[upbeat music]

- [Announcer] "Why In The World" is made possible

by a grant from General Motors Corporation.

[upbeat music]

- Hello, I'm Ken Alvord,

and welcome to "Why In The World."

May 7th marks the 40th anniversary

of the end of World War II

and the victory of the Allies over Nazi Germany.

And the winter marks another anniversary, too,

the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps

by Allied troops in the final months of the war.

Cold monuments of stone and ash remain

to give silent testimony

to the 6 million Jews who perished,

victims of Hitler's demonic policy

which became known as the Final Solution.

Under this policy, the Nazis set out

to systematically exterminate the entire

Jewish population of Europe.

6 million, it's a hard number to comprehend,

but in terms of individual lives,

one life taken in its unique richness,

one future destroyed, one potential unrealized,

and talents untested, we begin to understand

the terrible loss to mankind.

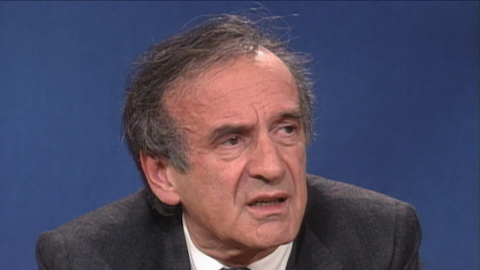

Recently on ABC's "Nightline" program,

one Holocaust survivor, Elie Wiesel,

poet and author, returned to Auschwitz,

and there, recited his poem of remembrance.

- Listen to the wind

for there is nothing else you can listen to.

For this was the place

where children became old

and where old men had no children to console,

and they all died.

[wind howls]

Listen to the stones,

for the stones themselves are broken

as our hearts were broken,

for this is the place of eternal night.

[wind howls]

In this place people were abandoned, doomed.

Mothers, children, grandparents, brothers, sisters.

Imagine, 4 million people lived and vanished overnight

in this place.

A whole nation could be built with 4 million people.

There could be enough doctors,

enough teachers, enough parents, enough children,

enough princes, enough kings, enough merchants,

enough dreamers, enough teachers, to build a people.

This is no cemetery.

Those men and women and children,

those old Jews,

those Jewish children,

those rabbis and their disciples,

the singers of songs,

the dreamers of dreams.

They perished here and they have no cemetery.

They don't even have a cemetery.

We are their cemetery.

- Now, decades later, we are still trying to understand

the full magnitude of this unconscionable crime,

and to help us understand its place in history

and the lessons we might learn from it,

both for our generation and those to follow,

we've invited a guest on the Holocaust,

Dr. David Wyman, Professor of History

at the University of Massachusetts and author of the book

"The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust."

And let me ask our student panelists this week

to introduce themselves.

- My name is Danielle Phillips,

and I'm a senior at Mamaroneck High School.

- My name is Jess Gaspar,

and I'm a junior at North Hunterdon High School.

- My name is Sara Ralph,

and I'm a junior at Hunter College High School.

- My name is Dean Silverstein

and I'm a senior at Chatham Township High School.

- Well, just to kick things off,

let's put them in perspective.

You're a Christian,

the grandson of two Methodist ministers.

What motivated you to pursue the subject of the Holocaust?

- I can't pin down an exact specific reason,

but what, I know what it does go back to

is a question that I hope we'll get into today

in a little bit of detail.

That is this,

that the Holocaust was not only a Jewish tragedy.

It was, of course, a Jewish tragedy,

but it was also a tragedy for Christians.

It was tragedy for western civilization

that it should have happened in that culture.

And of course, for all of humankind.

Particularly my concern and my distress is in regard

to the Christian role in the extermination of the Jews.

It was people of Christian background who were the killers,

the perpetrators.

Now, many of the Nazis had rejected Christianity,

but the fact is they grew up in a Christian culture,

and for the most part, were brought up in Christian homes.

And so it came out of Christian society

that that diabolical occurrence took place.

The other side of it is that those who could have acted,

those who stood by, the bystanders,

were, those who were most able to act, were Christians.

Christian nations, Britain and the United States,

and they failed.

