[dog barking]

[woman speaks in Navajo]

- [Voiceover] My grandmother told us things

our forefathers spoke of long ago.

That when our children had learned the white man's way

and spoke his language,

and had lost the old Navajo way of living,

the world would come to an end,

and they would all be destroyed

by big winds, water, and fire.

I believe now that this may happen.

Many things that were said in the past are coming true.

Our children have been taken away.

Much of our livestock has been taken away.

Now there are wars,

and our sons are being taken to fight those wars.

[aircraft whooshes]

[woman speaks in Navajo]

- [Voiceover] The white man has invented the airplane

and other great things.

Maybe it's because they are more educated

that they can do these things.

[woman speaks in Navajo]

Navajos have been unable to create new, modern inventions,

but our old way of life,

which the Navajo people cling to,

is changing fast.

Truly as the children go to school

and learn the white man's way of living and thinking,

the old way of life will end.

This is what my grandmother told me,

and that day is here now.

- [Children] I pledge allegiance to the flag

of the United States of America,

and to the republic, for which it stands,

one nation, under God, indivisible,

with liberty and justice for all.

♪ Oh Beautiful ♪

- [Narrator] This Navajo lies one mile

from the tribal cemetery at Window Rock, Arizona,

on the white man's side of the reservation mark.

The bar is called the Navajo Inn.

20 miles away is the town of Gallup, New Mexico,

near the foothills of Mount Taylor,

one of the four sacred mountains that the old Navajo world.

There is a bar like the Navajo Inn,

or a town something like Gallup,

for every Indian tribe in the United States.

They mark the edge of what is left

of more than 300 civilizations that were here

before the white man came.

[train clanking]

The Pueblo, the Cherokee, the Chickasaw, the Choctaw,

the Creek, the Seminole, the Iroquois, the Onida,

the Seneca, the Ottawa, the Padawahan, the Wyandon,

the Kikapoo, the Shawnee,

the Winnebago, the Delaware, the Peoria, the Miami,

the Mandan, the Blackfoot, the Cheyenne, the Kiowa,

the Sui, the Nespurse, the Yute, the Bannat,

the Comanche, the Zuni, the Apache, the Hoki,

the Shashon, the Washoe, the Salish, the Tilimon,

the Modock, the Pomo, the Miwalk, the Claman,

the Hema, the Yuma, the Moavae, the Navajo.

[train clanking fades]

[wind whooshes]

[woman speaks in Navajo]

- [Voiceover] Before there were any white men,

our forefathers lived and worked according

to their own ways.

There was plenty of grass then.

And many sunflowers, and lots of wild spinach.

We had our own God, as many of us still have.

[bells rattle]

The sun,

changing woman,

first man and first woman.

The Navajo people worked very hard then,

and they planted their corn according to their own thoughts.

[man speaks in Navajo]

- [Navajo Speaker] Things that had been put there.

What are [speaks in Navajo]?

Things that were put above.

[speaks Navajo], the sun.

[speaks Navajo], the moon.

[speaks Navajo], the stars.

[speaks Navajo], things that were put on earth.

[speaks Navajo], the living things on land.

[speaks Navajo], the plant.

[shovel clanks]

[speaks Navajo]

Things that were put

for the benefit of Navajo.

[horse snorts]

[speaks Navajo], Navajo ceremony.

[horse footsteps]

[speaks Navajo], beauty way ceremony.

[horse whinnies]

[speaks Navajo], enemy way ceremony.

[men speaking Navajo]

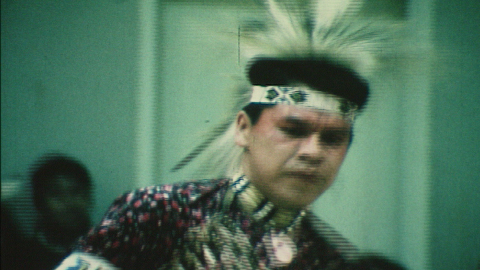

- [Narrator] The enemy way ceremony is performed

to heal and protect a Navajo who has become ill

because of contact with the ghost of a dead enemy.

It is a ritual to renew feelings of unity and solidarity

among the people,

as the Rattlestick is carried from one camp to another,

[man sings] families and clans reciprocate

with food, song, and prayer,

and their daughters perform in the squaw dance.

The enemy way is performed many times each summer

on the Navajo reservation.

[men converse in Navajo]

- [Man] [speaks Navajo], monster slayer,

who destroyed the enemies of the Navajo people,

whose father was the sun above,

who was born for the sun to kill all evil things,

is making his staff for me.

