they can is

because they, in a way, they

must.

It is...

It's got to come out somehow.

It's got to come out somehow,

you know.

And if the pressure is great

enough, it has to come out in a

certain kind of...

Negroes have great style.

I think this is true, even if it

sounds chauvinistic, and white

people don't have much style.

And one of the reasons

the Negroes have a certain style

is because they are aware of the

conditions of their lives.

They can't prove themselves

without it, you know.

And when a Negro laughs or tries

to make love or...

...or eats or dances,

it's a kind of total action.

I don't mean this the way white

liberals are gonna think I mean

it.

I don't mean that they're more

sensual, more primitive,

more spontaneous and all this

ethnic jazz.

I mean that they live --

they live on another level of

experience which doesn't allow

them as much room -- as much

room for make-believe as white

people have.

Any American black man knows

that there's something

that American white men...

They're in the grip of some

extraordinary sexual paranoia.

And they really are.

What that comes from is probably

historic from some other, you

know, some other time and place.

In any case, such a long and

terrible story and so

complicated that one couldn't

begin to discuss it except by

examining, if you like, you

know, such things.

When we read "Huckleberry Finn,"

we read William Faulkner, the

range between black and white

men in this country has always

been the most extraordinary.

And once....

There's something real in it and

a terrifying invention in it,

and it goes all the way back to

the first time any American

started writing, and it has

something to do with the

Indians.

If one could crack that nut,

really, open that can of beans,

if one could try to find out --

and this is something white

people have to do, Negroes can't

do it -- exactly what a Negro

means to a white man...

I don't mean what he means

in terms of signing petitions

and, you know, marching with

picket signs and all that jazz.

I mean, what he really means,

you know.

Why you're afraid of him.

That's what it comes to.

If one could begin to examine

that, one might then begin to be

able to deal with what is a

really quite simple matter,

relatively speaking.

That is to say, if one could

examine that, then the conundrum

of the housing situation in

San Francisco will not be a

conundrum because it is based on

that.

And all the lies Americans tell

themselves and all the evasions

that they give themselves are

based on some fantastic escape,

partly from Europe

and then from the Indians

and now, spectacularly, from me.

It's insane.

Well, white liberals think

of themselves as missionaries.

I had a kind of fight once with

a very well-known white liberal.

And I said, in the course

of my conversation, something

about "Mr. Charlie."

This man has been around for a

long, long time, and he said,

"Who's Mr. Charlie?"

And I was shocked that he didn't

know, you know, and I told him

who Mr. Charlie was.

I said, "You're Mr. Charlie.

All white men are Mr. Charlie."

But liberals have protected

themselves against this level of

experience because their

principal motive has so far been

as far as I can tell, a kind of

alleviation of or protection

of their own consciences.

They want to do something to

help Negroes because it makes

them feel better, but the price

that they paid for this kind of

effort is that they have never

discovered who a Negro is --

Not what, but who.

Only a liberal, for example,

could write the script to define

one.

No Negro could, you know.

Only a liberal can be offended,

as John Fischer at

Harper's Magazine is offended,

when, you know, when Negroes

make some unmistakable

indication that they're going --

that they don't want any more.

This is the record, you see.

They really think that, somehow,

the record of the Negro people's

survival in this country

is something on which they can

congratulate themselves.

And they don't know that

for every one man who survived,

20 perished, and that whatever

the Negroes manage to do here

was done against tremendous --

the tremendous abolition of the

power structure.

I don't mean there weren't some

white people who managed, you

know, but in the generality,

this is the way it's been.

>> Do you feel that the white

liberal, a lot of times, that

when things gets real tough,

that he can escape?

I mean, he can revert back

tomorrow.

>> Oh, the white liberal,

when things get tough...

A white woman told me a few

weeks ago, she had --

She had had the bad luck to be

sitting in the same room with

about 20 students who were, you

know, telling it like it is.

Sterling Brown was there, and,

uh, she was one of the few white

liberals in the room.

And what these kids were saying,

in effect, was, you know,

"White people don't know enough

about us to be able to help us.

You know, white people say one

thing and do another," and all

of this is absolutely true.

And she was terribly, terribly

hurt, literally hurt.

And she said, "I'm sure I done

more for Negroes than they've

ever done," and I got mad and I

said, "That's exactly what they

were saying -- they don't want

you to do anything for Negroes."

