TRANSCRIPT

[gentle trumpet music] [upbeat music] - [Narrator] From the dawn of civilization to the 21st century, there's been one creature we've relied on more than any other.

The cow.

It's a relationship that has shaped our lives in so many ways.

We worship them.

[priest chanting in foreign language] - [Narrator] Study them.

- The key to the cow's success lies here, the rumen.

- [Narrator] Use them.

- You never really know quite how your day's gonna turn out.

- [Narrator] Show them.

- [Farmer] They've got great udders on them, is what he's gonna be looking for.

- [Narrator] Sometimes they can be utterly frustrating.

[cows mooing] - [Farmer] This is ridiculous.

- [Narrator] Whether in fact or fiction.

- The story of "Jack and the Beanstalk," when Jack sells the family cow for magic beans, the mother is appalled.

- [Narrator] We simply could not do without the cow.

[dramatic music] - [Announcer] This program was made possible by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

[soft, bright music] [cows mooing] - [Narrator] This is the animal we see grazing in a field as we drive along the highway.

They have a timeless quality, as if they have always been with us, and we have always known them.

In short, we take the cow for granted.

John Webster, professor of animal husbandry, veterinarian, and author, has no doubts about the importance of the cow in inhuman history.

- The cow really is perhaps the most useful animal there is.

We think of food in the form of meat and milk and cheeses and everything produced from milk.

In addition to that, the cow, of course, gives us clothing and shoes from her leather, and over the course of history has been expected to work, to plow the land to grow the arable crops, and of course, her dung makes excellent fuel and excellent fertilizer.

You've got fuel, you've got fertilizer, you've got clothes, you've got food.

What more could you ask?

[cow mooing] [cow mooing] - [Narrator] A new member joins the extended family of 1 1/2 billion cattle on the planet.

Even before it's born, it is welcomed to the highly-social herd.

[cow mooing] Despite big, wide-set eyes, and excellent all-around vision, cattle see only 1/16 as much detail as humans.

[cow mooing] But they have an excellent sense of smell.

In the wild, the calf will hide from predators.

Its scent ensures its mother can find it.

The bond is formed in the first few vital minutes of life as the mother licks her calf dry, stimulating its circulation, and helping it to its feet.

[flies buzzing] [cow mooing] But this is no wild animal.

It is a Holstein Friesian, a domestic dairy breed representing centuries of careful human selection.

[flies buzzing] [cow mooing] [soft, bright music] How did this extraordinary partnership come into being, and why did the lives and fortunes of cows and humans all over the world become so intertwined?

The story begins 30,000 years ago.

[mysterious music] Deep within the Earth, the first artists recorded the beginnings of the most important relationship between man and animal the planet has ever witnessed.

Some archeologists think cave paintings like these were created by shaman as magical invocations for a successful hunt.

One of the most common images is that of Bos primigenius, the now-extinct auroch, the ancestor of the modern cow.

[suspenseful music] Weighing 2,000 pounds, with deadly horns, the auroch was a formidable beast.

[suspenseful music continues] [fire crackling] But a single animal could provide the clan with more meat than they could eat, as well as bones, sinew, and guts for making weapons.

It gave horn and hooves for tools, and hide for clothes and shelter.

The auroch was the Stone Age supermarket, giving our ancestors everything they needed for survival.

30,000 years later, cooking on an open fire still touches a primal nerve, and binds the tribe.

[upbeat music] - If we share meal with our neighbors, to me, there's a big difference, and part of it's just that meat's cooked outside and this kind of atmosphere.

- You know what I like.

- Medium-ish would be great.

- Thank you very much.

- [Narrator] A barbecue taps into our hunter-gatherer past.

- My appetite's fairly strong those days.

Thank you.

- [Narrator] But eating beef no longer requires a life and death battle with a formidable adversary.

8,000 years ago, something extraordinary happened to change all that.

[soft, bright music] - Hey!

Hey!

- [Narrator] The first cows came out of the forests and savannas and into the fields.

Whether they came of their own accord or were caught is still debated.

But the combination of bovine brawn and human brains would change the destiny of both species.

- [Cowherd] Hey!

Hey!

- Domestication was our first step in taking control of nature.