[Navajo chanting]

The staff of the extended bowstring,

the staff of many colored, beautiful cloth.

The staff of many colored jewels.

The staff of long life and happiness.

He who gazes on my enemy is making it for me.

He has made it for me, he has brought it here for me.

He has placed it in my hand.

He has rubbed it with sacred talon.

He has rubbed it with red oak.

With my elders, he is decorating it for me.

With men and women of my clan, he has decorated it for me.

With my children and with chiefs he now carries it away

for our people to see.

Once again, all has been restored to perfect beauty.

Once again, all on the earth has been restored

to perfect harmony.

According to the inner being of the earth,

changing woman, who is life giving,

who is life sustaining,

who is life restoring.

Here it is, where all life began.

And all parts are Navajo country rejoicing has returned,

long life, harmony, and beauty have been restored.

[men chanting]

[aircraft whooshes]

[woman speaks in foreign language]

- [Voiceover] Still there is the legend

of Nawilbehe, the winner from who the white man

was destined to come.

When he was defeated by the Navajo god,

with the help of the holy people, they vowed his revenge.

"You will become my slaves again," he said.

"And I will have power over your thinking."

This is the way the old people spoke

when there were yet few white men among us.

[woman speaks foreign language]

Now our children are becoming like the white man,

and our world is coming to an end.

My grandmother said that these things would come

to pass in eight generations.

Already five generations passed

since the Navajo people were at Fort Sumner.

[men faintly chanting]

- [Narrator] Fort Sumner, New Mexico, is an empty field now.

In 1864, it was the end of a 300 mile journey

for 6,000 Navajos.

The U.S. cavalry marched the defeated tribe

through the snow, along a trail that is now Route 66.

The Navajos had been starved into surrender

by an army of settlers led by kit Carson,

hired to retaliate for Navajo raids on whites.

The Navajos lost their land and were forced to relocate

on some of the worst land in the Southwest.

The long walk to Fort Sumner

has never been forgotten by the Navajos.

[woman speaks in Navajo]

- [Narrator] The Navajos lost their sheep and their corn.

They were stolen by their enemies, the Mexicans,

the Pueblos, the Apaches and the Yutes

who started making wars that lasted a long time.

Even their women and children were stolen.

Then the white man came and burned their crops

and cut down their orchards

and burned their homes until the Navajos had nothing left.

[man speaks Navajo]

[elder speaks in foreign language]

The people had to eat sunflower seeds and wild wheat.

[Elder speaks in foreign language]

[woman speaks in foreign language]

But many starved to death.

[woman speaks in foreign language]

The starvation continued until a white man came and said

the Navajos must go to Fort Defiance

or they would all be killed.

[woman speaks in foreign language]

They walked there, but many people, including children,

died on the way.

[woman speaks in foreign language]

Some were put in wagons and the rest started on foot

for Fort Sumner.

They would change places from time to time,

but there was never enough room in the wagons.

Many who were tired and sick were shot or left behind.

[woman speaks in foreign language]

[Elder speaks in foreign language]

Many good people died at Fort Sumner

of illnesses that were strange to men.

[Elder Two speaks in foreign language]

My mother was born at Fort Sumner.

My grandmother was 14 when she went there.

Seven people in her family died at Fort Sumner;

her mother, her father, her sisters, and her brother.

[man speaks Navajo]

Government leaders

told the people to be patient,

but there was continued unrest,

and pleas to return to their own country.

Finally, a commission of white men came from Washington.

[cars whooshing]

- [Narrator] Through the treaty commission

from Washington in 1868,

the great Navajo headman, Barboncito, had said,

"I hope to God you will not ask me to go

to any other country, except my own."

The Navajo knew that all Eastern tribes had been removed

from their countries

and transported or marched West of the Mississippi.

This resulted from

president Jackson's Indian Removal Act of 1830,

which created special Indian territory in the West.

After the Civil War, the Reconstruction Congress

decided that maintaining the Navajos at Fort Sumner

costs more than keeping them on their original home site.

Barboncito's plea coincided with government economy.

So on June 18th, 1868, the Navajos left Fort Sumner

in a column 10 miles long.

More than a month later,

the Indians arrived at their homeland.

Crops, orchards, and hogans had been destroyed

In the five years since Kit Carson and the settlers invaded,

more than 3,000 Navajos had died.

[woman speaking Navajo]

- [Narrator] The government man told the Navajos

they were now in the hands of a commissioner from Washington

who would tell them what to do.

The white man said that this would never change.

Now you have a great leader who will do

all the thinking for you,

because his thoughts are far better

than the Navajo's thoughts.

Your thoughts are not so good.

