[bright music]

- [Narrator] The following program is from NET,

the National Educational Television Network.

- The people now called Negroes are the most written about

and the least understood of the world's people.

- This term, Negro demoralizes us and is detrimental.

I feel it doesn't give us,

give us any association past the slave ship.

- I think that the first tasks of people of African descent,

whether in the United States or in Africa or elsewhere,

is to get rid of this slave name, Negro.

- This curious word Negro was seldom

or never used in Africa itself

and this word has no meaning

or no worthwhile meaning at all in Africa.

I would doubt myself

if it has any useful meaning anywhere else.

- What is a Negro? A simple question.

But the answer's not so simple.

[gentle music]

My name is Ossie Davis.

I'm an actor and a writer and the narrator of our series

of programs on the history of the Negro people.

I am also a Negro.

What is a Negro? In Africa the word Negro has no meaning.

In Brazil, the Negro is a man

who is very poor and very black.

And in the United States,

a man who has any quantity of Negro blood

or whatever that is, is considered a Negro.

Are Negroes a race, a people or a condition?

Our programs are will be asking this question

in many ways and in many different settings.

Our odyssey will take us throughout the world,

to Africa where we will explore the relationship

of American Negroes to the land of their origin.

To Brazil where we will ask, "Is Brazil a racial paradise?"

and throughout the United States.

Our aim in this series is both a modest

and an ambitious one.

We will be asking many questions

and perhaps answer only a few.

For there is a vast ignorance of Negro history

among whites and Negroes,

and the job of filling this vacuum is massive.

Do Negroes have a heritage and a tradition

like the Greeks, the French, the Anglo-Saxons?

Or are we something less, as others have portrayed us?

Everywhere we have looked,

we have seen Negroes as savage and barbaric,

humble and self-sacrificing,

scared and childish and inferior.

And I remember as a kid coming from some of the pictures,

and we spent the whole time from the motion picture house

to home satirizing the Negro performances

we saw in the film.

Well it was also an admission

that somehow or other this was to some degree what we were.

Now these important and very, very impressionistic things

that we got from these films did

to some degree govern our behavior.

When a Negro child goes into a movie, for instance,

and sees himself or sees another Negro

in an unfavorable light,

he feels to some degree threatened.

He feels uncomfortable and a great deal of his laughing

at that situation will be the kind of laughter

that protects him.

It's a nervous attack against him, his self,

the way he looks at himself,

the esteem with which he holds himself

and how he will rate with his fellows in the streets.

You know, it's seeing something happened to you

that you can't control, which leaves a scar,

which leaves you feeling inadequate.

You know, you don't feel loved,

you're ashamed to look at yourself, ashamed to go home,

ashamed to talk to the boys next door,

ashamed even to ask these questions of your parents,

although sometimes you do.

It's a horrible situation

and sometimes you never get over that.

- [Man] As a Negro, I have honestly tried to believe

that I was somebody and I've always fought

during my life to keep that feeling

that I did have some value.

And I say value knowing what that word means.

And it's been many a nights in my life

when I went to sleep and known very deep inside me

that I really wasn't worth much.

- [Woman] I still do not really know

what being a Negro is or what it means.

It means that my skin is a little bit darker,

it means that my cultural exposures have been

somewhat different to other ethnic groups.

It may even mean that as a human being

I might be more sensitive to need and despair.

- [Man] Oh yes, ah, you know,

I wish I was white kind of thing,

when you begin to sort of get the feeling, of difference,

like maybe you're dirty or something's wrong,

but there was that feeling, you know,

so early that you can't even remember where it started.

I know, but yet, it's part of my American heritage.

- [Ossie] We were told we were a people

without a past and without a future.

And Negro boys and girls learned before very long

that they were something special.

- [Woman] You know at an early age,

soon as you start school,

you begin to catch on to the whole racial thing.

But once you get into school you begin to know it

and know there's a difference

and that the difference is against you.

- [Man] There's no real reference to me as Negro,

or to my father or any of the other Negroes

who have contributed so much

to the growth of the United States.