In harnessing the power of once-wild animals, we would utterly transform life on Earth.

- [Cowherd] Hey!

- [Narrator] Laurie Winn Carlson is the author of "Cattle: An Informal Social History."

- It appears that domestication of cattle began about 8,000 years ago in three separate locations.

One location is Mesopotamia, and another was in Indus River Valley, and the third location now is believed to be Africa.

- [Narrator] From these centers, domestication spread across Eurasia and throughout Africa.

[cowbells clanging] All over the planet, there were hundreds of potential choices for domestication.

[brooding music] But it was was the cow that became early man's most important ally as the hunter gatherer-lifestyle gradually settled into agriculture.

[people shouting] What made the cow so special?

[people shouting] On the plains of East Africa, where earliest man first hunted, we can still see what our ancestors were up against.

The criteria for domestication is uncompromising.

Very few species would pass muster.

If an animal is too flighty, or depends on mass migration for survival, it fails.

If it cannot breed in captivity, it fails.

If it grows too slowly or too large, it fails.

If its diet or the conditions it needs are too specialized to recreate, it fails.

If it is too aggressive, it fails.

The cow passed all these exacting tests to become the most important member of a very exclusive club, the domesticates.

Our ancestors chose wisely, and there have been very few additions to their original list of animal allies.

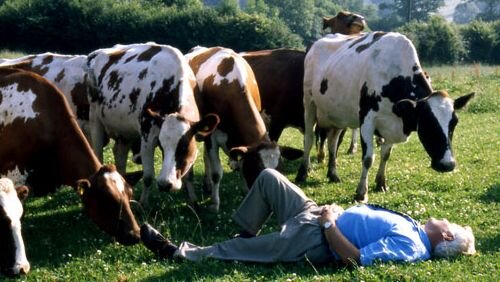

- It seems that cattle's herd behavior is what made them so suitable for domestication, because they like to stay in a group, they seek solace in the group, and they stay together.

And by them following their self-selected leader for where they choose to go, it's been easy for man to take that place and to become imprinted as the leader of the herd.

And on the other hand, animals that are quite nervous and have a nervous temperament and exhibit flight response, when man appears, they just jump and run, and there's no chance for interaction.

So it was that pause that cattle have, that curiosity, the security that they have within a herd, they feel very secure when they're all together, so they don't up and run and run off.

And so it gives that chance for man and cattle to bond.

[dramatic music] - [Narrator] In every new relationship, there are new responsibilities.

But who exactly was in charge, man or cow?

Although the cow pulled the plow, man too was set to work.

- [Cowherd] Hey!

Hey!

Hey!

Hey!

- [Announcer] This is BBC Radio Devon.

- [Newsreader] It's six o'clock on Wednesday.

Good morning, Devon.

- [Narrator] The day for English dairy farmer, Mark Evans, begins at first light.

[upbeat music] [rooster crowing] The routines on Mark's 400-acre organic farm in Devon are dictated entirely by his 250 pedigree Ayrshires.

He milks the herd at 6:30 each morning.

It's a routine that is uninterrupted seven days a week, 365 days a year.

- My father always used to say that the day's work didn't really start until after the morning milking.

It was pretty ludicrous, really, because we, altogether in a day, we spend at least six hours, probably, milking cows.

[upbeat music] Jobs just seem to crop up all the time.

It's a life where you just have to be there all the time and be on call.

And as I say, you never really know quite how your day's gonna turn out.

[upbeat music] [cows mooing] - [Narrator] With the calving season in full swing, Mark also has a nursery to run.

- I know every single cow's name on the place.

I know all their names, and pretty much all their ancestry as well, their history, their mums and dads and granddads.

Once they're born and I've seen them, then that's it, I just know them right the way through.

This is Eclipse.

This is Nonesuch.

Then we have Nelson's Elma.

This is Elma.

She's one of our top show cows.

And here we've got a little small one which was born premature.

She's called Jenny.

And then we've got Marvelous here, who's the youngest.

Marvelous is the latest addition.

[cows mooing] It's not all finished in there.

No, no, no.

There's a side to bring in.

[upbeat music] - [Narrator] In Greek legend, one of the labors of Hercules was to keep a stable clean.