Essentially, they stood by.

- You mentioned bystanders.

A lot of people point to Hitler and say

that he was the sole reason why the Holocaust occurred.

But insane and crazy as he was,

it seems impossible that 6 million Jews can be destroyed

and millions of other groups killed

if one person was the cause.

Who else was to blame, then?

- Well, certainly there was a whole a hierarchy

within the German, the Nazi party,

and the governmental structure that participated in it.

Whether, without a Hitler,

there would have been a Holocaust,

it's an impossible question to answer.

There's no doubt that Hitler was a key igniter

of the development.

- I want to ask you one question.

When we were talking this over before,

we kind of discovered that each one of us

had found that a lot of people in our schools,

or just in general, a lot of people didn't know

very much about the Holocaust, about Auschwitz.

I think he was saying that, you know, like,

one person in school had heard of it,

and that's not true of me, but it really horrifies me

that American kids don't know about the Holocaust.

- [David] I'm surprised.

- Exactly, and you know coming off of this is,

exactly for those people,

what led up to the Holocaust?

What led up to the extermination of 6 million Jews?

And you know, you say, Hitler,

what was in the minds of the average German?

They could just say, oh, you know, we just send off,

you know, a million more and they were killed.

- I don't think the average German did it.

There's no way we'll ever know what the average German knew.

The average German isn't telling,

and there were no polls or anything taken.

But I don't think that the average German

would have carried it out.

One would probably conclude that there was something

in German culture that permitted that to happen.

Although, again, we don't know how much people knew.

They certainly knew

that Jews were disappearing from their areas.

They were told they were going to labor camps.

- Specifically, though, what rationale,

political or ideological rationale,

was used within the Nazi party to say, okay,

that somehow,

A, this is going to be, we will be able to sell this notion,

at least if not that they are to be exterminated,

at least -

- Get rid of them.

- Each person knows that they're going to go somewhere

that's not here.

- [David] That's right. That's right.

- And B, that people will put up with this,

and that we'll get something from it,

that we'll gain something that's worth

all of this agony and pain.

- The Nazi ideology, and it's hard to know

how widespread this belief was in Germany,

but I think that it caught on

given that these were times of tremendous stress.

The '20s were bad in Germany with a terrible inflation.

The '30s came the depression, which probably was worse.

And then the emotionalism that's involved

in a full-scale war.

That is to say there was a lot, I think,

of instability in German society.

The Nazi ideology regarding Jews,

the things that Hitler and other leaders believed,

it took me five years of teaching this

before I could believe they believed it.

But I am convinced now that they really believed

that the Jews were a world threat,

that there was a conspiracy afoot

by some Jewish leadership, a mythical Jewish leadership,

in the world to take over Germany,

to assault the whole Aryan race beginning with Germany,

which was the great cream or outcome,

the high point of that kind of culture.

And they were persuaded that from the one side,

communism was a Jewish manifestation.

And we've probably run into that.

You've heard the reflections

of this kind of prejudice before,

and that Russia was run by the Jews.

Then on the other hand,

capitalism was a Jewish manifestation,

that Roosevelt and Churchill were puppets of the Jews.

There's a paranoia about it where they're coming in

to make life difficult or impossible for Germans.

If you accept that, what do you do to that?

- You might go after the leadership, right?

- Well, what I'm thinking is that theory, that ideology,

that mindset atypical to Germany?

I mean, when you look at the,

take a look at the American society at that time.

It's incredible to see the antisemitism present.

And there was a poll taken, I think,

cited in your book where a poll was taken among Americans

and a lot of, a lot believe that exact mindset

which you just said.

- Not that many. It's a fringe element to America.

- Well, there's that fringe group,

and then there's a fringe group

who was somewhere in the middle between,

wasn't disbelieving it but was saying,

well, yeah, it could happen,

and people who really believe that, not as radical,

but people who believe that Jews were bad

and Jews were money hungry

and Jews were at the root of some of the problems.

- We can even say,

this happened to the Japanese in the United States,

maybe for different reasons.