You are in the hands of a great leader.

Let him plan for you.

If you let him plan for you,

you will not go into poverty anymore.

[vehicle horns]

- [Narrator] In 1849, Congress transferred

the Bureau of Indian Affairs from the War Department

to the Department of Interior.

Indians were no longer defined as hostile foreign powers,

but as an internal problem.

Congress broke hundreds of treaties and agreements

and took Indian lands, Indian food supply

and tribal authority were destroyed.

[woman speaks Navajo]

- [Voiceover] Soon after the white man came among us,

it was decided that we should have policemen

to help keep the laws.

Policemen and leaders were chosen.

This was because of government people came from Washington.

- [Narrator] In 1876, the Santa Fe Railroad pushed

through the Navajo reservation.

Sections of land on each side of the tracks were taken,

whether Indians lived there or not.

[woman speaks Navajo]

- [Voiceover] From that time on many turned

to the ways of the white man,

but the older Navajos stayed with the ways and culture

in which they were brought up.

- [Narrator] From 1870 on, missionaries and BIA officials

converged on Indian reservations.

Indian religion was prohibited

and Christianity was introduced as a U.S. government policy.

[woman speaks Navajo]

- [Voiceover] Our leaders would go to Fort Defiance

and there white men from the government would tell them

that the Navajo people must learn

the white man's way of life to stay out of poverty.

- [Narrator] By the 1940s, the government moved

toward achieving the final solution of the Indian problem

by withdrawing its services

and initiating an assimilation policy

to relocate Indians in urban areas.

- [Woman] They used to tell us about this relocation program

over the radio from Gallup.

And they explained to us that we'll be getting

about $300 each at the time.

And they were going to pay our way.

So my husband thought that it was a pretty good deal.

I thought it was going to be kind of exciting,

but it was a disappointment to us,

the way we came out here.

And when we arrived here in Oakland,

they still had the train station up there

and they told us that somebody was going to be there

waiting for us to meet us,

to take us to this place

where we were going to be staying.

And there was nobody there

from the moment we step off that train we felt sick.

[whistle]

[faint traffic]

[whistle]

[soft bell rattle]

[whistle]

[soft bell rattle]

[traffic whoosh]

[whistle]

[low chatter]

[whistle]

[soft upbeat music]

[man sings]

[soft ball thud]

[quiet chatter]

[trainers squeak]

[basketball bounces]

[soft chatter]

[man chants]

[traditional drumbeat]

[early rock and roll music]

- [Man] Yeah, this came out on relocation

and he was going to welding school

and he never drank before he came out here.

But that's the only thing there was to do

because that's where the Indians were.

- [Woman] All this time, we've been wanting to go back home,

but it seems like we never could afford to go back.

Every year we plan to go back

but something always comes up.

[train horn]

[women speaks foreign language]

- [Voiceover] Then the government men said

"Now you are going to put your children in school,

you are no longer to live according to your own ways."

They told our people that our way of thinking was not good

because we went on raids and stole things,

and we're not educated.

- [Narrator] In 1928, the Miriam report

to Congress concluded that Indian education

had been a total failure.

In 1967, the Senate subcommittee

heard new testimony from Indians.

It's conclusions were spelled out

in the title of its published report:

"Indian Education a National Tragedy, a National Challenge."

I went to the Indian schools

when I was in the elementary schools.

And we learned about the wonderful government we had

in America and how we came

and discovered this beautiful land.

Back at home, we were hearing the BIA and-

- [Narrator] David Risling spoke for a group

of California Indians.

- On this hand, we'd learned that day

you waved the flag over here,

and we'd learn about all the wonderful treaties we made

and we uphold the treaties and then go back at home

and we hear that there's not one treaty

been upheld by our government.

And pretty soon we have to decide

do we believe the teacher, or do we believe our parents?

See? Then we have the conflict.

We start arguing with their parents.

And if the parent convinces us

we'd go back and argue with the teacher.

And you can, this is just an example

of how these frustrations come about.

They can come about in religion.

We go out there.

They say that your religion is all lousy over here

but then the Jewish people come over

and the Catholics and so on people come over.

That religion is all right, but ours is all in wrong.

So we didn't have this frustration that developed

within ourselves of who is right.

What is right?

[woman speaks in Navajo]

- [Voiceover] Now the end surely it's coming.

Many of our children are in school.

When they come home to us,

they speak in a language we can't understand.

Many are even discouraged

with the way we live and say,

"Why don't you get house?

I don't like this dirt floor."

- [Children] No, no.

[indistinct]

- All right, now at the end of "lo"

the tongue must be between the teeth.

