[jaunty music]

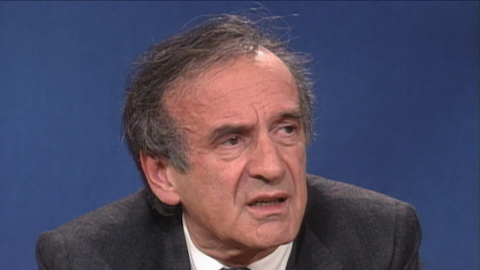

- I'm Richard Heffner, your host on the "Open Mind."

I had the honor and the pleasure some months back

in talking with today's guest on

my other program, "From The Editor's Desk."

There, however, I had to share him with two colleagues

and three commercial breaks,

and I've so much looked forward to this day

when for much longer,

I might intellectually visit with Elie Wiesel,

the distinguished teacher, philosopher,

historian of the Holocaust.

Mostly I want to ask him about indifference,

about the carelessness that informs so much

of human history, human behavior.

On "The Editor's Desk,"

Elie Wiesel said that at the end of the World War II

in Paris in 1945,

for him after Auschwitz and Buchenwald,

he had asked himself the question, "Why?"

Well, I asked him whether by now

he has discovered the answer, his reply,

"No. I confessed to you that all the questions

that I had asked then, they are still open today.

I haven't found any answer.

I found components to answers.

I found, for instance,

that what allowed the situation of absolute cruelty

to develop was the indifference of so many people.

They let it happen.

There were a few maniacs of murder

and all around there were others who knew

and somehow let it happen.

Therefore, in most of my books,

I denounce indifference to evil

as much as I tried to denounce evil."

And that's the subject Mr. Wiesel,

that I'd really like to begin with today

and ask whether that was a comment

about the nature of human nature.

- Certain times, of course, some people need indifference.

- [Richard] What do you mean need?

- In order to go on living.

A person who is always sensitive,

always responding, always listening,

always ready to receive someone else's pain.

How can one live?

Indifference then is close to forgetting?

One must forget that we die.

If not, he wouldn't live.

However, there is so much forgetfulness

and so much indifference today that he must fight it.

We must fight for the sake of our own future.

Is this the nature of human beings?

It's part of the nature.

- It's so interesting to me that you should take

such a generous position, as indeed you always have,

but it is not a position seemingly of anger. How come?

- Oh, if I had had anger,

I think I would've been crushed by it.

It's like hate.

Hate destroys the hater much more than the hated.

There were so many reasons after the war

and since the war for people such as myself

to develop anger and to arm anger,

that it makes no sense.

- It makes no sense, but it is human.

- It's also human to fight anger.

So I have to choose between two options of humanity.

And I would rather choose this one.

Mind you, if I had felt that it would lead me somewhere,

it would give me an answer,

it would give humanity an answer, maybe I would've tried it,

but maybe it's because of my own weakness.

I was afraid of anger, but I never felt hate.

Not have I ever felt real anger.

- In "The Fifth Son," the newest volume, the newest novel,

I should say, the newest volume actually

is the compilation of "Night," "Dawn,"

and "Day" that the new book you put out.

In the novel, "The Fifth Son,"

there seems also to be that conflict.

I shouldn't say also, you haven't stated a conflict,

but there seemed to be a conflict.

- Well, there is a conflict.

Of course there is a conflict.

After the war,

the Germans were afraid.

They were not afraid of the Americans,

nor were they afraid of the French.

Of the Russians? Yes.

But above all, they were afraid of the Jews.

Somehow they felt that the Jews would come back and avenge.

And avenge the blood that was shed and it didn't happen.

It didn't happen. There were Jews in Germany,

in the DP camps, and there were acts of vengeance.

There was not no killing.

I remembered 1945.

When the war ended for me, April 11,

the Americans came in into Buchenwald.

I was terribly weak and sick and alone

and desperate and numb.

We hadn't eaten for so many days.

And for since April 5th, we were close to death,

literally because the Germans

were trying to evacuate the camp

and they would take out 10,000 people a day,

ship them off to the unknown.

And for some reason, really, I don't know why we,

the children's block remained behind.

And then the Americans came in and I remember

there were some Russian war prisoners.

They seized American Jeeps

and they ran into the neighboring town of Weimar.

And they did commit acts of vengeance.

As for my friends and myself, you know,

there were the Americans there.

I'd never forget these Americans

'cause I remember there were some black soldiers

and these were the first black soldiers

I had seen in my whole life.

And they were crying.

They were crying with such anger.

They were angry at the killers, much more than we were.

And they were throwing whatever they had. You know,

the K rations and bread and chocolate.

And we didn't know what they were.

What we wanted to do first before eating

is to have a religious service

and we had a religious service.