Maybe in the middle of the war, the Japanese were a threat,

but it seems to me, maybe the Jews were just that group.

Every nation maybe has that group,

that scapegoat group that can be picked on

when the time gets right, you know.

And we picked on the Japanese when the time got right.

You know, we tried, I seem to remember, you know,

the Chinese, Japanese Exclusion Acts, you know,

it's not like it was all of a sudden

because of the war threat.

- It was an outsider group.

- Maybe it's just something that -

- Bigotry, or the attempt to pick on somebody.

It is a common machine.

It is a terrible machine,

but it is not a machine run wild like this.

It is not a machine that says I will track down

the children and the children's children

and I will exterminate basically a race, if I can,

a people.

Isn't there a difference in quality to that?

This is unique.

This is unusual.

- That view of Jews as a threat, as a world threat,

even sometimes extended to the idea that Jews were,

had criminality in their genetic structure.

So the misconception, of course that Jews were erased.

But this went around, and even to the extent

that the Germans were, this was in the educational system

in the '30s.

The Jews were a lower form of life,

that they were parasitic, that they carried diseases,

that, just a terrible image of Jews.

That seems to have gotten loose in Germany

and pumped through German society

through the educational system in that period.

It didn't happen in other countries except

in Eastern Europe, antisemitism was as bad.

There is a riddle, in a sense, why didn't the Holocaust

happen in Poland or in western Russia?

This is where Hitler and the Nazis come in.

That's what's different.

- Yeah, the Americans knew what was happening

to the Jews, though.

No matter what they believed they were like,

if they believe they were a lower life form,

they're still human.

What did they do to -

- I don't think that that perception,

that very negative perception of Jews,

had currency to much extent in the US,

but there was a negative tendency.

And you mentioned in the polls that Jews are aggressive,

they're money grabbers.

That's kind of, overly aggressive.

That was widespread in American society.

What I believe that did was it tended to

inoculate Americans or to hold Americans off from helping.

- Not only the Americans, but in Congress itself,

there's this, there's a very big anti-Jewish tide.

- It could even be worse.

One could even argue it was worse in Congress

than in the population as a whole.

- [Dean] Right.

- There were some very bigoted members

of Congress at that time.

- What could we have done, though?

I sometimes wonder what the answer to that is.

You know, it seems like we should have done something,

but what could we have done?

- Let me go back and reroute it this way.

What did Roosevelt do?

- [Dean] Nothing, really.

- Why didn't he?

- Initially, no, people don't want him to.

If the American public was not behind him,

then he's not going to do an action.

- Oh, I know, because the Jews supported him,

and by helping the Jews, he wouldn't be gaining

that many more votes, and it was political and, like -

- You're bringing it plus, putting it minus and plus.

He has nothing to gain by helping Jews

because the Jews are already supportive

and not enough other people care.

And because he might lose something doing it.

What might he have lost if he had announced,

this country is going to take action on this issue?

- [Jess] Well, he might have lost some of the votes.

- Of whom?

- Of his constituents.

You know, the people who would vote for him.

He wanted to be,

he wanted to keep being president, of course.

- What would the reaction when Congress,

given some of the things we've said?

- Exactly, very negative reaction to that.

And he would have lost,

if a President loses congressional support,

then his policies become ineffective.

- Isn't it true that the people

who would not have supported him on that basis

wouldn't have voted for him in the first place,

because wasn't Roosevelt the New Deal, lefty type?

- You're not talking about votes.

You're talking about votes for his bills, aren't you?

Or votes for the progress of the war?

- Well, votes for himself in reelection,

for his party in elections,

and support for his programs, generally.

What do you think might've happened

if he'd gone before the public and said,

this is a terrible problem, we're going to deal with it.

What negative reaction?

Where would it have come from and what would it have been?

- I think a lot of people may have felt, well,

it's going on in Germany, and it's not in our country.

And we can't invade into another country.

- Well, even when the war was on.

- [Jess] Well -

- We were at, this was our enemy.

And one of our enemy's objectives was to kill off a people.

- We were having problems in the war ourselves.