- [Narrator] Intermountain School of Brigham City, Utah,

350 miles from the Navajo reservation

is the largest co-educational boarding school

operated by the BIA.

It is an all Navajo school of more than 2100 students,

12 years or older.

A former army hospital,

the school has been in operation since 1950.

According to an Intermountain press release,

the school's purpose is to prepare young Navajos

for an active role in modern society.

Conflicts that this transition causes are described

by the principal of Intermountain, Ms. Wilma Victor.

- I think that our students encounter many kinds

of conflicts in making the transition

from the Navajo culture to the dominant culture.

There are students who are going

into a time oriented schedule.

- [indistinct] I want you to dive into the water.

[school whistle]

The Navajo culture recognizes the passage of time

for a day, by morning, noon and evening.

And when we have a highly organized school program

that has periods which lasts from 11:23 to 11:59

this kind of thing is frustrating...

[man speaks foreign language]

- [Voiceover] I was born about four miles east

of Rough Rock at a place called Yale Point.

From the age of four to seven, I herded my mother's sheep.

We used to take them to the top of Black Mesa in the summer.

When I was seven,

I was sent away to the Chinle Boarding School.

Treated us pretty rough there.

There was severe discipline and bullying the boys by boys.

[metallic swirling]

- [Wilma Victor] The importance that our society places

upon acquiring private property causes a conflict.

- Their car is better than this one.

- [Teacher] Their car is better than this one.

- Their car is better than this one.

- [Wilma Victor] The Navajo emits primitive cultural pattern

was a part of a larger group in property ownership.

Things belonged to a family

and their families are extended families

not the immediate family.

[man speaks foreign language]

- [Voiceover] After two weeks in school,

I ran away with some other boys.

Pretty soon a policeman on a horse

came to take me back from Rough Rock.

[man speaks foreign language]

When I had run away six times,

they decided to send me to this school at Fort Apache,

220 miles away.

[man on PA system]

- [Narrator] Under an Intermountain description titled

"The Student Attitude," we find the following:

"The general outward appearance of these students

is one of quietness and calmness looking deeper.

In looking deeper, however, we find withdrawal

and suppression of intense feelings.

They are in a state of insecurity as to values

because of the need to satisfactorily blend the two cultures

in their lives.

They were accustomed to failure as an academic way of life.

They failed to understand the goals

of their educational program

and therefore lack motivation to achieve these goals.

- [Voiceover] After a year at Fort Apache,

I ran away from there too

with five other boys from Rough Rock.

I was home for about a week, herding sheep and horses.

Then one day as I started out

I saw the big policeman's horse outside the hogan.

I started off on foot up a wash that leaves to Black Mesa

but I heard the hoof beats of the horse behind me.

So after my 12 day journey, I was sent back to Fort Apache.

I was nine-years-old.

The policemen followed me

on a trail back to Chinle.

A truck was there from the Fort Apache

with other boys in it.

That night they hobbled our legs together

with handcuffs and made us sleep upstairs

in the policeman's house

so we wouldn't get away.

Next morning, handcuffs on our legs were tight and pinched.

As we pulled each other along, tied together,

they put us in the truck and took us back

through Indian Wells and Show Low to Fort Apache.

For punishment, the school supervisor

put us in the girl's dress

and made us carry logs round

and round the parade ground of the old fort.

We did this all day for two weeks.

- But this, a little dot of this

on your forehead, your nose, your cheeks, and your chin.

And this is your protective cream.

So that it's protecting your skin from the makeup.

It is a shame, I think sometimes

that we have to inform them of the fact

that there isn't individual obligation to oneself to achieve

because they feel much more strongly that every individual

must be ready to share everything that he has

with someone else.

We don't teach them that this is wrong

but we do try to motivate them

to personally achieve to their highest capability.

[train horn]

[woman speaking foreign language]

- [Voiceover] Because of the new way of thinking

our children are learning the big differences developing

between parents and children.

Often we do not understand each other

and cannot communicate our thoughts and ideas.

These are the things that are happening now.

This is truly the way it is.

[wind blows]

- [Narrator] Average age of death for Indians is 44 years.

For all other Americans it is 65.

Indian infant mortality is double

that of the rest of the nation.

Average Indian income is $1,500

with a 40% unemployment rate.

In a little more than 100 years

Government policy has reduced most Indians

to poverty and lethargy.

However, signs of Indian self-assertion

began to appear in the 1960s.

Stan Steiner, author of the book "The New Indians":

- [Steiner] Red Power are two words,

and all they mean is Indian control of Indian life,

Indian development, the way Indians [indistinct]

that's all Red Power means.