So instead of going and commit acts of anger and wrath

and bloodshed,

we prayed to a God who had abandoned us.

To this day, I don't understand why we did it.

- [Richard] Do you understand why God abandoned you?

- Oh no, of course we don't, I won't understand it.

I refuse to understand it.

And....

- [Richard] Why do you say you refused to understand it?

- There can be no reason.

If there is a reason, it's the wrong one.

- [Richard] You mean then that God did not abandon?

- Oh, I think he did.

I don't know why.

- In terms then of what you felt

and what you say so many Jews in the camps did feel,

how do you relate that to the attitudes

of contemporary Israel, to the Palestinians

for instance?

To people Israel considers her enemies?

- I was in Israel in 67 during the war.

I was young, a journalist, and I felt I had to be there.

I felt I had to be there

because the three weeks preceding the war,

maybe you remember were of such intensity.

We were all convinced that Israel would lose the war.

And therefore I went there.

And I will not forget.

I don't want to forget the human way

in which these Israeli soldiers treated the enemies.

They were crying.

I was in the desert and I saw how Israeli soldiers

gave their water to the Egyptians.

There is no hate in the Israeli soldier.

- [Richard] That was true in 1967.

Do you think it's true today?

- I think it's true today as well. It's some exceptions.

Unfortunately, there is now a small segment in Israel,

which is racist, which embarrasses me as a Jew.

I don't know whether they and I belong to the same people,

whether they and I claim kinship with the same tradition.

Judaism cannot be racist.

I believe the Jewish tradition is one of compassion,

must be one of compassion, but it's not Israel.

It's a small segment in Israel.

Israel as such, I believe is still,

is still human and humanely inspired.

- Mr. Wiesel there are reports that that segment,

though small, is getting larger and larger.

Do you feel that those reports are accurate though?

Hateful perhaps, but accurate?

- I don't know. I have not been to Israel for years.

So I don't know, I hope they are not.

And if they are, I hope that they are only a passing mood.

It would be a terrible blow, to not only to Israel

as the political entity that it is,

but to the history of Israel to have lived 3,500 years

and to come to that conclusion

that we have to try racism

and there is no other option than violence?

And to see in everyone else in enemy?

That is not Judaism.

- Do you think that perhaps Israel's relation

to the United States might be fostering

that in so many of our own travails

there have been so many people who have said

the Israelis could do it.

The Israeli soldiers could do this or that.

They would know how to handle the enemy.

- How do they handle the enemy?

What do the Americans think that Israelis do

when they handle the enemy?

There is an occupation of territories

and I'm always on the side of the humbled,

but I'm a traumatized person for the reasons

that you mention yourself. I'm traumatized.

I cannot, I cannot believe that Israeli occupier

is just another occupier.

Impossible.

- But when you say that you're always on the side

of the humble, do you mean on the side of the weak?

- On the side of the defeated. Of the victim.

- Wouldn't, then, if someone were watching us today

and Elie Wiesel says he is on the side of the defeated,

the victim, say I can admire,

I can embrace this man for the beauty in him

for his feelings,

but I must turn for all many practical reasons

to another philosophy to survive.

- Oh, I'm also for survival.

- [Richard] You did survive.

- Not only I did,

my personally doesn't really matter why I survived.

I don't know.

I didn't do anything for that.

I swear to you. I was too young. I was too weak.

I didn't know why.

I was never a man of initiative.

I survived by chance,

but because I survived by chance,

I have to give a meaning to my survival.

That's really what I believe in.

I don't think I should speak about the miracle

because there was no miracle.

If God performed the miracle in saving some,

that means he refused to perform miracles

in the condemning the others.

I don't go for that.

So I am for surviving.

I want the Jewish people to survive

and I want all people to survive.

Now I am naive in thinking that it's possible

when it's possible to live in a messianic era.

When people believe happily,

not the expense of someone else's unhappiness,

but at least you must try.

- You say that is possible.

And you smile.

- I smile because you and I

belong to the prophetic tradition.

We have a past, which goes very Isaiah and Jeremiah.

And these were prophets. These were poets.

Jeremiah was also a politician,

great politician, suffered for it.

But what we remember is not his politics.

We remember his poetry.

And that goes for Isaiah and for Habakkuk

and all of the other prophets.

We claim that tradition is our own. As our memory.

Here is a tradition that becomes our memory.

How can I not believe in it?

- But that memory now is fostered and protected

and defended and expanded too.

Let does not forget that.

By those who have a somewhat different approach,

considerably a different approach from your own in Israel.

- I know. That's not new. You know?

We had zealots some 2000 years ago in Jerusalem

and they were a catastrophe.

They brought a catastrophe.

Jerusalem was destroyed because of those zealots.

I claim kinship with Yohanan ben Zakkai

who left Jerusalem

because he wanted to establish schools

and he did establish schools.