And I really can't understand it.

- [Woman] I'll never forget the picture

in the geography book,

a couple of very ragged Africans, you know.

Weeks before we got to the lesson,

we were stealing ourselves for it,

some Negro child would find the picture first in the book

before we got to the lesson and alert everyone,

look on page 22.

You'd see what's there

and then we dreaded reaching that lesson

because it was always something

about the savages not knowing anything yet.

We had to sit there and hear this

and instinctively the white children would turn

and look at the Negro children, you know,

while this lesson was going on.

- And so Africa became our shame and our torment.

We were told that our past was barbarism

and the white man, our redeemer.

Slavery was not a sin, but salvation.

If few of us had anything to look forward to,

we were afraid to look back.

In 1958, Lorraine Hansberry wrote a play,

"A Raisin in the Sun," that showed the conflicts created

for American Negroes by their African past.

[upbeat music]

- Well, what have we got on tonight?

- You are now looking

at what a well-dressed Nigerian woman would wear.

Isn't it beautiful?

- Hey, look honey, we're going to the theatre.

We're not going to be in it, you know.

- [Beneatha] George, I don't like that.

- Do you expect this boy

to go out with you looking like that?

- [Beneatha] Well, now that's up to George.

If he's ashamed of his heritage.

- Oh dear, oh dear.

Here we go again, a lecture on our African past,

on our great West African heritage.

In one second, you know, we're going to hear all

about the great Ashanti empires,

the Songhay civilizations, the, the sculpture of Benin,

some poems in the Bantu,

and then the whole monologue is going to end up

with the word heritage.

Let's face it baby, your heritage ain't nothing

but a bunch of raggedy spirituals and some grass huts.

- Grass huts!

Oh, you see, George, you see, you would rather stand there

in your splendid ignorance and know absolutely nothing

about the people who were the first to smelt iron

on the face of this earth,

while the Ashanti were performing surgical operations

when the English were still tattooing themselves

with blue dragons.

- [Ossie] At the heritage program of, "How You Act,"

a federally sponsored effort to develop better opportunities

for Harlem's Negro youth,

a new version of African history is being taught.

Robert Moore is a visiting lecturer.

- Mr. Moore, do you think the so-called Negro

will dignify his identity by associating himself

with his ancestral background from Africa?

- After some three or 400 years

of trans-plantation from Africa into America,

it is obvious that we are not Africans anymore.

We are Afro-Americans, Americans of African ancestry

and that connects us, basically,

with our original heritage and culture.

- The accomplishments of Africa before and after-

- [Ossie] The director of the program is John Henrik Clark.

- this accomplishment is generally glossed over

or neglected in human history.

A lot of this, the misconception of Africa

and the distortion of African history is involved

in a word that is relatively new.

The word Negro, a kind of nick-name

that grew out of European laziness,

the inability or the lack of a desire

to give Africans their proper identity.

In the period when the Europeans had

to justify the exploitation of Africa

and the demeaning of a whole people,

they systematically started the effort

to weed the African out of human history.

- A great deal of our ignorance of African history sits

upon the old conservative, racial discrimination

and prejudice, which we have had in the-

- [Ossie] Basil Davidson is a British writer

and historian on Africans-

- United States, it's still sits upon the belief

perfectly unscientific, quite un-based

in any scholarly discipline that the Africans,

that is to say, if you like, the Negroes,

are people of some sort of inferiority to others

and therefore have not been able to develop in the same way.

Now, you know, the great myth of the colonial era,

the great myth took the shape of saying that the Africans,

the Negroes are our children and because they are children,

its said failing to develop, we the Europeans,

you the Americans must go in there

and show them the way they should go.

Civilize them, introduce them

to the blessings of orderly life.

One of the misunderstandings you see,

about Africa is the apparently primitive material nature

of their civilization.

You look at these people living in these villages

and you wonder what is there past?

Do they have a past? What lies behind the door.

They have nothing but a few straw buildings,

nothing but a few cattle.

It seems quite inconsiderable to think, for example,

they have no stone in their country.

They have almost no metal,

half their country is under water half the year.