And the guys who thought it up

who were a bunch of young ex-Marine Corps,

college Red Indians

thought of those words,

just to put up the hair on the backs

of every BIA administrator, paternalist,

and missionary and everyone else.

But what they're talking about are not just scare words,

what they're talking about is Indian control of Indian life.

[chanting]

- [Voiceover] Diné was the Navajo word

for the people.

And in the Rough Rock, Arizona,

near the center of the Navajo Reservation,

the Bureau of Indian Affairs

turned over a school to the Diné Corporation.

The result is the Rough Rock Demonstration School.

A school which involves the entire community

and in which an all Navajo school board elected

by the community sets policy.

- Dorm parents.

- [Narrator] Dr. Robert Russell Jr.,

who is now Chancellor of the Navajo Community College

directed the school during its first two years

and then handed over the directorship

to a Navajo: Dillon Plater.

- [Dillon] Rough Rock in a way as a symbol

Whether we're trained or untrained,

but people think whether they're educated, uneducated,

we overemphasize, I think people being educated.

Maybe they are highly educated in the Navajo way of life.

[low chattering]

- [Narrator] The Rough Rock concept is simple.

Local control and community involvement.

The teaching of Navajo language and culture,

in addition to the ABCs.

Participation of parents in their children's education.

One of the first decisions of the Board

was the dormitories should be supervised by parents.

Anita Pfeiffer is Deputy Director of the School.

- [Anita] Many of the educators and administrators have felt

that the experts have always had to be consulted

concerning education of children.

But I think that our school has demonstrated

that parents are very well versed

in what their children should learn.

- [Narrator] The Rough Rock School Board meets weekly

and the parents come together once a month.

Here, Yazzie Begay Vice Chairman of the School Board

and Anita Pfeiffer meet with parents

to explain school curriculum.

A Navajo teacher translates

for the benefit of white staff members.

[man speaking Navajo]

- [Translator] Here at the school

we want children to learn not only the English way

but the Navajo way of life.

We want them to learn to read and write.

We want them to learn the kinship system

that exists in our Navajo tribe.

- [Teacher] This is called [speaking Navajo].

[children repeat Navajo word]

Which way does it always face?

[Teacher and students speak Navajo]

- [Teacher] Towards the east,

it always faces towards the rising sun.

Willoki, would you read, please?

- [Student] In years gone by parents

trained their children to get up early in the morning.

They were told to run to the East as best as they can go.

- [Narrator] Classes at Rough Rock are ungraded

and children learn at their own rate.

- [Man] There are many schools among us.

There is your government schools,

you BI schools, some of them-

- [Anita] And some of the schools on the reservation,

the children are punished because they speak Navajo.

We feel that if the school approves

of the child speaking his own language,

that the child gets the idea

that there is something worthwhile

about his language and his culture.

[Teacher speaking Navajo]

- [Teacher] Say that.

[Student repeats in Navajo]

- [Teacher] Again. [Teacher and student speak in Navajo]

- [Teacher] No, you're saying [speaks Navajo]

You're supposed to say [speaks Navajo].

[Student speaks Navajo]

- [Student] I don't want them.

- [Teacher] These are sunflower seeds.

- Are they real?

- [Teacher] Yes, they're real.

Would you like one?

[children chatter indistinctly]

- [Teacher] Okay. Now I'm going to go out

and find some plants.

And we're going to press the plants so that they'll dry out.

And then we can put them up on boards like these over here.

Okay.

- [Student] Yeah.

- [Teacher] All right.

Let's listen carefully.

Make sure everybody understands now in Navajo.

[woman speaks in Navajo]

- [Anita] Often too, is that the children can learn

about both cultures.

They don't have to choose.

A lot of young Navajo children

don't know about their own culture.

Don't know about the Navajo history.

The myths and legends are told during the winter season.

And this is all forgotten by the children

because they're in school.

At Rough Rock we have storytellers

who come to the dormitories

and tell the children, the legends and myths.

- [Narrator] The legends are also recorded on tape

and published in books

at Rough Rock's Navajo Cultural Identification Center.

The books are widely used in many schools.

A written history of the Navajo people

in English and Navajo is now in progress.

- [Man] This is storytellers Sam Willie.

He's taping.

[Sam speaks in Navajo]

The subject is [mans speaks Navajo]

which is the the Navajo blessing way.

- [Man] We wash the main source of Navajo ceremonial way.

A long time ago.

According to the Navajo, by word of mouth,

in the creation,

is a story about white corn.

It pertains to the birth

of the young children.

And the myth goes back to the sun as a source

and a creation of the first man and the woman.