You know.

They want you to do it for you.

And she said, "Well, I'm not

willing to damage my child,"

she says, and I said,

"Well, then forget it."

After all, speaking for myself,

you know, it's kind of an

insult.

Here I am, you know, as they

say, "no visible scars."

I'm not -- I'm not isolated.

I got a family, you know...

>> Mm-hmm.

>> ...and a history.

And I got nieces and nephews.

I can't protect them, you know.

They're in tremendous danger

every hour that they live

just because they're black,

not because they're wicked,

you know.

And I mean this from the baby

niece to the oldest nephew,

who is soon gonna be 16.

Now, if this is the way that

they are, you know, and I know

that every time I leave my

nephew, I don't know what'll

happen to him by the time I see

him again, I mean, not only

inside but physically...

>> Mm-hmm.

>> How can you expect me to take

seriously somebody who says,

"I'm willing to fight for you,

but I can't afford to let...

I can't afford

to let my children be damaged."

And furthermore, how can I take

seriously somebody who doesn't

realize that their children

are being damaged by this,

by the continuation of this

system?

You can't, you know, you can't

serve, as they say, two masters.

You know, the liberal can't be

safe and heroic, too.

>> In other words, he wants it

to come full-face if gets behind

the safety zone.

>> Yes. That's right.

That's right.

He's with you but, um,

not when the going gets rough.

And though, really,

what I really mean about him

is that he doesn't...

If you can think of in those

terms and you don't see the

gravity of the situation, you

don't see that we are living

in a segregated society and this

does terrible things to my child

and does terrible things to your

child, too...

If you don't see that, then I

don't think you see anything.

And most of the liberals do not

see that.

One of the great American

illusions, one of the great

American necessities is to

believe that I, poor benighted

black man whom they saved

from...

...elephant-ridden jungles of

Africa and to whom they brought

the Bible...

...is still grateful for that.

And people say,

in many, many ways -- not only

in the South, all over this

country -- in effect, we should

be grateful, even slavery.

"They released you from that.

You're no longer dodging tsetse

flies in some backward country."

Well, I know this, and anyone

who's ever tried to live knows

this --

that what you say about somebody

else, you know, anybody else,

reveals you.

What I think of you as being

is dictated by my own

necessities, my own psychology,

my own, um, fears and desires.

I'm not describing you

when I talk about you.

I'm describing me.

Now here, in this country,

we've got something called

a nigger.

But it doesn't, in such terms,

I beg you to remark, exist in

any other country in the world.

We have invented the nigger.

I didn't invent him.

White people invented him.

I've always known --

I had to know by the time I was

17 years old that what you were

describing was not me and what

you were afraid of was not me.

It had to be something else.

You had invented it.

So it had to be something you

were afraid of.

You invested me with it.

Now, if that's so,

no matter what you've done to

me, I can say to you this.

And I mean it.

I know you can't do any more,

and I've got nothing to lose.

And I know, and I have always

known, you know, and really

always, that's probably agony.

I've always known that I'm not a

nigger.

But if I am not the nigger...

And if it's true that your

invention reveals you...

...then who is the nigger?

I am not the victim here.

I know one thing from another.

I was born, and I'm gonna be --

You know, I was born, I'm gonna

suffer, and I'm gonna die.

The only way you can get through

life is to know the worst things

about it.

I know that a person is more

important than anything else.

Anything else.

I learned this because

I've had to learn it.

But you still think, I gather,

that the nigger is necessary.

Well, he's unnecessary to me.

So he must be necessary to you.

And I give you your problem

back.

You're the nigger, baby.

It isn't me.

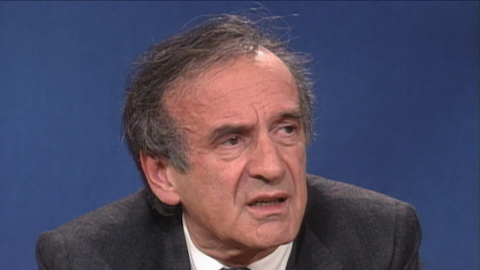

>> "Take This Hammer,"

filmed with James Baldwin in the

spring of 1963, was produced for

National Educational Television

by the KQED Film Unit,

San Francisco.

This is NET,

National Educational Television.