And he was the pillar on which the Talmud has been built

and which kept us alive for 2000 years.

Now, again,

that doesn't mean that I think that the Jewish people

should simply now lead a Talmud and not have an army.

They have an army, they need an army,

because we live in pragmatic conditions and circumstances,

but without the Talmud and without the word,

without language, without poetry,

people would not have survived.

- Do you think that about Americans?

Not American Jews, about America generally,

would your same hopes and aspirations

about the fostering of that tradition of 3,500 years,

would it relate to America so powerful

and so much involved in the politics of survival

vis a vis the Soviet Union,

vis a vis nuclear armament, et cetera.

- Yes, I do.

And I think of the United States,

I'm overtaken by gratitude.

That doesn't mean I'm not critical.

I am critical, but gratitude is a dominant feeling

that that I have in thinking of America.

Number one, this nation has gone to war twice

in its history to fight for other people's freedoms.

First World War, the second World War.

Then after the wars, the economic help.

The billions of dollars that we have given

to those poor countries, ravaged, destroyed by the enemy.

And even now, what would the free world do without us?

And they're always ready to help.

So I'm grateful for this country

where else really could a refugee,

such as myself, be sitting with you

and talking about history or about philosophy?

On the other hand, I'm critical.

I think for instance,

what happened here during the war

with regard to the Jewish tragedy is unforgivable.

The indifference of the United States leadership

to the suffering of the Jewish people in Europe

is unforgivable.

- [Richard] What do you think that indifference

as you call it?

And that was the word that I started the program with.

What was it due to?

A lack of knowledge or lack of information?

- Oh, no knowledge was here.

- [Richard] Then what?

- I don't know, people who were here

tell me that there was so much antisemitism then

that somehow Roosevelt had to take it into account.

He was afraid of acting too far, you know,

not to antagonize the electorate.

I'm told that even the Congress was against immigration,

that the newspapers who knew, the stories came in,

even the newspapers did not play it up

to a sufficient degree,

but all these reasons are practical reasons.

And I do not accept them.

But I know now and we knew it some 20,

30 years ago already, that Roosevelt and the military

and political leadership,

and including the Jewish leadership of this country

knew everything that was going on in Europe.

In America, they knew about Auschwitz in 1942.

I who was in Hungary didn't and in 1944,

when the Hungarian Jews came to Auschwitz,

they didn't know what it was.

Had they known, many of us would've escaped,

but Russians were 50 miles away.

Now, how can anyone explain that to me?

I don't know that.

The knowledge was here,

but somehow the knowledge did not

become an ethical knowledge.

It was one thing to know that Jews were being killed.

And another thing to know that something

had to be done for them.

And these two zones were separate.

- Today how separate are the zones for Americans?

The zones when we think of Ethiopia?

The zones when we think of other peoples who are suffering?

- I think the American nation responds.

When we saw the Ethiopian pictures on television,

there was a response.

Very powerful response in the United States.

Not enough, mind you,

because I think they should have taken American planes.

The Air Force should have given 100 airplanes

to carry the food and doctors and teachers and builders,

sociologists, or anything to go and help these people,

but still the American as an American, he or she, helped.

I know I was going around schools, high schools,

asking children to give $1.

And they gave in the thousands,

they gave dollars to the Ethiopian children.

That was true about Biafra.

That was true with the Boats people,

the American people responded.

Maybe it's a guilt feeling.

Maybe because during the second world war,

the gates were closed

that now the both people are being allowed in.

The Hungarian refugees did come in.

- You know, I'd like to come back to this question

about the nature of human nature,

unless you were to tell me it will be whatever we make it.

But given an absence of those who raise our consciousness,

given simply a feet before us,

whether it is the destruction of the Jews,

whether it is Auschwitz, Buchenwald,

whether it is what we heard during the war and before

about what was happening, without prodding,

what do you think, you and I,

and most of the rest of us

would do without the training, without the ethical training?

- What is ethical training?

It's teaching.

We are teachers.

We write and we speak and we teach.

That means we train other people.

In order for us to be able to train,

there's only one, to me,

one very important component: memory.

As long as we remember, we can train and we can sensitize.

I was teaching out at Yale for a year.

I remember I asked my first class,

what is the opposite of literature?

- [Richard] The opposite of literature?

- And they all tried to give me answers.

You know, ignorance and so forth and vulgarity.

The real answer is the opposite of literature

also is indifference

because it is the opposite of everything else.

The opposite of love is not hate, but indifference.

The opposite of culture is indifference.

Now, therefore the aim of literature to sensitize.

The aim of culture is to sensitize.

The aim of television is to sensitize.

So if we remember, we can sensitize.

If we don't, then we are no longer sensitive either.