It was the school board's idea that there should be books

on Navajo legends, and Navajo history

to have something written about Navajo leaders

which Navajo children can read and look up to.

- [Teacher] Let's see if you can remember

some of the leader.

Name one.

- [Student] Narbona.

- [Teacher] Narbona.

Ganado Mucho,

We will be studying them and see what

they did in leading our people over Fort Sumner,

what they said, what they did, how they helped our people.

We will be studying them.

- [Narrator] Rough Rock serves some 100 families

in a 2000 square mile area,

more than half of the 368 students board at the school

because of impossible road conditions

on the reservation.

In spite of the distances, Rough Rock seeks

maximum community involvement.

The school provides jobs for as many local people as it can

and offers craft programs and adult education classes.

A community development project

offers milk for lambs and hay.

- [Man] If a sheep are starting out there that no other way

for the community to get help or assistance,

then if the school has any resources at all

it helps.

Another thing is they wood hauling project

from the poor families can come over here

who don't have transportation

and they can haul wood from here.

- [Narrator] Rough Rock provides summer school programs

so the children can work at home part of the time

and still keep in touch with their school work.

- [Teacher] On this side of the clock,

we say...

What?

Past. On this side of the clock, we say who?

[children murmur]

All right, you have your conjunction "and"

where does that go?

Right.

Okay.

Now we go on, we draw our line

which shows is what is your compound verb.

- [Student] There.

- [Teacher] Right?

What is, what is the verb?

- Glared and...

- [Man] Stood and glared, right?

- Stood and glared.

- [Teacher] Okay, all right.

Two subjects, two verbs.

[woman speaks Navajo]

- [Woman] How do you spell elephant?

- [Students] E-L-E-P-P-H-A-N-T

30, 40, 50, 60, 70...

[man chanting]

- [Narrator] The purpose of Rough Rocks by cultural approach

is to help Navajos to live comfortably in both worlds.

Betty Daley, one of 12 bilingual secretaries

trained by the school lives in a hogan nearby.

[heeled footsteps]

[people murmuring]

- [Anita] Many of the students who go away to school

come home and feel very uncomfortable

with their own families.

And some of them because of their two years in college

feel very superior,

but still, they don't really have a place

in the Navajo society or the Anglo society.

And they're just sort of misfits.

They go home and don't know how to make fry bread

or how to cook mutton - very little things.

How do you dry a sheepskin?

There's a proper way to do it.

If you don't know how to do it that exact way

then you're not, you're not a good Navajo.

That's really what we're doing here at Rough Rock.

The students can go home to their relatives

and operate like a Navajo, go to a middle-class home

and operate like a middle-class Anglo.

And if they know how to switch between the two, no problem.

The best part is that many of the parents are interested

in what their children are learning.

And many of them have expressed the wish

that they had this kind of a school when they grew up.

[women singing in Navajo]

- [Teacher] All right, let's go on.

- [Child] They made waterbeds of goatskin.

These could be carried on horseback.

After they learned the ways that the white man

they stopped using their grinding stone.

They bought flour and sugar,

lard, coffee at the trading post.

- [Teacher] Okay, it says after they learned the ways

of the white man they stopped using their grinding stones.

Is that true?

- [Students] No.

- [Teacher] No, we still have them, don't we?

[aircraft whooshes]

[man speaking Navajo]

- [Man] The things by which the Navajo was created.

[speaking Navajo], wood.

[speaking Navajo], fire.

[speaking Navajo], water.

[ceramic clink]

[speaking Navajo], Navajo food.

[baby cries]

[people murmur lowly]

[thunder]

[echoing clang]

[man chants]

- [Narrator] Mrs. Husba Charlie

lives near the Rough Rock school

She is one of 40,000 Navajos

who does not understand English.

Rough Rock staff member Teddy Draper

visits twice a year with many families

in the school district

to explain what is going on in the world.

This particular day, July 20th, 1968...

- Put one man on the moon.

and I'm going to ask her what they think about it.

And then...

[radio static] [indistinct talking on radio]

[beep]

[radio static] [indistinct talking on radio]

[man speaks Navajo]

[woman speaks Navajo]

- [Voiceover] The Navajo people lived

in a holy way when I was young.

And many things were kept sacred.

Today people claim there is nothing on the moon.

But when I was young,

men said there was something inside it.

I don't think men were supposed to go there.

[woman speaks Navajo]

The Navajo believe it rocks Earth,

sun, stars, moon.

Everything is a living thing.

They're careful about a lot of things because they believe

that if you're not careful, it's going to harm you.

But they're living.