They cannot build, and could never possibly build

an imposing material civilization,

but their achievement was of course

to learn how to master their environment.

And this they have done with quite outstanding success.

So that the outside picture of, the superficial picture is,

gives no indication at all of the depth of their country.

These are the people who have mastered the problems

of taming this difficult, vast continent

with all its extraordinarily great obstacles to living,

its swamps, its desert, its mountains and its prairies.

The story of Africa over the last 2,000 years

has been one of quite epic dimensions.

[melancholy music]

- [Ossie] Africa, endless deserts,

scorching and wind swept by day, bitterly cold at night.

And the Sahara, the world's largest desert,

the harsh bleak expanse

of land challenging anyone to cross it.

Snow capped mountains near the equator, gigantic waterfalls

and the jungle mists and rain almost daily.

These were some of the barriers to penetration.

To the outside world, it was the Dark Continent,

a land of mystery where stories were spread

of giants and dwarfs, of people's whose heads grew

under their arms, of monstrous animals.

[dramatic music]

It is here in this forbidding other world

that what may be the remains

of the first man were discovered.

In 1959 in Tanganyika,

a scientific expedition had been digging for weeks

in the sun baked earth looking for traces

of the earliest man.

Then in July, Dr. Lewis Leakey and his team found

what he called Zinjanthropus,

nicknamed The Nutcracker Man

because of the strength of his jaws.

He was about 600,000 years old and maybe the creature

that makes Africa the real cradle of mankind.

[pensive music]

The records of ancient Africa began

with Egypt about 3000 B.C.

Its spectacular achievements of the monumental pyramid

and brooding Sphinx, have always been credited

to Asia and the Mediterranean.

But there is growing evidence

that Egypt holds more than originally thought

to the land to the south, Cush, the land of the Negroes.

About 700 B.C., Cushite kings conquer Egypt

and become the 25th dynasty.

Little is known today about the land of Cush,

but in the ancient world it was highly respected.

In 1791 the French philosopher,

Comte de Volney wrote of the Cushites,

a people now forgotten,

discovered while others were yet barbarians,

the elements of arts and and the sciences.

Then in about 325 A.D.,

Cush is attacked and destroyed and disappears from our view.

For the rest of Africa,

there is little we can say for certain.

Except for the Cushites, Africans had no writing.

They kept in their memories, the history of their people,

stories narrated down from generation to generation.

This oral tradition must tell us much of the history

that will fill the gaps in our knowledge.

In the western Sudan, Negro kingdoms arise

in the medieval periods

of walled and fortified cities, markets and fairs.

Ghana is the earliest of these civilizations,

going back to 300 A.D.

In the 8th century, an Arab writer tells us

that the Arabs sent an expedition

to this pagan land of gold.

African markets, the main source of gold

before the discovery of America.

Then about 1067, Arabs from the north,

fired by their new faith, storm into the western Sudan.

[dramatic music]

[dramatic music]

After years of fighting,

the Arabs conquer Ghana and settle there.

From this time on, trans-Saharan caravans trade flourishes

and with the trade comes Islam.

Islam spreads through West Africa.

When Europe was going through a so-called Dark Ages,

Muslim culture is the main advancement of human knowledge.

Most important of all,

a written language comes to the west in Sudan.

Almost all that we know about these kingdoms was preserved

for us by Arab and Negro scholars of that time.

Around the 12th century,

Ghana gives way to the empire of Mali.

In 1324, King Monsa Musa makes a pilgrimage

to Mecca with a caravan of 60,000 people.

An Arab traveler arriving in Mali in 1353 wrote,

"The Negroes have a greater abhorrence

of injustice than any other people.

Neither traveler no inhabitant of this land has anything

to fear from robbers or men of violence."

Could the same be said

of the 14th century England or France?

The kingdom of Songhai, most famous for its university,

the fabled Timbuktu.

Students and scholars

from all over the world came here to study.

A Moorish traveler wrote,

"More profit is made from the book trade

than from all other branches of commerce."