And so I think the American people would have become

even more antisemitic if they had known that money

was going into helping the Jews

when it could have been used to help them.

- What charge might've been leveled

at the Roosevelt administration?

- They were pro Semitism.

- [Danielle] Pro Jews?

- Or even that they were fighting a war for the Jews,

which was what the Nazis said all along.

- And that's the problem with Vietnam, then.

And the same thing would've happened,

are you saying,

that people got all against the administration?

- I'm not sure what -

- In other words, in Vietnam, you're right.

Vietnam, the war was, it became unpopular.

What we were doing became unpopular.

World War II, one might argue, was successful

partially because it was a cause.

- It was very heavily supported

throughout the population.

- Are you suggesting that maybe in some sense,

that that might've disrupted that delicate balance,

and the war would no longer have had the support

that it came to have after Pearl Harbor?

- I don't think that would have been a problem,

because I think the country was very heavily supportive

of that war.

I think what Roosevelt feared was

that there might be some elements on the fringe

who began to raise hell about this and say,

this is a Jewish war, and that could have stirred up

the tendencies toward antisemitism among other people.

- But that's really scary because that can,

it seems to me like that can happen to any group.

And if you're afraid, I mean, what is it

about the human psyche that allows a fear

of action by somebody else to get in the way

of what is really, you know, what's humanity,

what is moral?

- What is there in the political psyche?

And that's the whole thing in politics

is that fear about alienating people.

And as you've said that the,

in terms of building Jewish support,

there was no need for it,

but let me now recast it the other way.

What might Roosevelt have done to have countered

that kind of potential negativism and built a constituency

in the country for a really effective rescue program?

- I would say, it seems to me that, like in Britain,

they had this whole ideological thing, you know,

that it was the Nazis were morally wrong.

Their whole system of thought was wrong.

And it seems to me

that Roosevelt could perhaps have used that,

that it could have been a very powerful thing

because they did use that in the propaganda posters.

I've seen one from World War II that has a picture

of somebody with a bag over their head

and a telegram coming in from some report or something

saying, you know, that the Germans

just exterminated a whole village in Poland or something.

- Not only England. That was widely felt here, too.

- Couldn't they have used,

couldn't that have been, maybe on the one hand,

it would have lost votes, but couldn't,

on the other hand, have been used to gain, you know,

the moral right of that war?

- And tie this in with the war effort.

- [Sara] Yeah.

- As a, and in fact, when the War Refugee Board

finally was established,

when Roosevelt was politically cornered

and had to set that up in January '44,

and the statement that came out about that,

it then became an American war objective

without deterring the war.

Nothing was to be done for rescue

that would set back the war.

But than that, it became a war objective.

So, I think you're getting at the answer there,

that he has, had he been willing to go to the public

and said, explained how terrible this was,

and what was happening and made an appeal

on humanitarian and ideological terms,

couldn't he have built a constituency?

- [Dean] Sure.

- Among that element of society that wasn't antisemitic

to counter the other.

- Right, well, it's very clear how ineffective

our government was,

but what about other governments?

There's England.

What about the Pope?

And there's another segment of the quote unquote

civilized world that was powerless,

that didn't do anything.

- The charge against the Pope will always stand.

He did not speak out in this circumstance.

The rationalization given was that

the Vatican mustn't take a position

with either side of the war.

So the Vatican condemned all atrocities

without pointing the finger anywhere.

That was an evasion. It's obvious.

Almost, someday I'm going to write a little article

about bad breaks in the Holocaust, just plain bad luck.

And one of them is that the preceding Pope,

Pius the 11th, would have been much more effective.

He said, it's a great statement.

He said that, "Spiritually, we are all Semites."

That is, he was recognizing the Christian relationship

to the Jewish religion and putting them together.

With that kind of a person,

something better might've been done.

Having said that, the Vatican did do some things

quietly behind the scenes, but it doesn't, in any way,

in my opinion, make up for the failure to speak.

- You mentioned England, as well,

or other nations in the war.

Is there anything that they practically could have done?

- What did England do that is the most to be criticized?

- [Sara] Nothing.

- Where they do it?