[man on radio] [radio static]

- [Narrator] This cemetery is near Tuba City

on the Navajo reservation.

And many of its graves,

mark children who have succumb to malnutrition.

- [Man] Yeah, a lunar walk. [man laughs]

- [Narrator] Mr. and Mrs. Bilagody

who exist on welfare have lost a daughter, Christine.

- She didn't have enough of better food.

Would we have a better food,

it would have been different.

- [Narrator] Dr. Alberto was presently

attending another Bilagody child, Nathaniel,

for the same reason.

- [Dr.] When Christina Bilagody reached the hospital

she received the most up to date medical care

that's available.

Medically speaking, this death was not avoidable.

From a social point of view or a society point of view?

I feel like it wasn't an avoidable death.

When Nathaniel Bilagody was admitted here

at two weeks of age,

his birth weight was six pounds and four inches.

At the time of admission

he weighed scarcely four pounds, 15 ounces.

He was already very severely malnourished.

[baby cries]

He may not ever develop a normal growth pattern.

This very [indistinct] has all been inadequate.

- [Narrator] John Site is Director of Welfare

for the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Tuba City.

- [John] Lack of education started all of it.

There are all resources available to her.

Why she does not choose to avail herself

of these is an individual matter.

If a family of four has an income of $200 a month,

according to the current state standards,

based on an ATW formula

they would have sufficient income to meet their needs.

And a good manager can do exceptionally well.

A poor manager has problems.

- The problem, I really feel that a guarantee...

- [Narrator] John Aman is Welfare Officer

for the State of Arizona.

- [John] To me, it seems like a dumping ground

for surplus foods that the government buys

and then the distributors as a token gesture of mercy.

It's like a band-aid put on a big open gaping wounds.

Many people don't get their commodities

because they don't have transportation.

Many will walk miles to the warehouse

or to the pickup station and just wait there all day

'till they find someone that will take them back.

I think that I would, I would lose a certain amount

of my dignity in a sense, if I were as a Navajo,

picking up food from Washing Dawn, as they call it.

And Navajo are basically trusting,

they think this is a whole food.

This is, this comes from Washington Dawn.

This is what is given to them.

When someone's hungry

he has to go through all the rigamarole of eligibility.

Red tape, going from one agency to another.

If he has one extra child

or one lesser child that he gets less or more,

this is not, this is not honesty.

This is not humanism.

It's it has nothing to do with ethics.

It's cruel [indistinct] to me.

To me, it's another way of skirting the real issue.

The real issue of poverty and hunger.

[radio beep]

- [Houston] Columbia, this is Houston,

we'd like you to cycle [indistinct]

and fly your hydrogen tank number one.

And L-O-S [indistinct] orbit

is one, one, one, one-niner, three one.

[beeping]

Correct and make that for the next door.

But Columbia, this is Houston

- [Man On Radio] when you lose lock on us,

we request Omni-Delta.

- [Man 2 On Radio] That's okay.

- [Man 3 On Radio] That's good.

[person speaks Navajo]

- [Voiceover] People should be told not to go there.

They are doing the wrong thing.

This is why the world is in the situation it is.

And why we have no rain or vegetation.

[radio beep]

- [NASA] [indistinct] this is Houston.

F21160 [indistinct] ...

- [Neil Armstrong] ...depressed in the surface

about one or two inches

Although the surface appears to be

very, very fine grained as you get close to it.

It's almost like a powder.

[indistinct] is very fine.

The surface is fine and powdery.

- [Jack] The land is eroding away at a very rapid rate.

The vegetation that we see for thousands of acres-

- [Narrator] Jack Crowder, pilot and contractor,

builds dams for livestock.

- [Jack] Hardly any edible plants left.

There's an awful lot of wind erosion.

And, whenever it rains, there's nothing to hold the soil.

We get over this hogan you will see

this finger-like head cuts coming down the main canyon.

A little at a time, they're cutting back

until they reach the rock on the railings.

If you knew how long this took, say it took a hundred years,

you could predict the day

when there won't be any soil on the Black Mesa

unless they start managing the rain and get some vegetation,

every bit of it will be gone.

- [NASA] we can see you coming down the ladder now.

- [Broadcaster] On this day, July 20th, 1969,

Neil Armstrong, an American astronaut

becomes the first man to set foot

on the surface of the moon.

- [Neil Armstrong] That's one small step for man,

one giant leap for mankind.

- [Man] Unofficial time on the first step,

1092420.

- [Neil Armstrong] Sides of my boot.

- [NASA] Neil, this is Houston, we're copying.

- [Neil Armstrong] Here in the shadow

and a little hard for me to see that I have good footing.

