By Nida Khan

By Nida Khan

This content contains scenes that may be too sensitive for some viewers.

“From the moment we stepped off the train, we felt sick,” recounted a Navajo woman in the film The Long Walk as she discussed forced relocation. “All this time we wanted to go back home but could never afford to go back. Every year we plan, but something always comes up.”

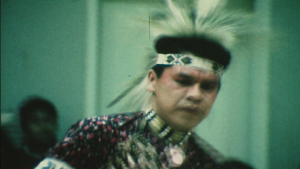

What she was painfully relating was the withdrawal of government services and the relocation of Native Americans to urban areas in the 1950s. This is one of many subjects covered in The Long Walk. Tracing the Navajos’ forced migrations and other maltreatment by white Americans in the 19th century, this film takes a direct look at the cruelty inflicted upon the Navajo, and the people’s determination to maintain their traditions and their heritage.

The Long Walk is one of 50 films featured in the Legacy Archive Project Exploring Hate: Antisemitism, Racism and Extremism. At a time when the United States is striving to reconcile its difficult past with hope for a better future, the Legacy Archive Project is a space where everyone can go to learn, increase their understanding of historical events, and apply the lessons of the past for the present.

Watch a clip:

Recently, the Texas state senate passed a bill that would allow public schools to avoid vital subjects like the Civil Rights Movement, women’s suffrage – and Native American history. Senate Bill 3 (SB3) is just one of many advanced by legislatures in numerous states that are effectively rewriting history by removing aspects and incidents that reflect badly on the United States. While many aspects of our history are indeed horrendous, ugly and difficult to absorb, to erase them is to delete the experience of marginalized communities, in effect silencing them. Discriminatory practices and policies, outright murder and land theft — these laid the foundation for the present-day circumstances of ethnic minorities that form an underclass in America.

It’s no coincidence that bills like SB3 are simultaneously attacking Native history, the study of the women’s suffrage movement, and the Civil Rights Movement. To achieve any progress in historically disenfranchised communities has always involved struggle, and often the movements have become intertwined. There are examples everywhere even today, as demands for criminal justice reform and women’s right to choose are voiced in intersectional demonstrations.

In 2020, when antiracism and anti-police brutality protests broke out in unprecedented numbers across the country, a diverse coalition raised their voices in unison. In Minneapolis, where the murder of George Floyd by police sparked demonstrations, there was a noticeable Indigenous presence, including protesters who flew the flag of the American Indian Movement. Like other communities of color, Native Americans have often been victims of excessive and abusive policing tactics. It is why they were active during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, and why they continue to be active today.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States, the Native American community suffered greatly. The Indigenous population suffered more than 3.5 times the infection rate of white Americans, more than four times the hospitalization rate, and a significantly higher mortality rate. Healthcare disparities and a lack of resources contributed to these higher numbers and tragic outcomes. But Indigenous communities organized and fought back, as they were accustomed to do in the past. Native Americans now have the highest vaccination rate in America, according to the CDC. It is just one more example of their perseverance in the face of adversity.

Whether it was the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Dawes Act of 1887, or forced relocations and assimilation in the 20th century, the dispossession of Native lands has had catastrophic consequences for Indigenous communities. The Long Walk examines the history of the Navajo Nation through the eyes and perspectives of its people. As the Indigenous continue to advocate for recognition and a return of what was once stolen from them, this film provides great context and insight.

In 2020, when President Donald Trump went to Mt. Rushmore to deliver a divisive speech, activists took the opportunity to draw attention to the Land Back movement. For decades, Native Americans have been pushing to reclaim millions of acres of land in the Black Hills of South Dakota. The U.S. Supreme Court actually upheld the tribal claim 40 years ago, but only ordered restitution. Tribal leaders rejected the money and insisted on reclaiming the land. The struggle for reclamation of ancestral land, taken in violation of treaties, continues today.

Historical context is a key to understanding present-day inequities and the effort to bring about change. The Legacy Archive Project Exploring Hate: Antisemitism, Racism and Extremism examines ways in which groups of people have been subjugated, disenfranchised and discriminated against, as well as how these communities have organized and fought back.

In 1977, participants in the United Nations International Conference on Discrimination against Indigenous Populations in the Americas proposed that Indigenous Peoples’ Day replace Columbus Day. As an increasing number of states and localities make the shift, a more accurate portrayal of history emerges. In Canada earlier this year, hundreds of unmarked burial sites of school children were discovered. Canada has now observed its first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, honoring victims of its residential schools, which sought to forcefully assimilate Indigenous children.

While official recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ Day and a National Day for Truth and Reconciliation are important and necessary symbolic steps, the Indigenous still face a very real threat from forces attempting to rewrite history. In the United States, mechanisms designed to alter school curriculums are blatantly erasing Native experience and concealing the truth about America’s founding. It is why efforts to push back have taken on renewed spirit. As Land Back movements are galvanized in South Dakota and elsewhere, and police reform movements from Minneapolis to the Bay Area take on a new sense of urgency, Indigenous peoples are themselves a living, surviving reminder of the very long walk that they have endured.

The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.