With each of his dairy cows producing 16 tons of dung a year, Mark is only able to keep on top of this superhuman task with a tractor.

[engine rumbling] In addition to mountains of dung, worldwide, cattle are responsible for 12% of all methane gas emissions, contributing significantly to global warming.

- The cows can get a pretty good idea of what mood I'm in.

If I'm not in a particularly good mood, and they can sense it, then they'll start misbehaving.

[upbeat music] Shush!

Oh God.

This is ridiculous.

Go on!

Shh!

Sst!

Come on!

Come here!

Shh!

[cows mooing] It's almost like a human relationship.

I mean, you have kind of a fallout, and then you make it all back up again, and everything's fine.

[whimsical music] [cows mooing] [machinery clanking] [laid-back music] And just by walking and looking at the cows and being with them, you can, without meeting the owner, you can get a pretty good idea of what the owner's like.

So if you get a quiet herd of cows, you'll tend to get nice, quiet human being.

That's all already taken up.

And it's manure, isn't it?

[Mark laughs] Am I buying it off you or off him?

- [Narrator] The moral of Mark's story is simple.

If you want to get a life, don't get a herd of cows.

Mark is all things to his herd, medic, midwife, wet nurse, matchmaker, and leader, and he knows exactly who's boss.

- I have to be honest with you that I am totally in charge of the cows, and the cows are totally in charge of me.

- [Narrator] As a practicing vet, Professor Webster is on a routine visit to Mark's farm.

For Webster, the cow's genius lies in the way it has, since earliest times, done for man what man can't do for himself.

- Our relationship with the cow started in a pastoral era.

And in these circumstances, people were landless.

They didn't own the land, and they couldn't eat grass.

So what the cow did was to go out onto land which they don't own, and eat food which we can't digest, and convert that into, in essence, just about all the necessities of life.

[calm music] - [Narrator] The Ngorongoro Crater in Tanzania is a vast volcanic caldera lying in the heart of the Maasai tribal lands.

[Shangi whistling] This is Shangi, one of the warriors who guards the clan's herds.

Ngorongoro means cowbell, the sound and symbol of man's final dominion over the cow.

The Maasai individually mark their cattle, but according to custom, all cattle belonged to the Maasai anyway, a gift from the great god N'gai at the beginning of time, a belief which justifies the ongoing practice of cattle raiding.

[cowbells clanging] - The cow in traditional societies was probably the most valuable commodity the family had.

The story of "Jack and the Beanstalk."

When Jack sells the family cow for magic beans, the mother is appalled, because you cannot afford to get rid of the cow.

She's the most valuable thing you have.

- [Narrator] With their many biological gifts, cattle rapidly became a form of wealth, their value embedded in our language.

The very word cattle comes from the Old English word for property, and the word spree, as in spending spree, is Scottish for cattle raid.

[tribespeople chattering] Cattle still stand at the heart of the Maasai's economy and their pastoral lives.

Without cattle, Shangi would not even be able to marry.

The 30 or so cattle needed to secure a wife will be the largest outlay of his life.

[cowbells clanging] Shangi brings the clan's cattle down to drink at a waterhole.

As they approach, wild buffalo are forced to move off.

Together, man and cattle rose to the top of the pecking order, and could dominate other species.

Even the surly buffalo must give way to the formidable team.

[cowbells clanging] [cow mooing] At the heart of this bond is the remarkable biology of the cow.

A cow can eat pretty much anything and miraculously transform it into milk, meat, and a whole range of other products that sustain our daily lives.

- The key to the cow's success lies here, the rumen.

It's of the belief of every school child that the cow has four stomachs.

That's not really true.

What it has is one true stomach, the abomasum, which is exactly the same as our stomach.

Upstream of that is a multi-compartment fermentation vat, fermentation chamber, wherein live the microbes.

Now, when the cow goes out to graze, she eats the grass really as quickly as possible, and swallows it almost unchanged.

That comes into the rumen, and at that point, it's really quite difficult for the microbes to penetrate through the cell wall and start the chemical digestion of the plant fiber.

So what the cow has also evolved is this really elegant mechanism of rumination.