I'll work my way over into the sunlight here

without looking directly-

- [Man] A lot of people are confusing

[indistinct] between culture.

White culture just came and a lot of them just got trapped.

It's just doesn't matter anymore, you know.

- [Neil Armstrong] Hey, you got it.

Beautiful. - [Man] Beautiful.

[indistinct]

- Let me tell you one thing, you know

you learn to be quiet like in a boarding school.

You come not knowing the English.

You afraid, you be afraid to speak in English

because you know, you'd be missing words.

You know, that you won't put the sentence

the way it should be.

You have feeling that you want to express with your teacher

but you don't know how to say, how to express,

because there's no nobody else in there.

That's a doubt, who'll understand you.

So, you know, you learn to be quiet.

I learned to be quiet, you know,

when I got into boarding school [indistinct].

[woman speaking Navajo]

- [Voice] The old teaching has stopped.

And now the Navajo do not know who they are.

In the old way, the Holy way,

people listened to each other's problems, but not anymore.

They spoke of many things, but not of going to the moon.

Many young people are losing the Navajo way.

I wish they still learn about these things.

[woman speaks Navajo]

- [Man] [speaks Navajo],

physical bodies.

[speaks Navajo], the soul.

[speaks Navajo], the spirit

[speaks Navajo], the thought.

[speaks Navajo],

the sound of the voice.

[children chanting]

- [Teacher] Good morning.

- [Teacher And Students] How are you?

Very well, thank you.

[Teacher speaks Navajo]

[Teacher And Students] Very well, thank you.

- [Teacher] Good morning.

- Good morning. - Good morning.

- [Teacher] How are you?

- How are you?

- Marianne McCurtain.

- [Woman] How are you?

- [Teacher] Good morning.

[woman laughs] - Good morning.

- [Man] Margaret Paul.

Sally Dick.

Otto T Draper.

- [Narrator] The month before the first American

landed on the moon

another first occurred on an Indian reservation

in a remote part of Arizona

At Rough Rock, the first graduation

at an Indian controlled school.

- [Man] Jimmy Sells.

[indistinct].

- [Narrator] Senator Edward Kennedy

addressed the graduating class.

- [Senator] After years of deportation

and degrading captivity in government boarding schools,

the Navajos had taken the first important step

towards regaining control over their educational destiny

and in, so doing Rough Rock stands as a symbol

for the improvement and the liberation

of Indian education throughout the nation.

[Barry speaks Navajo]

[children talk]

- [Man] I've been thinking if I write about Rough Rock

that I would write a piece called Laughter on the Mesa.

'Cause this is the first time I've ever been

to a Navajo school where during the class kids laugh.

I think if it's possible for kids to enjoy school,

Dillon Platero and the rest of the people

who are running this school

are establishing a basis where kids will really come back

with fond memories of having been educated in their own way.

That's Navajo power.

The Rough Rock is an example of it.

- [Man] In the past years, the hopes of Indians and others

have been woefully disappointed.

Every four years with the new administration

there is a peak period

of feeling that things are going to move forward rapidly

with boldness and with success

but we've never realized this kind of progress.

The lesson that one learns from Rough Rock

and from Navajo Community College

is that Indians have the ability

and the desire to control their destiny.

And I think that if we begin to eliminate the programs

and the policies that are founded

on the erroneous principle

that the Indian going to cease to be an Indian

and that he's going to melt in the melting pot,

I think we will take a long step towards success.

The Indian people must direct their own affairs

and determine their own educational objectives

and how these shall be met.

Indian people have got to do the talking.

[children chatter]

[bus door shuts]

- [Barry] Our students can perform right along

with any other student.

I don't think we need to take a backseat to in this area

but I think there is some reluctance on the part

of these agencies that are involved in Navajo education

so that the Rough Rock program is in a way threatening

but rather than think about their own person,

I think that we should think about the children.

[children sing]

♪ Where are you? ♪

♪ Here I am, here I am ♪

♪ How do you do? ♪

[whoosh]

[children sing]

♪ Where are you? ♪

♪ Here I am, here I am ♪

♪ How do you do? ♪

[train bell] [children sing]

♪ Where are you? ♪

♪ Here I am, here I am ♪

♪ How do you do? ♪

[children sing]

♪ Where are you? ♪

♪ Here I am, here I am ♪

♪ How do you do? ♪

[children sing]

♪ Where are you? ♪

♪ Here I am, here I am ♪

♪ How do you do? ♪

[children sing]

♪ Where are you? ♪

♪ Here I am ♪

♪ How do you do? ♪

[children sing]