All images courtesy of Philmont Museum – Seton Memorial Library

Cimarron, New Mexico

A gift of Mrs. Julia M. Seton

Lobo After His Capture

Lobo After His Capture

The image is a photograph that Seton took of Lobo after his capture near the headquarters of the L Cross F Ranch which belonged to Louis Fitz-Rudolph. The photograph details the stark landscape in which the wolf met his demise, as well as the ensnared wolf cowering away from the Seton as he shot the photograph. This is the image that would remain with Seton long after the event.

Publicity Shot of Ernest Thompson Seton

Publicity Shot of Ernest Thompson Seton

Publicity photograph of Ernest Thompson Seton at the peak of his career taken in New York in 1906.

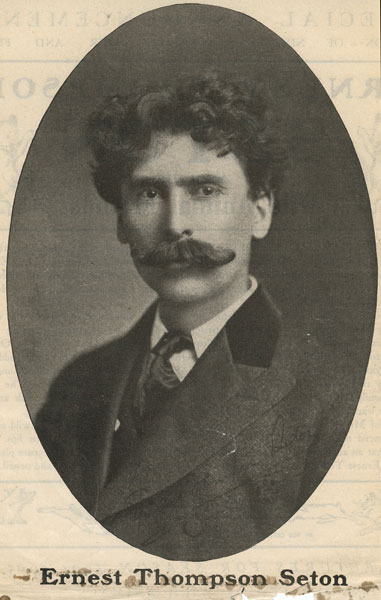

E.T. Seton, Lecturer

E.T. Seton, Lecturer

Publicity photo of Seton advertising his lecture series.

“The Black Wolf of the Currumpaw”

“The Black Wolf of the Currumpaw”

“The Black Wolf of the Currumpaw” oil painting (1894). One of the most detailed and captivating oil paintings produced by Seton shortly after Lobo was trapped on January 31, 1894. The detail Seton put into this painting exemplifies Seton’s interest in Lobo. This image would appear on the cover of The World of Ernest Thompson Seton, edited by John G. Samson and published by Alfred A. Knopf in New York, 1976.

Early Cover of Wild Animals I Have Known

Early Cover of Wild Animals I Have Known

An early cover of Wild Animals I Have Known, in which Seton included the story of Lobo. The story marked the beginning of a new writing style for Seton, in which he began to abandon his use of applying anthropomorphic qualities to the animals of his stories.

Blanca, Lobo’s Mate

Blanca, Lobo’s Mate

A photograph of Blanca, Lobo’s mate (1894).

“Within a mile or so, we came up, and found that the little wolf in the trap was Blanca safe and sure. Lobo was with her running alongside. He would not leave her. But when he saw the men coming with guns, he knew he was powerless. He called her to follow, and led up the side of the hill to the mesa. She did follow for a time, until the horns of the big beef head caught in the rocks and held her. Then she had to turn and face us.

“Just then, up came the sun, and shone full on her. I saw now what a beautiful creature she was – pure white. I used my camera, and made the lasting record given.” (Trail of an Artist-Naturalist – the autobiography of Ernest Thompson Seton; pg 336, Charles Scribner’s Sons, NY 1941).

The two photographs of Lobo and Blanca were later used by Seton to symbolize the extermination of wolves from the southern plains. It was this event in which Seton began to realize he had killed “his kindred” in cold blood.

“Lobo and Blanca”

“Lobo and Blanca”

Pen and ink with tempera (1894).

“Wolf Study”

“Wolf Study”

Pen and ink with water color (1896).

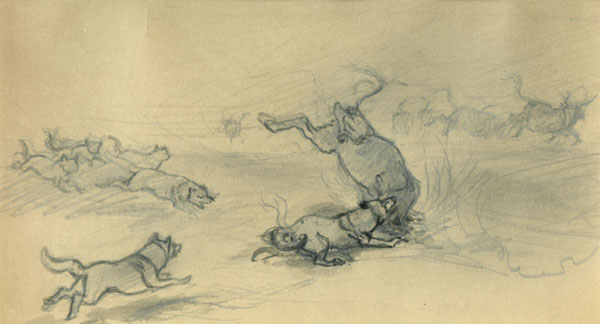

“The Kill”

“The Kill”

Pen and ink (1893). The observed New Mexico wolf pack attacking a cow.

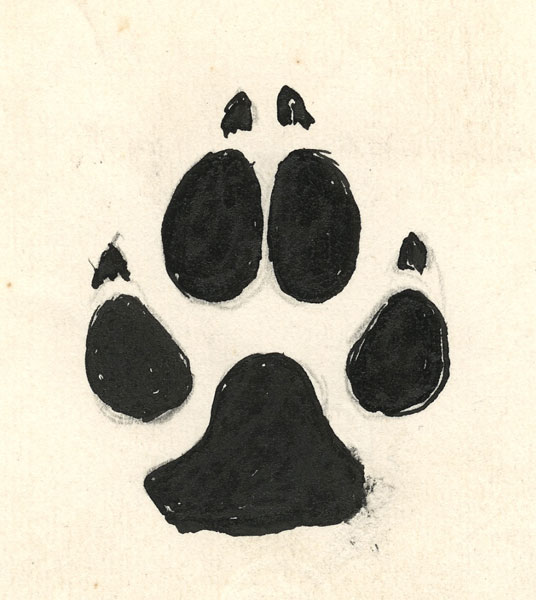

“Wolf Track”

“Wolf Track”

Pen and ink (date unknown). The wolf paw would eventually become incorporated into Seton’s signature to express his symbolic kinship to the wolf.

“The Persuit (La Poursuite)”

“The Persuit (La Poursuite)”

Oil (1895). In his autobiography, Seton said that he painted this large oil trying to imagine how a pack of wolves would look from the rear of a speeding Russian trapper’s sleigh. The painting was begun in 1894. The scene was derived from a story he later published in Forest and Stream titled, “The Baron and the Wolves.” Although the painting’s meaning is ambiguous, one scholar has postulated that Seton “meant to show wicked men pursued by vengeful wolves retaliating against man’s destruction of nature.”

Several preliminary sketches, wolf studies, and color schemes were used in preparing for this painting. After its completion in January 1895, it was submitted for hanging in the Grand Salon of Paris. The painting was rejected, perhaps because the message was not easily understood. Nevertheless, several of the preliminary studies were accepted and displayed.

President Theodore Roosevelt, a friend of Seton’s, was impressed with the painting. He commissioned Seton to paint a canvas of the lead wolf. The resulting painting hung in the Roosevelt Gallery for many years. It was also used as the frontispiece of Volume II or Seton’s Life Histories of Northern Animals.