In this, she moves the food round in the rumen, and then a bolus of food is regurgitated, passes up to the mouth, and then she takes it in her mouth, and chews it rather as old cowboys would chew tobacco, 20 chews on one side, 20 chew on the other.

This breaks it up, and it comes back down again into the rumen.

The microbes, having done their work, then are passed out of the fermentation chamber, into the abomasum, where they heroically die, and give up their lives to provide protein for the cow to produce milk and meat for ourselves.

- [Narrator] Having given so much, what does the cow get in return?

[tribespeople chattering] Shangi shows a young boy how to use his spear to protect the herd from hostile tribes or predators.

Without their carefully-trained bodyguards, cows wouldn't last long on the open savanna.

[soft, brooding music] [people vocalizing] But the greatest threat the Maasai cattle will face is not from predators but from natural causes.

Drought, and in particular, disease.

At this time of year, the migrating wildebeests pass through the Maasai grazing lands with their young calves, bringing with them malignant catarrhal fever, fatal to cattle.

The Maasai protect their precious herds by taking them up into the hills and away from possible infection.

They invest everything in their cattle, and live primarily off the interest of milk, the most important part of their diet.

A calabash of milk is this boy's main, sometimes only, meal of the day.

Blood is another renewable resource, and the warriors regularly harvest this valuable protein.

When done properly, it causes no long-term harm to the cow.

[tribespeople singing] Meat is reserved only for very special occasions, feasts and celebrations, when the Maasai cash in their precious capital and kill a bull.

Only warriors are allowed to witness the slaughter, which is carried out with skill and respect for the animal.

[hunters speaking in foreign language] - [Narrator] Nothing is wasted, and each part of the animal is ritually shared.

The best cuts are reserved for the elders.

Next, the warriors.

Finally, women and children are served.

[cowbells clanging] The Maasai's intimate relationship with their cattle seems untouched by the passage of time.

But in other societies, the traditions of the past must survive in a radically-changed present.

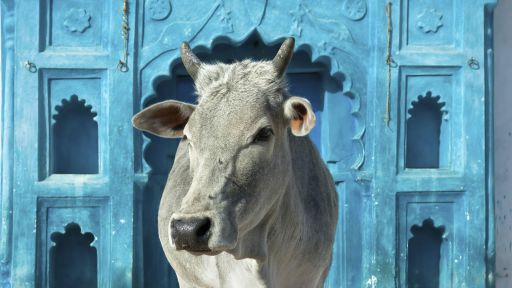

[horns honking] [brooding music] This is downtown India, the original land of the holy cow, with the largest national population of cattle in the world, 250 million of them.

Many of India's cattle are born, will live, and die here in the cities, sleeping rough in the streets, never seeing green fields.

Taking each day as it comes, urban zebu, the ancient humped cattle of India, have adapted to graze not on grass but on garbage, making do on a diet of discarded fruit and vegetable waste, or if need be, newspapers and cardboard boxes.

Once again, the cow's miraculous stomach comes to its rescue.

With the help of the trillions of bacteria and billions more protozoa resident inside the 50-gallon rumen, the cow is able to ferment otherwise indigestible cellulose into vinegar, its primary source of energy.

Just another everyday miracle in the life of the holy cow.

But occasionally, even this ultimate survivor falls on such hard times that it needs our help.

[mysterious music] Enter Dr. Sardana Rao, who retired from medical practice to devote her whole life to the welfare of old and injured cattle.

[mysterious music continues] She is the Mother Teresa of the bovine world, funding this hospice from her pension and whatever donations she receives.

- This place is actually a home for the abandoned, unwanted, old animals, mostly cows.

I accept destitute, abandoned, sick, lame, blind, all animals.

This one is completely blind.

It was born blind.

His name is Gopi.

This fellow is Gopi.

[cows mooing] She's 23 years old.

In this herd, she's the oldest cow.

I once had a cow which is 26 year old.

There are no teeth there.

We have to cut the grass.

We have to give her only the softest things.

- [Narrator] Some of Dr. Rao's charges have endured terrible suffering.

These buffalo were caught in a fire in their stable, and were rescued by Dr. Rao.

That was three years ago, and she's still nursing them back to health.

