As a skier and martial artist, Arnaud Eboli showed discipline, grace, and considerable athletic skill. So his family was mystified, then horrified, when the French teenager began exhibiting fits of rage and then started stumbling around his home in the late 1990s. Soon, he couldn’t remember things and his speech began to falter.

“It was as if his mouth was full of food and he couldn’t push the words out,” his mother told reporters. In April 2001, Eboli died — paralyzed and comatose — becoming one of the world’s roughly 150 known victims of “mad cow disease.”

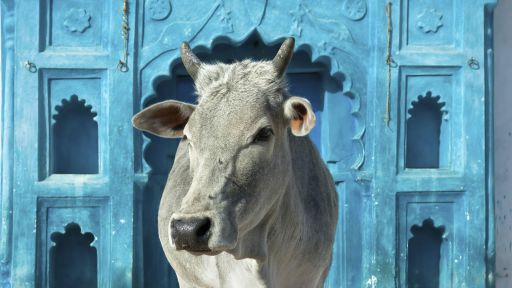

First recognized in the United Kingdom in the 1980s, mad cow disease — formally known as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) — causes the brains of cattle to waste and become spongy and pockmarked. (A similar disease, scrapie, has been known to affect sheep for more than a century.) Stricken animals stagger and behave erratically — like “mad cows” — and eventually are unable to stand. Although BSE was recognized as a problem for farmers, it took a while for officials to realize that the disease might threaten people who ate beef, too. Only in the last decade have researchers been able to piece together much of the sobering story.

Today, scientists believe mad cow gained its foothold in the U.K. when farmers began giving their cattle feed which was laced with tissue from other farm animals, that included sheep and “downer” cattle. The tissue held hardy, misshapen proteins — called prions — that are believed to cause the disease by triggering changes in normal proteins. These prions can be transferred to people when they eat beef products that include infected brain, spinal cord, or intestinal tissue.

In infected people, the prions cause what doctors call “variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease” (CJD) — the disease that killed Arnaud Eboli. It can take years for the disorder to fully develop and, so far, there is no known cure. In Britain, more than 140 deaths have been attributed to the disease. The first known human victim was Stephen Churchill, 19, who died in 1995.

Once the deadly chain was understood, first Britain and then other nations took drastic steps to stop the spread of mad cow. In the United Kingdom alone, almost four million cows suspected of carrying the disease were destroyed. Governments banned the sale of feed including tissues from other livestock. Many nations began testing programs, although the only certain way to know if a cow is infected is to study its brain after it dies.

So far, such steps have prevented other major outbreaks. But concern remains high. When the United States discovered a single infected cow in late 2003, for instance, there were profound repercussions. The discovery prompted a steep drop in beef prices, a ban on U.S. exports, and a nationwide search for other infected animals. Hundreds of animals were slaughtered in a bid to head off any potential outbreak.

Researchers continue to try to understand mad cow and invent better ways to detect it. The February 2004 announcement of a new strain of the disease, found in two Italian cows, may prompt the Department of Agriculture to adopt more sensitive tests already used in Europe. In the meantime, researchers warn that everyone from farmers to consumers need to keep a watchful eye on what they eat — and what it, in turn, was fed.