Well, let me put it another way.

What would have been the most logical sanctuary

for European Jews?

- [Jess] They may have said something about

there being a place in north Africa

where they could bring them with the other camps.

- Okay, that, but think of a place that's equally close,

but that there would be good reasons for Jews to go there.

- [Dean] Israel?

- Well, what was Palestine then.

Why Palestine?

Why would that have been an ideal?

- Well, it was controlled by England.

- [David] But why would it be an ideal place

for Jewish refugees?

- [Danielle] It was the Holy Land.

- It had been promised to the Jews as a homeland.

It was near.

The mass of the Jews were in south or in Eastern Europe.

It was graphically near.

And who was there, besides the British?

- [Dean] Jews, the Jews.

- There was a sizable Jewish community of half a million.

What do you think their attitude was toward taking Jews in?

- [Jess] They would be glad to.

- They would have done anything in terms of sacrifice

to accommodate, to have accommodated Jews.

So there was a ideal possibility.

Now that isn't to say that millions could have fit there,

but certainly hundreds of thousands.

- [Sara] What about -

- We're going to finish your question.

Why didn't Jews go in large numbers to Palestine?

- [Jess] They had no way of getting there.

- [David] That's a minor problem.

That could have been solved.

- [Ken] Well, in fact, some of them tried, didn't they?

- The boats, some of them.

- Remember Exodus?

- Who kept them out?

- The British?

- The British controlled Palestine at that point,

and the British kept -

- But why is it?

Why didn't they allow the immigrants to come in?

- [Sara] We didn't realize, I guess.

- Can you make a guess?

It's a hot item today, too.

- Well, it couldn't just be pure antisemitism.

I mean, there must've been -

- [David] There was more to it than antisemitism.

- Then what was the real reason behind that?

- [Sara] The Arabs.

- Who else was there?

The Arabs.

- They already had, what, race riots in '21.

- There had been riots against Jews

because in the '20s and '30s,

there had been increasing Jewish settlement in Palestine.

- [Jess] And they wanted Arab support.

- And the British wanted Arab support,

or at least they didn't want the Arabs

to raise the dickens in there.

So to keep the Arabs placated,

they said almost no more Jews.

- [Dean] What about another segment?

- So, you ask about England.

And England's response was essentially one

of keeping the Jews out of

what would have been the most available

and the most workable, feasible sanctuary.

The British record is very poor.

- What about another segment of our political system?

What about the media?

I mean, where, you hear very little from them

and where were they then?

Where were the media?

- Well, the, I guess you read some of the book.

You read the chapter at the end

where I kind of tried to summarize.

They did not give this topic, this tragedy,

anything like the coverage that news should have had.

It was considered not to be first rate news.

- But we talked a bit about England

not letting a Jewish population in.

What about the United States and immigration?

We didn't do much better than they did.

- But wasn't it, our antisemitism, you know,

rising nativism or whatever you want to call,

that we had the same problem.

- Well, didn't we have a system, really,

basically that was set up to be more exclusionary, anyway,

and we just failed to amend it.

- In the 1920s,

we had put on the records for the first time,

a numerical limitation on immigration.

And that was the setting up of the quotas,

which are given out to various countries

were assigned so many per year.

The total of that was 150,000 a year could come here,

but more than half was assigned to Britain and Ireland,

where nobody had to leave from.

That meant it was about 60,000 that were workable.

- This is our own particular hatreds, you know,

that in the 1900s to the 1920s,

it's like the European, Eastern European, Germans,

and Eastern Europeans and Russians,

they were the ones who were coming in,

and we'd had enough of them, so we said no more.

- Let's back out in these closing minutes now,

and take a look at, pull the telescope way back

and look at the legacy of this thing

and what we're left with

and what we learned from this and what we feel about this

and how this never happens again, I guess.

- Isn't there a problem already though in, like,

South Africa, I mean, in Africa,

and in the, and in South America, like, with El Salvador.

Isn't that occurring there,

but to a different type of -

- [Dean] I think -

- [David] People have been marked for extermination?

- Yeah.