And then.

- But you see you describe,

and I feel compelled to ask you to prophesy.

You're in the tradition of prophets,

what would be your assumptions as to where we are going

in terms of our sensitivity to suffering

in terms not of our indifference,

but of our devotion, our concern?

- Profit ceased to prophesize some 2,500 years ago.

There are no longer prophets.

Still, if I had to foresee the future,

I would be terribly pessimistic.

I'm pessimistic because of the nuclear threat.

And to me, although I never compare anything to Auschwitz,

nor do I compare Hiroshima to Auschwitz,

we should never do that.

But I think one is a consequence of the other.

Auschwitz paved the way for Hiroshima.

- [Richard] As a response?

- Not a response, as a possibility.

It's possible to kill a community of people. It's possible.

Now today there are so many nuclear weapons.

And fortunately, for the moment,

the big powers I think are responsible. They won't use them.

But one day, smaller nations will get hold of them.

And we know they will.

What then?

Just imagine a Khomeini with nuclear powers.

But he would use them right away, not against Israel,

by the way, but against Iraq.

Imagine Idi Amin 10 years ago with nuclear weapons.

And that is really my fear.

But at the same time,

I have the feeling that something is happening

in our country.

It's happening among the young people,

a certain awareness, a moral awareness.

So I'm oscillating between ultimate despair

and necessary hope.

- Perhaps an unfair question.

If you felt just precisely the opposite,

would you tell me so?

- Absolutely.

I belong now to a age generation.

I don't play big words anymore.

- So that your,

this touch of optimism or hopefulness is genuine.

- It is. Of course.

But it's also an existential leap, as you know.

- [Richard] Say more.

- I have no choice. I must.

It's because the despair is so strong.

I must fight it.

In order to fight it, I must cling to some hope.

- That attitude is that what you think produces how,

progress, let's say, that existential jump?

- What do we call progress?

If it's technological progress,

I think our generation suffers from it.

We go so far in technology that we remain behind in morality

or in philosophy, just to see the discrepancy

between what we did in science

and what we did in salt in metaphysics

or even poetry or in art.

So what is progress?

My feeling of course,

progress must be translated in human terms,

in words of wisdom, compassion,

and we did not make much progress.

- Do you think that your words at the time

turning the clock back now of Bitburg

of the president's visit,

your very, very active, shall I, perhaps not political

is not the word,

but your intense ethical involvement in these questions,

were they Wiesel-ish or do you in any way regret

having moved from your study, your teacher,

but having moved from your everyday work at writing?

- In a way, yes, because I told you before

that I lost six weeks.

For the first time in my life, I didn't study,

nor did I write for six weeks.

And now I have to catch up this six weeks.

- Which was the indulgence?

- It's too much because I realize the importance,

the historic importance of the event, that it,

we must do something, we must speak up,

because it was a watershed.

And even today, I think it was a watershed

and therefore we had to do something,

but it didn't help much,

but still a few people listened.

A few people learned.

A few people felt that now they must learn more.

I don't regret it.

- But you see, that's why I ask when I jokingly,

and I have no right to joke about it,

ask which is the indulgence,

I really meant is the avoidance,

had the avoidance of that kind of involvement,

been the indulgence, or was the activism?

- I understand it.

- [Richard] Which way will you go now?

- Oh, I go back to my study to my writing.

I am not good as an activist.

It's not my role.

- [Richard] You were very good.

- No, no, I'm not really.

I'm not good for me.

- [Richard] When you came into this study, into this studio,

I shouldn't say study,

maybe that's a slip that I should not make.

It is clear to me that so many people remembered you,

not just as the author,

and as the historian of the Holocaust, as the moralist,

as a person who took a very strong role at Bitburg.

- Well, I don't regret it,

but is really not something I like to do.

I really like better to be with my students in my classroom,

in my study and read, and read, and read, and write.

- [Richard] Where is it written

that you should be able to do what you want to do?

- It's not, I don't.

The fact is I'm sitting here with you

speaking on television. - Indeed.

That's what makes me wonder whether you have not felt

some compulsion to do something more.

To be involved more.

- No, really.

I would lie if I were to saw I felt a compulsion.

I don't take myself that seriously.

Not in disrespect.

However, again, once I did it, I felt I had to do it right.

Not to say things I would regret later.

And I feel that I did not say anything that I regret now.

I try to endow every word that I said

with a certain meaning, which is mine.

And with respect to other people's words.

- I think not only do you show that respect,

but I think the world shows you that respect.

Feels it very deeply as I do.

And I want to thank you for joining me today, Elie Wiesel.

And thanks too to you and the audience.

I hope that you'll join us again next time

here on the "Open Mind."

Meanwhile, as an old friend used to say,

goodnight and good luck.

[jaunty music]