- This one goes on licking.

It doesn't tell me to do anything.

Okay, okay, man.

Okay, man.

You have to talk to them to make them feel at home, so that even when they're in pain, even when they're in pain, if you are near them, and if you talk to them, they get a kind of moral support, and they're able to bear the pain.

I cannot bear when they are unhappy.

And I feel like fish out of water when I'm not in the midst of cows.

[bright, mysterious music] - [Narrator] Dr. Rao knows each of her charges as an individual.

- His name is Ayopasami.

Ayopa for short.

[bright, mysterious music continues] I feel very happy when I'm with them.

Completely fulfilled.

- [Narrator] What motivates someone to dedicate their whole life to the welfare of cows?

- God has sent me in this world only to serve them.

That's what I think.

I have no other explanation.

- [Narrator] The cow occupies a unique place in the religious life of India, where cattle are considered sacred.

The divine bull Nandhi guards Hindu temples, while the holy cow Karmadenu grants all human wishes.

Together, they and their living incarnations are worshiped by 750 million Hindus.

[priest chanting in foreign language] [bright, mysterious music] - [Narrator] As night falls, a cow goes into labor.

It is a familiar nativity scene In tens of thousands of stables up and down this vast land.

[bright, mysterious music] Just after midnight, her waters break.

In the early hours, a calf is born.

[rooster crowing] [cow mooing] But this is no ordinary morning, and therefore, this will be no ordinary calf, for today is Mattu Pongal, India's bovine thanksgiving, when the cow's many gifts are celebrated.

[water splashing] [people yelling] Mattu Pongal begins at first light.

After the farmers have washed their herds, the cattle are decorated, and then fed ritually-prepared food.

[upbeat music] On Mattu Pongal, even street cattle help themselves freely from the local vegetable markets.

[upbeat music continues] For the street cows, today is a day of abundance in an otherwise tough existence.

But our special calf is destined for a very different life at the local temple.

The calf's auspicious birthday ensures its privileged future.

[bright music] Its short journey will pass through thousands of years of living history.

[bright music continues] [people chattering] [rooster crowing] Contradictions are the foundation of everyday life here.

[priest chanting] Revered as sacred, the cow is also a lowly beast of burden that toils in the fields and provides daily transport.

[priest chanting] Hand fed, pampered, and decorated, the cow is also abandoned to forage for itself in the streets.

[cow mooing] The cow is both a long-suffering animal and the infinitely-adaptable mother of the universe.

[cow mooing] Even in the 21st century, a new building cannot begin without the holy cow's blessing, and when complete, the owners must perform the necessary bovine rituals.

[priest chanting] This is no backward village superstition.

Attending this ceremony are modern professionals, a filmmaker, a doctor, an airline pilot, and a successful businessman.

But without the cow's blessings, nobody can move in.

[upbeat music] If to westernize India seems a riddle, then the holy cow is surely hers sphinx.

[mysterious music] The calf's journey ends at the temple.

[mysterious music continues] Within the Goshala, the sacred stable, the calf will live out its life alongside other resident holy cows, acting as a focus of thanks for the many gifts which the cow has given to India.

[mysterious music continues] [bell tolling] [cows mooing] Cattle reflect the values of the cultures to which they belong.

And in the west, the cow has adapted to suit the needs of a more secular society.

In the rolling countryside of England, the cow would perform its most practical conjuring trick, literally changing shape to suit its master.

Although different types of cattle evolved in different parts of the world, it was in England in the 18th century that the story of cattle breeding really began.

The names of British breeds record where they originated in the United Kingdom.

And although a small island, the result has been over 40 different shapes and sizes.

[upbeat music] This is the English Longhorn, one of the oldest recognized breeds in the world, and the first bred purely for beef.

The Highland, a hardy breed from Scotland, able to endure the most extreme conditions.

The Gloucester, an early dairy breed, celebrated for producing cheese.

Aberdeen Angus, renowned for meat production, and the most popular beef breed in America today.

The South Devon, the largest British breed.

And finally, the Hereford, the most widespread and adaptable of all cattle.

[upbeat music continues] At Haven Farm in the heart of Herefordshire, the Lewis family have been successfully breeding pedigree Herefords for over 100 years.