- Cambodia, but I don't -

- No, well, your point is really very prevalent

because Elie Wiesel, who was on earlier,

had said in one of his statements,

"If we do not remember the past,

then we're doomed to repeat it."

But right now I mean, is it, have these people died in vain?

Have 6 million Jews and countless others died in vain

because right now, as you said, in El Salvador, they're,

if you're not familiar with it, the refugees in El Salvador,

the El Salvadorian government,

there are opposed by a counter revolution,

by a revolutionary group.

And the way they identify themselves

is by national ID cards.

And as a method of solidarity, they burn their ID cards.

So the people who are, come out of El Salvador

to get away from the war down there,

come to the United States.

And right now, synagogues and temples are harboring them.

But the United States government is sending them back,

and they're sending them back, and they,

their ideas are invalid and they're being killed.

- Well, you can, wait, you can play the same game

with the Haitian, the both people

and various other refugees coming into this -

- Like, an Afghani refugee right now

is in prison in Brooklyn.

You know, cause they don't want them.

- [Danielle] But I think -

- Okay, so does that mean, because we are wrapping up,

does that mean we're not learning?

Or what are you, what's your feeling?

You look at that, you're close to it.

You feel it.

And you look and see

what we're willing to tolerate and do or not do now.

Have we learned?

- We, the country is much more open to refugees,

political refugees.

You're talking about war refugees,

people trying to flee war.

The, it's unlikely that we're going to open the borders

to that kind of flight.

Perhaps we should, but we -

- [Dean] Isn't that what the Holocaust survivors were?

- Survivors were not fleeing the war.

- Not survivors, I mean, the people

who were fleeing the Holocaust.

- They were fleeing an attempt systematically

to take that people and rip it out, eliminate all of them.

- [Jess] Isn't the El Salvadorian government

trying to do that to the rebels?

- To eliminate, well, that's what you do with a war.

You fight one army against another.

You try to eliminate it.

I'm talking about deciding that a whole people,

because they are of that people, are to be eliminated.

We don't have that many examples historically.

- Well, there are a couple of suggestions,

and I don't want to say factually

that we know them to be true.

In fact, there's controversy over them,

but technically, take Ethiopia right now.

There've been suggestions that some of the starvation,

and of course starvation can beat Zyklon B any day.

It's cheaper.

- It was used as part of the Nazi [indistinct].

- It's going on in Ethiopia.

And that in fact, it is politically

to the benefit of some in the situation

to allow others to starve.

And that number is getting pretty high, too.

- Let me broaden it without getting into

that very difficult issue of what is extermination

and what isn't.

The media is fail, are failing again today

on issues like that.

One of the services, one of the requirements of mass media,

I would say, would be to alert people to a situation

that needs to be dealt with.

Now, we did get some publicity on Ethiopia.

It came in a rush last fall, and now we don't hear about it.

- It also came very late, according to a discussion we had

earlier this year at "Why In the World.".

- It came late, and then it stopped early.

We got almost nothing about Cambodia.

There was very little information on that.

About the Holocaust, as we've mentioned already,

almost nothing came into the press.

And that is a sort of a continuing failure.

- What I think is glaring on the media,

I mean, if it's true that, you know,

that the friends of all of us

have never heard of the, Auschwitz,

have never heard of the Holocaust,

how could people learn

from something they've never heard of?

Maybe the failure is also in our education,

that we don't know, not just not, I mean,

obviously we don't know enough about current events.

I admit it personally,

that I don't know enough about current events.

And perhaps you can't know

when these things are gonna happen unless you know

the background to them, you know.

- Not just our schools, but in our government also,

there is the failure to pass the genocide bill,

and there's also a failure to pass a bill

that would allow the refugees three-year asylum,

the El Salvadorian refugees three year asylum,

the DeConcini Moakley bill.

It's a failure to realize our past.

- Let me break briefly to say that

we're obviously going to continue where we are.

Hope you will, too.

And we hope you'll join us for the next "Why In the World."

[dramatic music]

- [Announcer] "Why In the World" is made possible

by a grant from General Motors Corporation.

[inspirational music]