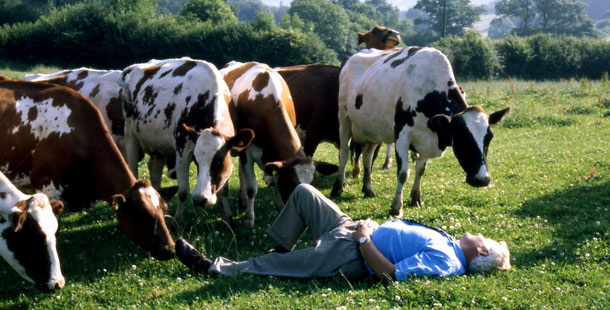

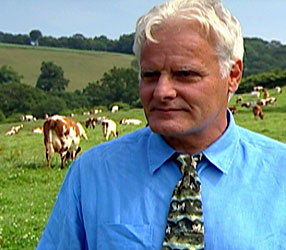

In NATURE’s Holy Cow, viewers meet John Webster, a British expert on cattle and animal welfare. Webster, a former president of the British Society for Animal Science, was one of the researchers asked by the British government to study the causes and consequences of mad cow disease. In 2004, NATURE spoke with Webster about the past, present, and future of cows from his home, which overlooks one of England’s many dairy farms.

In Holy Cow, the Lasater Ranch is used as an example of a more ecologically sustainable and more humane way to raise cattle. Is it the wave of the future?

Well, the Lasater Ranch is producing the equivalent of Fabergé eggs — a very high quality product for which people are willing to pay something extra. But it’s not as different from the usual practices as it may look. The major difference comes in the last 150 days of the calf’s life; instead of being intensively fed corn and grain, Lasater Ranch calves feed on the range.

The typical method of raising beef in the United States probably will continue to spread to other parts of the world, in areas where it makes sense: where the breeding cows can get most of their food out on the open range, and the calves to be slaughtered spend the last part of the cycle being intensively fattened. Often, it’s the best use of the land. It’s a very effective way of transforming plants we don’t eat into something we do like to eat. I’m not saying it’s the most admirable method, but that it works very well and is likely to continue.

In general, where do you see cattle operations headed?

Due to concerns about mad cow disease and animal welfare, I think there will be an increasing trend toward marketing steaks so that [the consumer] knows exactly which farm or farmer they came from. Some sources will be perceived to have higher quality.

As far as the welfare issue is concerned, however, the problems with beef cattle are nothing compared to the problems in the dairy industry. So anyone who avoids beef and elects to eat cheese due to welfare concerns is missing the point.

Where would you like to see things headed?

I’m not too concerned about beef, but the dairy industry is a big concern. In dairy, I believe the industry needs to “redesign” the cow. The approach with American Holstein dairy cows has just gone too far. The cows are very productive, and the system looks cost effective in the short run, but it uses the cows up way too quickly. On strictly economic grounds, cows should be lasting at least four lactation cycles, but it takes just two or two and a half cycles to use up current cows. An awful lot of cows are culled after that.

And it’s not just me crying wolf — the industry has realized things have gone too far. They are looking at changing the way cows are selected, trying to maintain milk production without getting a bigger and bigger cow that can’t hold herself on her feet. It’s a real shame to see these young animals glowing in good health, and then seeing them turn into old crones within a year.

What do we know now about the origins of mad cow disease, and ways to prevent it?

I was on a committee here in the U.K. that studied the issue, and nobody really knows the origins for certain. It may have always been with us at a very low level, people just didn’t notice. But our farming practices multiplied it, particularly by giving young cows feed that included infected material, such as bone meal, from other cows. Studies show the vast majority of our cows were infected as young animals from material that was in their starter rations. That was pretty much unique to the U.K., and probably why we had a bigger problem than the rest of Europe. But if it is true that mad cow has always been here, it may never go away completely.

Are there still major differences in the way cows are raised in the U.S. and Europe?

Fewer and fewer. Traditionally, in Europe the cow took most of its food off the land. But it is becoming a lot more like the U.S., with grain coming in at the end of the cycle for beef cattle.

Have we reached the end of the road in cattle breeding, or will new engineering technologies produce new “super cows?”

Well, it depends on whether you are talking about beef or dairy. We’ve discussed dairy. In beef, however, you are really selecting for different things in the animals you are going to slaughter for meat, and the animals you are going to use for breeding. The best cow is not the best slaughter calf. In the calves you want muscle, and you want them to get large. The cows need to stay fat over the winters. So anyone who thinks you can breed one perfect cow for everything is headed in the wrong direction.

The cow has become a cultural icon in the United States. Companies put it on their products, and cow memorabilia is a huge craze. What accounts for that?

You know, the great thing about the cow is that she can eat plants we don’t, on land the farmer might not own, and convert milk into cash for the farmer. So a cow was often the most valuable thing a farmer owned. Even during a drought, they would hold some value. So cows became an icon for value; they were simply the most valuable animal around. And in modern times, there is still the image of the cow as a rural animal, a symbol of what the poet Blake called “the green and pleasant land” of England where we built our “Jerusalem.”