- If we ask ourselves a little more nearly,

what have been the cultural contributions of African people

to the rest of the world,

then of course we are faced immediately

with the remarkably original and outstanding quality

of their plastic arts.

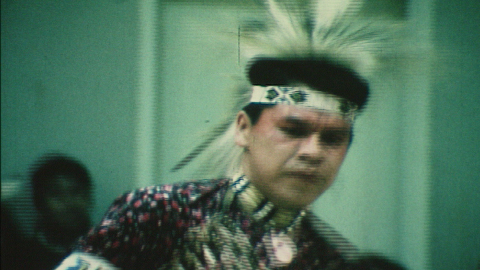

The most important art in Africa has of course been dancing.

And dancing has passed into the folklore

of the whole of the rest of the world

from its African origin.

So if you're go to places like Brazil or the West Indies

or the southern United States,

you will find African dances still being danced there.

Though, of course, in different circumstances

and therefore in somewhat different ways,

but the whole concept of rhythm as being an expression

of the personality and not simply a wiggling of the body,

and a wiggling of the body is all

that most Europeans can achieve.

But an expression of the personality

this comes from the African concept of dancing.

More obvious is the tradition of plastic art.

A large number of African peoples have developed forms

of sculpture in wood or in stone,

or in ivory or in brass or bronze,

or iron or gold which are of great effectiveness

and great originality, and this too, of course,

is passed into the general Western tradition

of pictorial art and to some extent of plastic art as well.

- The remarkable art of Benin and Iffe.

The bronzers of Benin was said to be worthy of Chiliene.

Europe was was amazed at the discovery

that Africans could perform

such an impressive creation of bronze casting.

African sculpture burst upon the European art world.

It became a major influence in the modern movement.

Picasso, Braque, Modigliani, Lejer, Degas found

in African sculpture a freedom and a vitality

they had been searching for.

Here was no slavish imitation of nature,

something the camera could do better,

but a new and fresh way of looking

at the world behind the appearance.

We have only skimmed the surface of the history

of African civilizations

and there are wide gaps in our knowledge.

Among the riddles of ancient Africa are,

where did the Negro come from?

What happened to the Cushites after their defeat?

Where did the sculptors of Benin learn

their remarkable skills?

We haven't even begun to penetrate some of these mysteries.

Yet growing knowledge and interest

in Africa is rediscovering a world

we never knew and many Negroes are examining

for the first time the values that were lost.

- My name Yule Missy

and I am addressing my question to Mr. Clark.

I want to know what happened

to the so-called Negro culture in America?

- The most tragic destruction

of African culture was the destruction

of the African culture brought to these shores,

brought to American shores.

Now the first thing they did was to forbid the drum,

forbid all African ceremonies, forbid African ornaments,

literally to destroy a people in such a manner

that they had to be remade in an American image.

This was not exactly true in the West Indies.

It was slavery, make no mistake about it,

but because it was on an island,

many of the Africans could communicate with each other

and maintain some of the African culture.

While in the United States, it was impossible

because as they arrived,

mother, brother, sister were split up

and they went in opposite directions.

Then they were resold.

They might have been resold,

within a matter of days after they were sold the last time.

So it was difficult for relatives

to keep track of each other

and it was difficult for a continuity

to be maintained in African culture.

This was the beginning of the fragmenting

of our family in this country.

It was also the beginning of the demeaning

and the negation of the masculinity

of the black male in America.

This demeaning of our culture,

this weeding us out of the commentary

of human history has left deep psychological scars.

What we are trying to do now is a massive job

of rebuilding the inside,

the spirit, the hopes,

the history, the culture of a people.

We're trying to restore those values

that have been taken away

and we're trying to get across to black youth

that they have a part to play in the making of a new world.

They have the imagination.

They have the energy.

You must first restore that part of yourself

that has been negated by oppression.

It is as essential to you as bread and water.

It is part of a food that must feed your spirit

in the world of tomorrow.

And it is part of what you will have to transfer

to your children.

[pensive music]

[pensive music]

[bright music]

- [Narrator] This is NET,

the National Educational Television Network.