The first Hereford came from a farm a few miles down the road, and today there are 30 million of them from Alaska to New Zealand.

[bright music] Edward Lewis prepares to load two prize bulls, Volcano and Viking, for the annual pilgrimage to the Three Counties Agricultural Show at Malvern.

Success in the competition brings far more than just a winner's red rosette.

Artificial insemination means that a champion can fertilize tens of thousands of cows in a lifetime.

The very top pedigree bulls can earn their owners $1.5 million in stud fees a year.

At the Malvern Showground, Edward Lewis's stockman settles in the bulls.

Edward's son Ben will be the sixth generation to breed Herefords, following his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather, [bull mooing] in an unbroken line back to Thomas Lewis, the founder of the herd.

- The family's been involved since 1822.

So yeah, it's long enough.

[laughs] - [Narrator] The final washing, drying, and brushing by the Lewis girls are just the last-minute touches on years of preparation, with decades of selection and breeding going into the presentation of the top pedigree animal.

- Well, there's a lot of work gone into them, and its sort of now or never.

But at the end of the day, we're pleased with the way they look, anyway.

[cattle mooing] - [Narrator] First, the judge looks at the animal's locomotion, its general structure, color, and markings.

Next, he assesses the combination of straight back, the set of the shoulders, well-made hindquarters, and correct placing of the feet.

[cattle mooing] Finally, it's the overall size and the balance of muscle to fat that will determine meat production and decide the choice of champion.

[cattle mooing] But the coveted red rosette goes to a rival.

Edward comes in a respectable second with a blue.

Although today is not the Lewises' day, they are sure to produce more champions.

The Haven Farm has held the British sale record for the past 20 years.

[bright music] Different cattle breeds reflect a combination of where they came from and what they are intended for.

By exaggerating desirable characteristics through careful selection, man has created 800 different breeds, with shapes and sizes never before seen in nature.

- In the gentle plains of Southern England, or on the Great Plains of the States, the beef cattle have been selected by man to produce beef.

That's to say, they have short legs and vast amounts of meat all around them.

So they've been selected by the butcher, in essence.

- [Announcer] The winner of the [indistinct] trophy is the British Simmental champion, Sterling Crackerjack.

[upbeat music] Boddington Estates, Cheltenham in Gloucester.

- Thank you very much indeed.

- That's a wonderful animal.

- Thank you very much indeed.

- Well shown.

Thank you very much.

- [Announcer] He's nearly 1,600 kilos in weight.

- [Narrator] Beef is only half the story, and now it's the turn of the dairy cattle at the Malvern Show.

Exhibiting his classic black and white Holstein Friesians is dairyman David Kale with his daughter, Emma.

What qualities will the judges be looking for this time?

- They've got great udders on them, is what he's gonna be looking for.

The teats are the right place.

The leg set is right.

The openness of rib is right.

The dairyness through the front end is right.

The skin is even right.

It's just what I think the modern-day Holstein breeder would thrive to try and breed though, ideally.

You have to try and figure out what time the cow's gonna look her best.

They were milked at four o'clock last night, so we believe that they're capable of carrying 17, 18 hours of milk to look their real best.

'Cause at the end of the day, if we don't get those udders blooming like they should, and we don't get that udder filled right to the top, she won't win her class.

- In a dairy cow such as this, this is the factory.

This is the udder where the milk is produced.

In an Ayrshire cow, in a very natural grazing environment such as this, will at peak give about 50 or 60 pints a day, which is about 12,000 pints in a lactation.

And it is secreted in cells that live in the top part of the udder.

Underneath that is a cistern, which is as the name implies.

It's just a tank that holds the milk.

At the bottom of that, we have the teat and the teat canal, which remains closed, for obvious reasons, until such time as either the calf comes to drink from its mother or she goes into the milking parlor.

Then a hormone, oxytocin, is released from the brain, it's carried in the bloodstream to the secretory cells of the udder, and causes myoepithelial, specialized cells, to contract and squeeze the milk out of the secretory glands, into the cistern, and out through the teat canal.

- [Narrator] In the dairy breeds, milk production is what counts.

- Worthy winners of the last class.

- Thank you very much.

- [Narrator] David Kale has timed it perfectly, and with magnificently blooming udders, his prize cow has swept the opposition from the field.

[bottles clanking] In the last 50 years, genetics and breeding have tripled the average dairy cow's milk production.

A Wisconsin Holstein called Miranda Oscar Lucinda produced nearly 68,000 pounds of milk in one 12-month period, enough for 650 bowls of cereal a day.

The dairy business in America alone is worth an estimated $75 billion a year.

The colossal increase of dairy production has been matched by an equally dramatic increase in beef production.

Eric Schlosser is the author of "Fast Food Nation," a controversial overview of America's eating habits in the 20th century.

- The slaughterhouses of Chicago at the turn of the century were what inspired Henry Ford to create an assembly line system for the automobile.

So the assembly line, really, as an idea in America begins in the slaughterhouses, except, they are disassembly lines.

So a steer will walk into the building, completely unaware of what comes next, maybe thinking that he's about to get on another truck to go on another trip, and is suddenly stopped by a barrier.

[suspenseful music] And at that point, someone shoots the steer in the head.

This employee is called the knocker, who is literally knocking the steer unconscious.

And then a chain is put around one of the hind legs of the steer, and the steer is suddenly lifted up in the air, at which point a sticker with a long knife will slice the artery in the neck, and the animal then bleeds to death.

What's extraordinary about American slaughterhouses is the speed of production.

300, 350, 400 cattle an hour sometime, down this one line, and the workers are working at an incredible pace to keep up.

It's almost like something out of the Charlie Chaplain film, "Modern Times," of workers being completely obedient to the production line or the machinery, and the cattle just never stop coming.

[suspenseful music continues] [brooding music] - [Narrator] And this is where most cattle come from, feedlots like this one in Colorado, where steers are fattened on grain before being slaughtered.

This facility can house up to 120,000 animals.

The beef from an average steer sells for around $1,900.

When full, this feedlot holds over $230 million of retail product.

- Our food production has changed more in the last 40 years than in the previous 40,000 through the industrialization, in particular, of livestock, of cattle.

Cattle were being raised in the United States up until recently as they'd been raised for millennia, essentially eating grasses out on the prairie.

And it's in the last 40 to 50 years that a feedlot system arose in which cattle were being fed grain, and in particular, corn.

And it's in the last 25 or 30 years that we've had this intense industrialization of cattle.

- [Narrator] The cow's miraculous stomach can cope with almost anything, but the feedlot diet of corn, while extremely fattening, also makes the animals vulnerable to disease.

The cow's rumen can become inflamed, and bacterial infections can spread through the damaged stomach wall, causing anything from liver abscesses to brain damage.

To fight off infection, an estimated 3.7 million pounds of antibiotics are fed to cattle each year in America, almost 1 million pounds more than are given to sick humans.

- In order to have 100,000 cattle penned up in one space, you have to manage them differently.

You have to raise them differently.

Antibiotics become crucial to prevent large-scale outbreaks of animal disease.

If you look at how cattle live and eat in America now, for the most part, it's been completely revolutionized, and there's nowhere else in the world that's raising cattle this way.

- Industrialized agriculture is really something that's very new.

It happened in the last 50 years when energy costs became cheap.

We could take the animals off the land, we could bring the food to them by machine, and we could take away the dung by machine.

It also became possible with the use of antibiotics, which meant we could keep large numbers of animals together without killing the lot.

Now, both of those things are gonna break down sooner or later.

The cheap energy isn't gonna work, so it's gonna be cheaper for the cow to go out and find her own food, which was always a strength.

And the maintaining of animals in very intensive conditions under blanket antibiotic cover isn't gonna work either.

In fact, is dying soon.

So this extreme intensification of agriculture in the last 50 years is probably something of a blip in the whole evolution of man's association with animals.

- [Cowherd] Hey!

Hey!

- [Narrator] There is a new breed of ranchers across the United States raising cattle in a very different way from the feedlot system.

One of them is Dale Lasater, who runs the family ranch in Matheson, Colorado.

Dale brings the story of man and cattle full circle.

[calm music] [cow mooing] - On both sides of my family, my mother's family, my father's family, We've been involved in raising cattle in the American West since the 1850s.

I think having been involved with cattle and land for that period of time helps give one a longer-term perspective and helps understand that the natural world moves slowly, both in being degraded and improving.

- [Narrator] The Lasater philosophy is to recreate as natural a set of conditions as possible.

This means starting literally at grassroots, trying to restore the prairie that once fed vast herds of migrating bison.

[cow mooing] [bright music] Miles of fences crisscross the Lasater Ranch as part of a grass management system designed to prevent overgrazing.

- Much of this approach to grazing and handling our cattle on these pastures is an attempt to mimic the migrating herds of the past that were on the Great Plains, such as the bison.

Since we have fences and we've contained the cattle, we have to mimic that by moving them, again, by trying to plan the grazing so that we don't come back until all plants have been recovered.

- [Narrator] Foreman Eddie Stanko places great value on building trust between man and cow.

- The first thing that we do different is, nobody else that I know of gentles their cattle like we do.

When we wean our calves, we go through the gentling process, which calms them down and teaches them all to eat cake out of your hand.

As compared to the neighbors, you drive by the fence, and the cattle are taking off over the hill, instead of standing still and letting you do whatever you want to.

Come calving time, it's really, really important, 'cause you don't have to worry about the cow taking off over the hill while you're trying to catch a calf.

And that's one of the things that we... Nobody else that I know of does that.

- [Narrator] The Lasaters don't use pesticides.

And although they don't have large predators, which other ranchers face, there's no shooting of coyotes or other so-called pests, either.

Dale leaves the welfare of his 1,500 cattle to the prairie, on which they will spend their whole lives.

[cow mooing] - The more one knows about the natural world, and the longer a person spends in the natural world, such as the short grass prairie where we are here, the true miracle of what is happening here is quite astounding.

Our role here as land managers, cattle managers, is simply to stay out of the way enough that the natural forces can come into play, and maintain and sustain this tremendous resource, which really requires very little input from us, except hopefully not doing the wrong thing.

- A lot of people, they get shook up about things, and if they just sit still and let Mother Nature take its course sometimes, it's better off than trying to hurry things.

- [Narrator] But can places like the Lasater Ranch provide a realistic solution to our insatiable demands for meat in the 21st century?

Professor John Webster.

- Dale Lasater's ranch is a utopia for beef cows.

He has a market for this very high quality product.

It is the Rolls Royce of beef production, and there are people who are prepared to buy that.

But it will never replace the feedlot absolutely for the simple reason that not everybody can afford a Rolls Royce.

I'm sure that we will continue to have for urban societies quite a lot of industrial production.

But I think, inevitably, in time, there will be a step back, not to the past, but to a more ecologically sound, more humane system that fully recognizes the value of the land and the value of the cow.

[bright music] - There's no question that Dale Lasater represents the latest evolution of man's relationship to cattle.

And I think that what the Maasai do with their animals and how they treat their animals is very much analogous in an American context to Dale Lasater and his practices.

[bright music continues] - [Narrator] The Maasai might seem unconnected to the world of modern farming practices, but this is where our story began, and this is where it now returns.

[bright music continues] For 8,000 years, all over the world, humanity has been bound by our common dependence on the cow.

[people singing] For the Maasai, giving cattle to a neighbor in need is the ultimate expression of sympathy and friendship.

[people singing] [tribesperson speaking in foreign language] - [Narrator] Although apparently a world away, the news of the 9/11 attack on the Twin Towers soon carried to the distant pastures and campfires of the Maasai.

The unimaginable events were carefully described.

[tribesperson speaking in foreign language] - [Narrator] On hearing of the tragedy, one Maasai tribe was moved to give cattle, the most valuable thing they own, to the people of New York.

[somber music] The cow carried a message of condolence from one tribe to heal another.

[somber music continues] [bright, calm music] Some would argue that we did not domesticate the cow, the cow domesticated us.

Whatever the truth, this creature's many gifts have sustained the human race on our journey to civilization, and each of us continues to owe a daily debt to the humble, extraordinary cow.

- [Announcer] This program was made possible by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

[dramatic music] [bright music]